41,000 Years Ago, Earth Lost Its Magnetic Shield—Here’s What Happened

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

41,000 Years Ago, Earth Lost Its Magnetic Shield—Here’s What Happened

Scientists have long known that Earth’s magnetic field has not been a constant shield. New interdisciplinary research shows that a major geomagnetic event, the Laschamps Excursion, may have directly impacted human behavior over 41,000 years ago. The study links the sudden weakening of Earth’s magnetic field to an increased exposure to solar and cosmic radiation, leading to striking auroras. The evidence? A marked increase in cave habitation, more complex clothing adaptations, and extensive use of ochre. This paints a new picture of early Homo sapiens as resilient survivors of a planetary space weather crisis. Understanding how early humans responded to solar threats can help frame strategies for future scenarios. The Laschamp Excursion may have acted as a stress multiplier, exacerbating existing challenges and rewarding adaptability. It opens the door to a deeper question: Did space weather help tilt the evolutionary scale? The archaeological record suggests Homo sapien showed more flexibility in environmental adaptation, relying on cultural innovation and material culture.

The Laschamps Excursion: When the Magnetic Field Almost Vanished

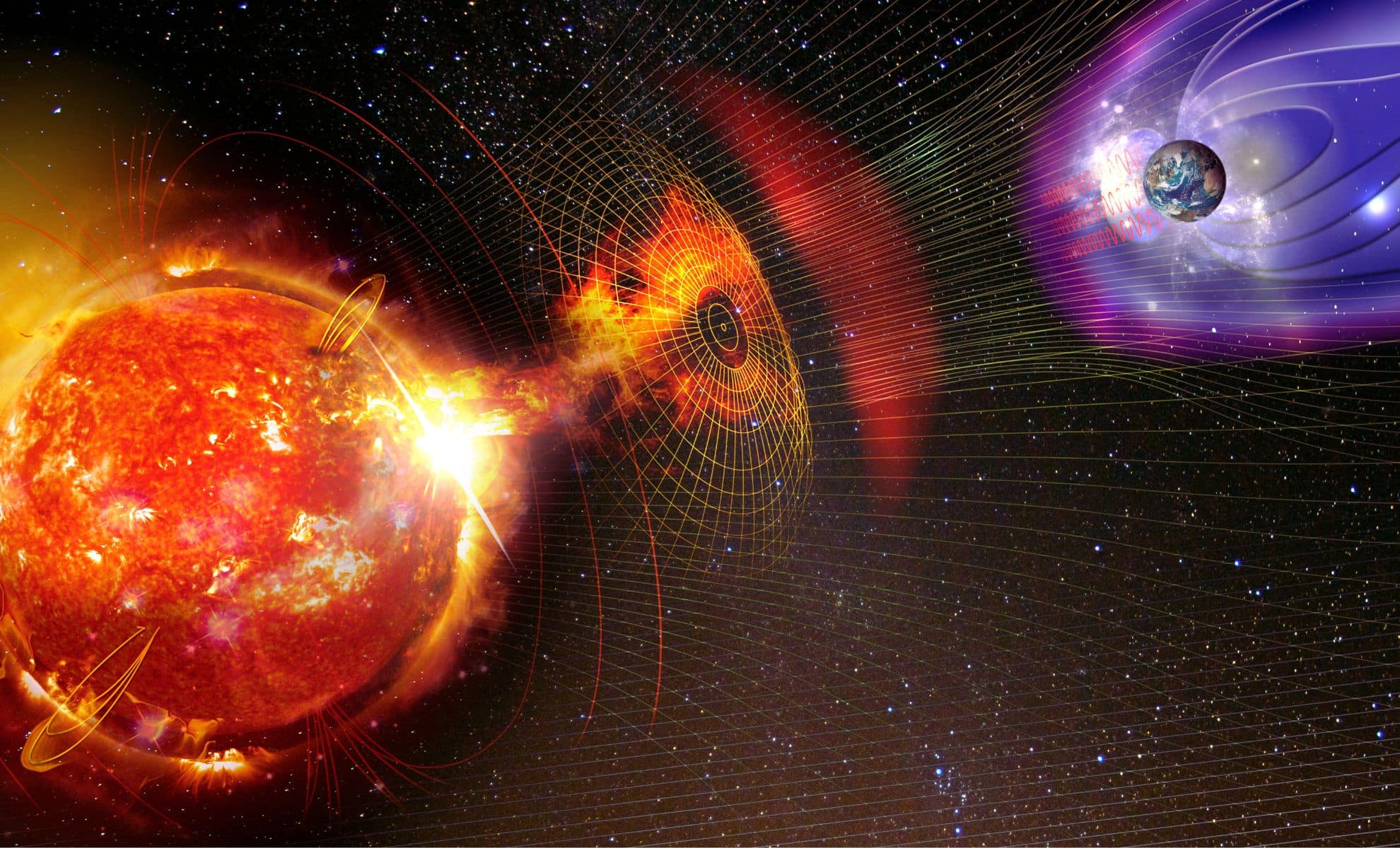

About 41,000 years ago, Earth experienced what is now known as the Laschamps Excursion—a temporary geomagnetic anomaly first discovered in volcanic rocks from France. During this period, the planet’s magnetic field lost up to 90% of its intensity, leaving the atmosphere largely exposed to solar winds and cosmic radiation. Unlike the full pole reversals that occur every few hundred thousand years, this event was a dipole collapse. Instead of having two stable poles, the magnetic field fractured into multiple weak mini-poles scattered across the globe.

The breakdown of the magnetosphere meant that solar particles, typically deflected by Earth’s field, began bombarding the surface at unprecedented levels. These conditions triggered dazzling auroras—likely visible far from polar regions—and exposed life to higher levels of ultraviolet radiation. While these environmental effects are modeled from paleomagnetic and cosmogenic isotope data, the real leap forward comes from connecting these cosmic phenomena to the archaeological record.

Archaeological Clues in the Caves of Europe

The cross-disciplinary team—comprising archaeologists and geophysicists—looked for behavioral changes in prehistoric humans and Neanderthals that might align with the timeline of the Laschamps Excursion. They focused on European populations, where geomagnetic weakening would have had especially strong effects. The evidence? A marked increase in cave habitation, more complex clothing adaptations, and extensive use of ochre.

Caves, naturally shielded from UV rays, likely became safe havens. At the same time, archaeological layers show greater use of tailored clothing—fitting garments made from animal hides, stitched with bone needles. This shift suggests humans were adapting to radiation stress by covering exposed skin, a behavior mirrored in the apparent cosmetic use of ochre, possibly as an early form of sunscreen.

Although direct proof of radiation-driven behavior is elusive, the convergence of timing, geographic distribution, and adaptive responses suggests a causal link. This paints a new picture of early Homo sapiens—not just as clever tool users, but as resilient survivors of a planetary space weather crisis.

Shared Skies, Different Fates: Humans and Neanderthals

At the time of the Laschamps Excursion, modern humans and Neanderthals coexisted across parts of Europe. Their survival strategies in the face of this environmental stressor may have diverged. While the study does not claim that magnetic field collapse directly caused Neanderthal extinction, it opens the door to a deeper question: Did space weather help tilt the evolutionary scale?

The archaeological record suggests Homo sapiens showed more flexibility in environmental adaptation, relying on cultural innovation, material culture, and cooperative behavior to mitigate changing conditions. In contrast, Neanderthals may have had a narrower ecological range, making them more vulnerable to subtle but sustained environmental disruptions like increased UV exposure.

This framework doesn’t suggest a single catastrophic event but rather a pressure-cooker environment in which radiation, climate variability, and inter-group competition combined to reshape human evolution. The Laschamps Excursion may have acted as a stress multiplier, exacerbating existing challenges and rewarding adaptability.

Rewriting Human-environment History Through Space Weather

What makes this study remarkable is its interdisciplinary approach. Archaeologists typically reconstruct past environments through proxies like pollen or isotope data, while geophysicists use models to simulate changes in Earth’s magnetic field. Rarely do the two fields intersect. This collaboration shows that geomagnetic instability—once considered only a planetary-scale concern—can be explored as a driver of human behavior.

Moreover, the implications stretch beyond the past. Understanding how ancient populations adapted to space weather offers insight into modern vulnerabilities. Today’s dependence on satellites, power grids, and electronic systems makes us more, not less, vulnerable to geomagnetic disturbances. Studying how early humans responded to solar threats can help frame resilience strategies for future scenarios.

Source: https://dailygalaxy.com/2025/07/41000-years-ago-earth-lost-magnetic-shield/