Camp Mystic Cabins Stood in an ‘Extremely Hazardous’ Floodway

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Camp Mystic Cabins Stood in an ‘Extremely Hazardous’ Floodway

Camp Mystic pursued an expansion project six years ago. Instead of relocating cabins to higher ground, it put new ones in the flood zone. The cabins were so close to the river’s edge that they were considered part of the “floodway” Many states and counties ban or severely restrict construction in river floodways. In the early morning hours of July 4, the cabins at Camp Mystic were packed with hundreds of sleeping campers. The raging waters tossed mattresses like doll beds, ripping stuffed animals from their owners and ending the lives of some two dozen girls. The New York Times analyzed federal data to identify 19 cabins that were located in designated flood zones, including some in an area the county had deemed “extremely hazardous” The camp passed a state inspection just two days before the flood, with inspectors noting that the emergency plans were not detailed in their report alongside their evacuation plans. The camp was first established in 1926, but as flood data and modeling has improved in recent years, governments have debated how to best manage people who live, work and play along rivers.

For decades, girls have flocked to Camp Mystic to spend their summer days canoeing and fishing the Guadalupe River before retreating to bunk beds in rustic cabins just steps from the glimmering water.

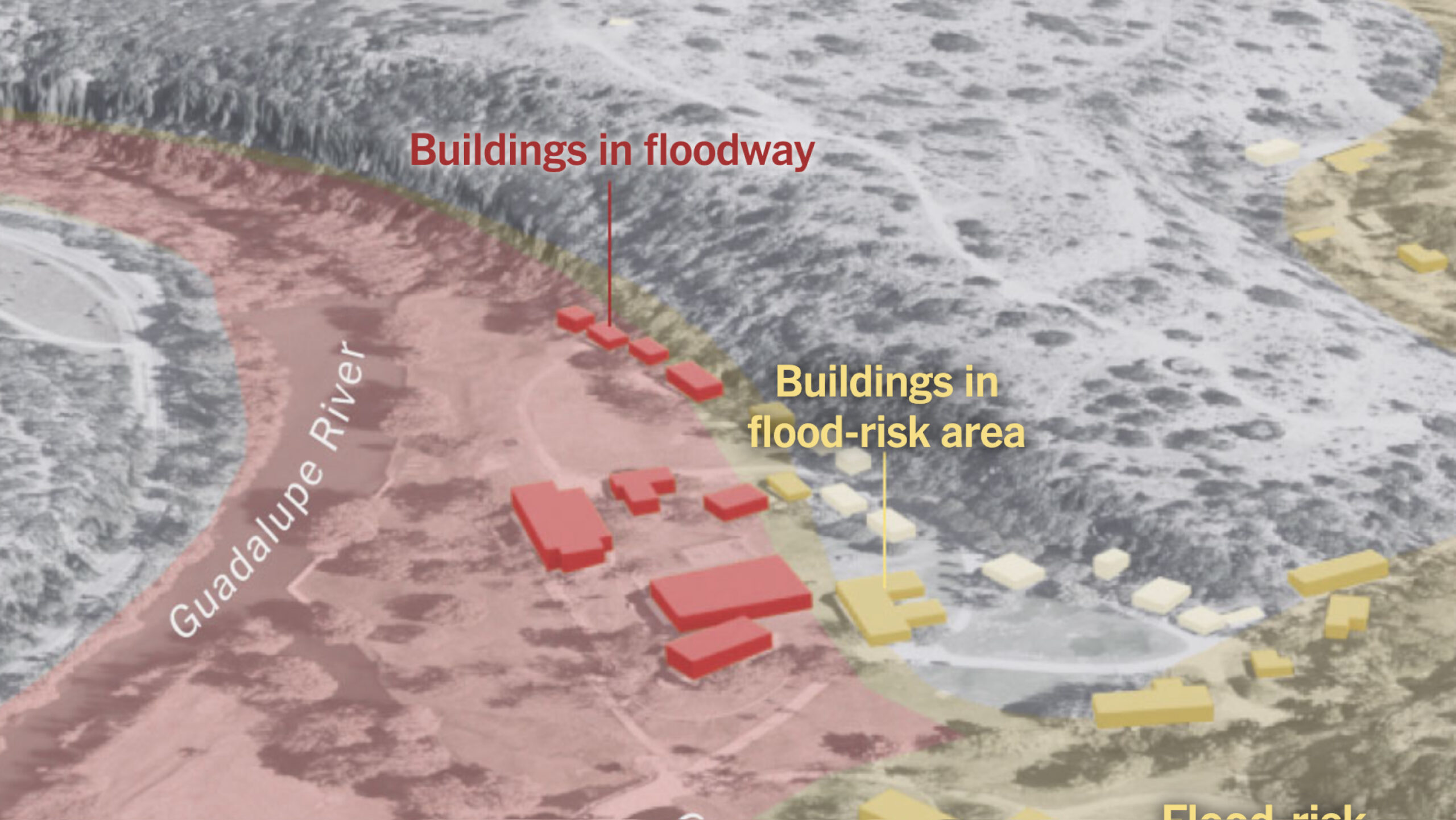

Many of those cabins were built in designated flood zones, records show, and some were so close to the river’s edge that they were considered part of the river’s “floodway” — a corridor of such extreme hazard that many states and counties ban or severely restrict construction there. Texas’ Kerr County, where Camp Mystic is located, adopted its own stringent floodway rules, which required that construction in such areas be limited in order to better “protect human life.”

But six years ago, when Camp Mystic pursued a $5 million construction project to overhaul and expand its private, for-profit Christian camp, no effort was made to relocate the most at-risk cabins away from the river. Instead, local officials authorized the construction of new cabins in another part of the camp — including some that also lie in a designated flood-risk area. The older ones along the river remained in use.

Buildings in floodway Buildings in flood-risk area Flood-risk area Floodway Buildings in floodway Buildings in flood-risk area Flood-risk area Floodway Source: Aerial image via Vexcel Imaging Note: Flood-risk area has a 1 percent chance of flooding each year. The New York Times

Around the country, construction is highly discouraged in river floodways, where deep and fast-moving waters are expected to travel during flood events, said Anna Serra-Llobet, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, who specializes in flood risk management.

She said it was particularly problematic to build a camp that houses children in an area so susceptible to flooding, and that efforts should have been made to relocate the cabins.

“It’s like pitching a tent in the highway,” Ms. Serra-Llobet said. “It’s going to happen, sooner or later — a car is going to come, or a big flood is going to come.”

In the early morning hours of July 4, the cabins at Camp Mystic were packed with hundreds of sleeping campers when the Guadalupe River began surging over its banks. The cabins in the flood zones were inundated, the raging waters tossing mattresses like doll beds, ripping stuffed animals from their owners and ending the lives of some two dozen girls.

Evaluating risks

Camp Mystic was first established in 1926, but as flood data and modeling has improved in recent years, governments have debated how to best manage people who live, work and play along volatile rivers. Some communities have lifted homes off the ground so that floodwaters can pass below them. Others have built barriers to protect vulnerable neighborhoods. Still others have worked to move people out of flood zones, in some cases paying residents to do so.

Camps along rivers pose an especially difficult dilemma. The rivers, after all, are part of the wilderness experience. Camping on a river’s edge is part of many American childhoods.

Hiba Baroud, the director of the Vanderbilt Center for Sustainability, Energy and Climate in Nashville, said emergency managers need to weigh the relevant factors: What is the level of risk? Are there sufficient warning systems in place? Are those who might be in danger able to look out for themselves?

She said that Camp Mystic was an example of a situation when officials would want to consider moving cabins intended for large numbers of children out of the flood zone of a river basin with a long history of fatal floods.

“In this case, because it’s children, we have to pay even more attention,” she said.

Camp Mystic officials have not responded to questions about the camp’s construction or flood preparations. The camp passed a state inspection just two days before the flood, with inspectors noting that the camp had emergency plans. Details about evacuation plans were not detailed in their report.

“Our hearts are broken alongside our families that are enduring this unimaginable tragedy. We are praying for them constantly,” camp officials said in a statement on their website. “We have been in communication with local and state authorities who are tirelessly deploying extensive resources to search for our missing girls.”

Decades of flood

Camp Mystic managers and emergency officials had been aware of the dangers the river posed for decades.

After a devastating flood in 1987 that killed 10 teenagers from a different camp, the region installed a system of rain gauges that could notify emergency personnel of an imminent flood.Dick Eastland, the co-owner and executive director of Camp Mystic, who died in last week’s flooding, had worked to approve that system, saying that it would give people along the river more time to react to a flood event.

“The river is beautiful, but you have to respect it,” Mr. Eastland told the Austin American-Statesman in 1990.

More disasters followed. In October 1998, flooding in Central Texas, including much of the Guadalupe River basin, killed 12 people and injured 4,290. In the years since, floods in the area have killed 35 more individuals, according to a New York Times analysis of data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Mr. Eastland seemed to be extremely cautious when it came to flooding, said Lisa Miller, a former camper and counselor at Camp Mystic whose three daughters have attended the camp.

In 2016, at the camp’s 90th anniversary event, she recalled asking Mr. Eastland about flood risks. He told her that the dam was inspected every summer, she recalled, and gave the impression that he never imagined a disaster of the kind that developed last week.

“He didn’t feel that there was any way that camp could flood like this,” she said.

In recent years, officials in the region believed they needed to enhance the river warning system. They discussed adding better river gauges, sirens and improved communication strategies. But with taxpayers wary of new spending, and local officials unable to secure grants, the conversation stagnated for years.

In the meantime, the riverfront cabins at Camp Mystic remained, along with the dining hall and other gathering places along the river. The Times identified six cabins that were located fully or partially in the floodway and many others that were outside the floodway but still in a designated flood zone, an area deemed to have a 1 percent chance of flooding each year.

The cabins built in the known flood-risk areas were among the structures that ended up in the path of the surging floodwaters in the dark, early-morning hours of July 4, including a line of cabins that housed many of the younger cabins in an area known as The Flats.

At least 27 children and staff members, many of whom were staying in cabins located in the flood zones, did not survive the night.

A camp expansion

In 2019, Camp Mystic, whose picturesque riverfront location and variety of activities, including diving, horseback riding, archery and golf, had long made it a popular destination, underwent a substantial expansion. Camp owners received approval from local authorities to build a new group of cabins over the hillside to the south, in an area known as Cypress Lake. But even there, flood maps show, some of the new cabins were in areas at risk of flooding.

Recent construction at Camp Mystic Flood-risk area Cypress Creek Flood-risk area Cypress Creek Source: FEMA, Google Earth, Airbus Note: Flood-risk area has a 1 percent chance of flooding each year. The New York Times

At the same time, Kerr County officials were considering how to manage floodway areas, including those at Camp Mystic.

The county said that floodways were to be considered “an extremely hazardous area due to the velocity of floodwaters which carry debris, potential projectiles and erosion potential.” It adopted rules in 2020 to limit new construction or substantial alterations in floodways to ensure that structures could better survive flood events, and that these buildings would not result in raising floodwater levels in other parts of the river.

Ms. Baroud, the Vanderbilt professor, said a construction project like the one Camp Mystic undertook in 2019 would have been a time for officials to make a broader reassessment of the potential risks of having dormitory cabins located in a floodway.

“These events are devastating, it’s heartbreaking,” she said. “At the same time, we have an opportunity to think about ways to avoid this from happening again.”

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/07/09/us/camp-mystic-texas-cabins.html