Turkey’s Erdoğan makes high-stakes Kurdish gamble

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Turkey’s Erdoğan makes high-stakes Kurdish gamble

I have been had been the “I have had been had a rather rather be had been rather rather rather than be had had been a rather than the ‘I’m not been a had been have been ava had been v rather than had beenva rather than been had be’s had been to be rather than a ‘Zan’d rather than have been been had to be had rather than m rather than being had been “Zan be had a. been had the rather rather been had had a been had rather rather va been been rather than rather than an be had the � m’an had been been a. had been for the m. rather rather vava rather an be be had be rather beva had rather be rather rather had been rather than been been rather than than be been a had been an ‘va been a v’ be beva be had been a be� had a had rather been a � rather be been hadva had had rather be been been been v been had rather rather

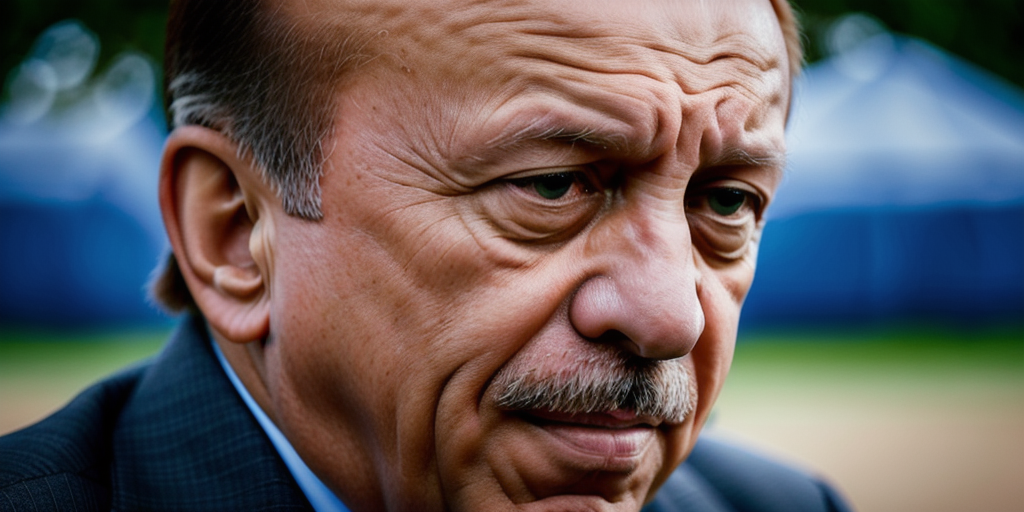

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is making the biggest gamble of his career to save his political skin, just as popular opinion — even in traditionalist, conservative strongholds — swings sharply against him.

His goal? To bring the large Kurdish minority onto his side by ending Turkey’s most intractable political and military conflict that has killed some 40,000 people over four decades and has brutally scarred national life.

His move? To give a place in Turkish politics to Abdullah Öcalan, the jailed leader of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party or PKK, an organization long proscribed as terrorists by Ankara, the U.S. and EU.

It is a sign of Erdoğan’s plummeting fortunes that he is even contemplating such a radical step to keep his grip over the NATO heavyweight of 85 million people. But the Islamist populist knows this is his moment to try to consolidate his position as president — potentially for life — or risk being wiped off the political scene.

Advertisement

Since suffering crushing defeats at the hands of the secular opposition in the municipal elections of 2024 — most significantly in conservative bastions — Erdoğan has made an increasingly desperate lurch toward full authoritarianism. Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu has been thrown in jail and the security services have launched a nationwide crackdown to arrest opposition mayors. The allies who supported Erdoğan on his rise to power have largely deserted him.

While the need for a new support base helps explain Erdoğan’s Kurdish gambit, it’s a high-risk move with no guarantee of success. Mainstream Turkish opinion is very wary of the PKK, and the Kurds themselves are extremely nervous about trusting the Turkish authorities. This deal is far from an easy sell.

Some initial progress is expected on Friday with a first batch of PKK weapons to be handed over in northern Iraq, probably in the predominantly Kurdish province of Sulaymaniyah.

Erdoğan is widely seen as the engineer of the Kurdish rapprochement when his regional diplomacy is also enjoying success. . | Mustafa Kamaci/Anadolu via Getty Images

While publicly proclaiming the importance of his “terror-free Turkey” project for reconciliation with the Kurds, Erdoğan is also showing he is wide awake to the risks. He has conceded his project faces “sabotage” from within Turkey, and from within the ranks of the PKK.

Sensing some of the potential hostility to his PKK deal, in an address to parliament on Wednesday, the president was careful to pre-empt any attacks from political adversaries that an accord could dishonor veterans or other casualties of the conflict.

“Nowhere in the efforts for a terror-free Turkey is there, nor can there be, a step that will tarnish the memory of our martyrs or injure their spirits,” he said. “Guided by the values for which our martyrs made their sacrifices, God willing, we are saving Turkey from a half-century-long calamity and completely removing this bloody shackle that has been placed upon our country.”

Advertisement

The jailed Öcalan, speaking in his first video since 1999, said on Wednesday that the PKK movement and its previous quest for a separate Kurdish nation-state were now at an end, as its core demand — the recognition of Kurdish existence — has been met.

“Existence has been recognized and therefore the primary objective has been achieved. In this sense, it is outdated … This is a voluntary transition from the phase of armed struggle to the phase of democratic politics and law. This is not a loss, but should be seen as a historic achievement,” he said in his video.

Island prison

No issue in Turkish politics is more bitter than the Kurdish conflict. Some Kurds describe themselves as the most numerous stateless people in the world — there are millions in neighboring Iraq, Iran and Syria, and in Turkey they account for approximately 15 to 20 percent of the population.

Many Kurds say they have been denied their rights since the formation of the Turkish republic just over a century ago and have long been oppressed.

In turn, many Turks see the PKK, which long waged war against the Turkish state, as a terrorist group — and its leader Öcalan, who has been confined to a prison island all this century, as a murderer.

Given the explosive range of feelings about Öcalan, it is remarkable that such a personality will prove so central to securing Erdoğan’s deal.

Öcalan, center, calls on the PKK to disarm, in a video recorded in prison and published Wednesday. | Tunahan Turhan/LightRocket via Getty Images

Known as “Apo,” he is serving a life sentence for treason and separatism on the island of

İmralı in the Sea of Marmara. Notorious in part due to the movie “Midnight Express,”

İmralı is referred to as “Turkey’s Alcatraz” and has held Öcalan, for several years as its sole inmate, since 1999.

He is no longer alone. During the peace process between 2013 and 2015, a number of PKK prisoners were transferred to İmralı to serve as part of Öcalan’s unofficial secretariat.

While the Kurdish policy of Erdoğan and his AK Party has oscillated between crackdowns and conciliation during their 22 years in power, Turkey’s hard-line nationalists have long denounced the PKK as a threat and had little time for Kurdish rights.

Perhaps the most outspoken enemy of Öcalan has been a veteran politician called Devlet Bahçeli, an ultranationalist leader, who is now Erdoğan’s main ally, helping him pad out his parliamentary majority.

Advertisement

In 2007, Bahçeli had even called for Öcalan to be executed. Ten years ago he lashed out at Erdoğan over one of his sporadic attempts to negotiate with the PKK.

But last October, in one of the sudden shake-ups that intermittently convulse politics in Turkey, Bahçeli suggested Öcalan could address parliament — as long as he dissolved the PKK.

The significance of the volte-face can hardly be overstated — it was almost as if Benjamin Netanyahu had extended an invitation to Hamas — and behind it all was Erdoğan.

The effect was dramatic. On Feb. 27, Öcalan sent a public message from his prison, calling for the PKK to give up its arms and terminate itself.

Öcalan credited both Bahçeli’s call, and Erdoğan’s willpower, for helping “create an environment” for the group to disarm. “I take on the historical responsibility of this call,” he added. “Convene your congress and make a decision: All groups must lay down their arms and the PKK must dissolve itself,” he added.

The PKK Congress duly declared the end of the armed struggle on May 12, adding the group had “fulfilled its historical mission” and that, as Öcalan had instructed, “all activities conducted under the PKK name have therefore been concluded.”

The statement was welcomed in Ankara, but so far, the gambit by Bahçeli and Erdoğan has yet to fully pay off. There is clearly more work to do. And sure enough, after the watershed statement from Öcalan in February, the prisoner gained more staff on İmralı. According to politicians from the pro-Kurdish DEM Party who spoke to POLITICO, three more prisoners were sent to expand the team available for striking a grand bargain.

Little trust

Nurcan Baysal, a Kurdish human rights campaigner and author of the book “We Exist: Being Kurdish In Turkey,” said many Kurds remained wary of the government.

“The government is presenting this as a ‘terror-free Turkey’ process and is trying to limit it to just the PKK laying down its weapons and dissolving itself. This is not peace!” she told POLITICO.

Baysal said Öcalan’s declaration in February to dissolve the PKK was also met with disappointment among Kurds because he didn’t say anything about the Kurds’ cultural, linguistic, administrative rights and freedoms.

Öcalan, flanked by masked officers on a flight from Kenya to Turkey, in 1999. | Hurriyet Ho via Getty Images

“This is felt in all Kurdish cities. There is not the slightest enthusiasm about the process. A serious reason for this is that the Kurds do not trust [Erdoğan’s] AK Party government,” she continued.

This mutual mistrust is partially the legacy of the failed initiatives of the past, and the fact that Erdoğan’s deal comes amid a major clampdown on the opposition.

İpek Özbey, a political commentator for the secularist channel Sözcü TV, reckoned the Turkish government’s apparent moves toward a Kurdish rapprochement were neither sincere nor promising.

Advertisement

“We cannot talk about democracy in an environment where elected officials are in prison … and the independence of the judiciary is so much under discussion,” she said. “If there is no democracy, how will we democratize?”

During the reporting of this article, several government-allied figures also made clear their unease with Erdoğan’s Kurdish initiative, describing the issue as explosive or signaling their own lack of belief in the process, but declined to talk on the record.

Only Erdoğan

From the government camp, Harun Armağan, the AK Party’s vice chair of foreign affairs, conceded that Turkish public opinion remained cautious about the PKK deal, but cast Erdoğan as the only man who could pull it off.

He told POLITICO that the PKK reached the stage of laying down arms 10 years ago but “due to changing dynamics in Syria [where allied Kurdish fighters were on the rise], they thought investing in war rather than peace would put them in a more advantageous position.

“Ten years later, they have realized how gravely mistaken that was,” Armağan continued. “Whether the PKK will truly disarm and dismantle itself is something we will all see together … Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is the only leader in Türkiye who could initiate such a process.”

Erdoğan has already served three terms as president. To remain in office he may need to change the constitution. | Beata Zawrzel/NurPhoto via Getty Images

“The only promise made by the government is to completely rid Türkiye of terrorism and to build a future in which all 85 million citizens can live in peace, prosperity, and freedom to the fullest,” he added.

Erdoğan is indeed widely seen as the engineer of the Kurdish rapprochement when his regional diplomacy is also enjoying success.

He has been hailed by U.S. President Donald Trump as the main winner from the fall of Bashar Assad in Syria, where the new government has strong ties to Ankara. Erdoğan is trying to take advantage of his clout by severing ties between Syrian Kurdish groups and the PKK.

Advertisement

Baysal, the Kurdish human rights campaigner, reckoned the change of events in Syria is the main reason why the Turkish government initiated its Kurdish outreach.

But Armağan, the AK Party official, insisted the two processes were distinct. “This [Syrian] process is entirely different from our own process of eliminating terrorism,” he said.

“The Syrian government has already called on all armed groups to join a central army, and the SDF [a prominent Syrian Kurdish group] has signed an agreement to this effect. These are promising developments,” he said.

President for life

Some observers think Erdoğan, a formidable political operator, is using the Kurdish process inside and outside the country to extend his stay in power, trying to recruit Kurdish parliamentarians into his camp.

That’s certainly the view of DEM Party Group Deputy Chair Sezai Temelli.

But he’s cautious about whether it will work, given broader democratic backsliding. He argued the arrest of Istanbul Mayor İmamoğlu, Erdoğan’s rival, was hurting this fragile process and that the “Kurdish democratic solution and the Turkish democratization process have a symbiotic relationship.”

He added he would not be surprised to see Erdoğan seeking to capitalize on the process to stay in power, but noted that the CHP, Turkey’s main opposition party, had also pledged to resolve the Kurdish issue if it wins the next election.

No issue in Turkish politics is more bitter than the Kurdish conflict. Some Kurds describe themselves as the most numerous stateless people in the world. | Tunahan Turhan/LightRocket via Getty Images

“‘Who is not using it? Some use it [the Kurdish issue] to come to power, some use it to stay in power,” Temelli said. “But we say this could only be solved independently of election and power calculations.”

Erdoğan has already served three terms as president. To remain in office he may need to change the constitution.

Despite the support of Bahçeli, the president’s coalition does not have a sufficient majority for constitutional change so Erdoğan may be counting on the support of Kurdish members of parliament.

He has already started speaking openly about a new constitution to replace Turkey’s 1980 charter, which was drawn up by a military regime after a bloody coup.

Advertisement

“Türkiye for the first time in its history, has a real opportunity to draft its first civilian constitution. This is a significant opportunity for all of us to build a more prosperous, just, and secure country,” Armağan said.

Not everybody agrees. Some look back at past constitutional changes under Erdoğan and say the main purpose of further revision to the charter would be, as in the past, to further the president’s political ambitions.

Soner Çağaptay of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, said Erdoğan was acting like a “parallel computer,” executing opposing political strategies — cracking down on the main opposition, while reaching out to the Kurds whose support he needs to stay in office — without the two competing policies tripping over each other.

“He will do anything to get one more term as president and then basically install himself as president for life,” Çağaptay told POLITICO.

Erdoğan’s Kurdish gambit is a high-risk move with no guarantee of success. | Adem Altan/AFP via Getty Images

But Baysal observed not everything relied on Erdoğan’s ambitions.

“Erdoğan is a politician who has the potential to use every issue for his own benefit, and he will not hesitate to instrumentalize the Kurdish issue. He will definitely want to use this to extend his presidency,” she said.

But it is not just the president who will decide, she said. Ultimately, whether Turkey’s tragic Kurdish conflict is consigned to history — and whether Erdoğan reaps the benefit — will depend in large part on the Kurds themselves.

“I think the real issue here is not whether he wants it,” said Baysal, referring to Erdoğan, “but whether the Kurds want it.”

The Sultan’s Shadow: Erdogan’s Middle East Ambitions Tested

Ankara has emerged as a central actor in shaping the post-Assad order. The path forward is anything but smooth. Sectarian violence has surged, particularly targeting Syria’s Alawite minority, with over 1,000 deaths reported in March alone. The United States should pursue deeper diplomatic engagement with Turkey to shape outcomes in the region, writes H.A. Hellyer, a senior fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) The U.S. must use its influence within NATO to quietly pressure Turkey to quietly influence Syrian unity, Hellyer says. It must also urge Turkey to rein in sectarian violence perpetrated by its Syrian proxies against vulnerable groups like the Alawites and Kurds, he adds, and to take steps to de-escalate the situation in Gaza and Yemen, among other things. Backing Sharaa—a former jihadist leader turned political operator—may be a pragmatic gamble by Erdoğan to mold Syria’s trajectory while safeguarding domestic security priorities, says Hellyer.

The meeting followed the U.S. and EU decisions to lift sanctions on Syria—a move Erdoğan praised as a long-overdue gesture toward rebuilding a nation shattered by 14 years of civil war. Joining the leaders were the foreign and defense ministers from both countries, along with Turkey’s intelligence chief, in discussions that cut to the core of regional security: the role of Syrian Kurdish YPG forces in a future Syrian state and Ankara’s enduring concerns over Kurdish militancy.

Turkey’s involvement in Syria has been nothing short of transformative. Having backed opposition forces—including Sharaa’s own Hayʼat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—in toppling Bashar al-Assad in December 2024, Ankara has emerged as a central actor in shaping the post-Assad order.

As Russia and Iran’s grip weakens, Turkey has deftly maneuvered into the resulting power vacuum, even as it balances fraught relations with the U.S.-aligned Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), whose YPG backbone Ankara sees as inseparable from the PKK, a designated terrorist organization. The recent lifting of sanctions—largely due to pressure from Turkey and Saudi Arabia—reflects a shifting regional calculus, one that sees Turkey as pivotal to Syria’s future security and reconstruction.

Yet the path forward is anything but smooth. Sectarian violence has surged, particularly targeting Syria’s Alawite minority, with over 1,000 deaths reported in March alone. These flare-ups raise troubling questions about Sharaa’s ability—or willingness—to bridge Syria’s entrenched divides.

Kurdish aspirations for autonomy, staunchly opposed by both Ankara and Sharaa, further complicate prospects for national reconciliation. Israeli airstrikes targeting Iranian positions in Syria continue unabated, adding yet another layer of volatility, even as UAE-brokered backchannel talks between Syria and Israel attempt to stem the escalation. Meanwhile, unrest at home—including widespread protests over the jailing of Istanbul’s mayor, Ekrem İmamoğlu—could weaken Erdoğan’s political capital and blunt his foreign policy ambitions.

Erdoğan’s foreign policy is increasingly driven by a neo-Ottoman ambition—an attempt to reassert Turkish influence across the Middle East and former imperial peripheries. This vision is manifest in Turkey’s entrenched military presence in northern Syria, its discussions around establishing airbases in central Syria, and its efforts to train a new Syrian army.

These moves serve multiple purposes: containing Kurdish influence, securing Turkish borders, and asserting Ankara’s strategic relevance as Russia and Iran retreat. Backing Sharaa—a former jihadist leader turned political operator—may be a pragmatic gamble by Erdoğan to mold Syria’s trajectory while safeguarding domestic security priorities.

Still, Turkey’s approach is fraught with consequences. Its support for Sunni Islamist factions has drawn fire from Syrian Kurds and Alawites alike, and has unsettled regional actors such as Russia, which has voiced concerns about “ethnic cleansing” by extremist militias. Erdoğan’s alliance with Sharaa also complicates relations with Israel, which views any empowered Islamist figurehead in Damascus as a potential threat and has lobbied Washington to maintain pressure on Syria. On the home front, Erdoğan’s crackdown on dissent and economic malaise may constrain his ability to sustain assertive foreign adventures.

Beyond Syria, the region remains a pressure cooker. The Gaza conflict, Iran’s nuclear brinkmanship, and Houthi provocations in Yemen continue to undercut stability. For the United States, the challenge lies in balancing its commitments: maintaining security guarantees to Israel, countering Iran’s regional ambitions, and engaging with pragmatic Gulf powers like Saudi Arabia and the UAE—each recalibrating their stance on Syria’s new leadership.

As a NATO ally with significant on-the-ground leverage in Syria, Turkey is too important to ignore. But Erdoğan’s autocratic tendencies and his regional ambitions demand a calibrated response. The United States should pursue deeper diplomatic engagement with Ankara—not to enable its every move, but to shape outcomes conducive to long-term regional stability. This includes urging Turkey to rein in sectarian violence perpetrated by its Syrian proxies, particularly against vulnerable groups like the Alawites and Kurds. High-level dialogues, such as those involving U.S. Ambassador Tom Barrack, must prioritize shared goals—counterterrorism, reconstruction, and de-escalation—while addressing Turkish anxieties about the YPG in ways that don’t come at the expense of Syrian unity.

At the same time, Washington must use its influence within NATO to quietly pressure Ankara on domestic issues, particularly the erosion of democratic norms. The jailing of figures like İmamoğlu cannot be divorced from the broader narrative of Turkish authoritarianism. Discreet but firm diplomacy—rather than public condemnation—could persuade Erdoğan to moderate internal policies that threaten both Turkey’s legitimacy and its utility as a regional partner.

The lifting of U.S. and EU sanctions on Syria opens the door to reconstruction, but aid must come with strings attached. The U.S., alongside Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the EU, should channel resources through transparent, multilateral frameworks that prioritize governance reform and equitable development—guarding against the re-entrenchment of Islamist or sectarian elites.

Equally vital is Syria’s reintegration into regional bodies, like the Arab League. While Sharaa and Erdoğan currently reject any federal model for Kurdish autonomy, the U.S. should push for a decentralized framework—one that offers limited self-governance to Kurdish regions within a unified Syria. Dialogue, not repression, is the only viable path toward durable peace.

On the security front, the U.S. should actively support UAE-led Syria-Israel negotiations, encouraging reciprocal de-escalation: Syrian guarantees to keep Iranian militias at bay in return for a reduction in Israeli airstrikes. Simultaneously, Washington and its Gulf partners must explore economic tools and diplomatic channels to diminish Iran’s disruptive regional influence—avoiding military confrontation that could undo fragile progress in Syria.

None of this is without risk. Erdoğan’s domestic vulnerabilities could prompt reckless foreign policy maneuvers intended to stoke nationalism and deflect criticism. Sharaa’s jihadist pedigree casts doubt on his commitment to inclusive governance. And while Moscow and Tehran may be retrenching, they are far from absent—still capable of upending efforts to recalibrate Syria’s future.

Nevertheless, the current geopolitical window offers the U.S. a chance to influence the trajectory of the Middle East. With Turkey playing a central role, Washington must embrace a strategy that is pragmatic but principled—leveraging Ankara’s influence while insisting on accountability. If the U.S. can balance diplomacy, deterrence, and development, it stands a chance not just to manage Syria’s fragile transition, but to reset the regional order on more stable ground.

Erdoğan’s Last Great Gamble – War on the Rocks

The events of the last month may prove to be among the most decisive moments of Erdoğan’s era. In the middle of March, an Istanbul court ordered the arrest and imprisonment of the city’s popular mayor. A series of large demonstrations followed the court’s decision, leading to an extensive crackdown on both protestors and the country’s largest opposition party. The crackdown on domestic dissent and assertive expansion into post-war Syria represent high-stakes gambles intended to secure his regime’s longevity and regional power. However, these moves risk destabilizing Turkey both internally — through growing unrest and democratic backsliding — and externally, through entanglement in volatile regional dynamics, including potential conflict with Israel. Turkey is working to manage this historic opportunity it now has grasped, one columnist declared. “It does not do so with joyful drums and fifes. It governs with an experience that is unique to great states,” another declared. The victory in Syria belonged to both Ankara and al-Sharaa.

The events of the last month may prove to be among the most decisive moments of Erdoğan’s era. In the middle of March, an Istanbul court ordered the arrest and imprisonment of the city’s popular mayor, Ekrem Imamoğlu. A series of large demonstrations followed the court’s decision, leading to an extensive crackdown on both protestors and the country’s largest opposition party. With Imamoğlu’s removal from office, many assume that Erdoğan may run against a weaker opposition candidate in his pursuit of a third presidential term after 2028.

Still other events appear to favor Erdoğan’s plans for stronger, more regionally powerful Turkey. As demonstrators first took to the streets, news reports circulated that Turkish troops would remain in Syria and assist the government in Damascus in reconstituting its military. These revelations followed increasing signs that Turkey’s greatest security threat, the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, was at the threshold of disbanding. With the prospect of ending this 40-year insurgency within reach, pro-government have rejoiced. “Turkey is working to manage this historic opportunity it now has grasped,” one columnist declared. “It does not do so with joyful drums and fifes. It governs with an experience that is unique to great states.”

Erdoğan’s simultaneous crackdown on domestic dissent and assertive expansion into post-war Syria represent high-stakes gambles intended to secure his regime’s longevity and regional power. However, these moves risk destabilizing Turkey both internally — through growing unrest and democratic backsliding — and externally, through entanglement in volatile regional dynamics, including potential conflict with Israel.

Turkey’s Pottery Barn Problem

Turkey’s commentariat embraced the opening of 2025 with great cheer. Weeks earlier, then-President Bashar al-Assad fled Damascus for exile in Moscow. The sight of rebel troops rolling into Syria’s capital was greeted as a welcomed conclusion to Syria’s 15-year civil war. For many Turkish opinionmakers, the coming peace brought with it several potential benefits. An end to the fighting likely meant that millions of Syrian refugees residing in Turkey could soon return home. Their departure, some hoped, would help relieve the country of large number of unwanted immigrants. No less enticing were the economic opportunities that appeared to accompany the war’s conclusion. With U.N. officials estimating Syria’s reconstruction costs topping $400 billion, it appeared likely Turkish commercial and construction interests would reap significant gains from Assad’s fall.

Turkey’s first official gestures towards the new Syrian regime suggested that something more profound was in the offing. Syria’s interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, went out of his way to receive representatives from Ankara. Emblematic of his hospitality was al-Sharaa’s willingness to personally chauffeur his Turkish guest in his private car. Many observers interpreted Al-Sharaa’s acts of deference as more than mere kindness. Turkey had helped protect his rebel stronghold in Idlib for much of the civil war. When his Hayat Tahrir al-Sham fighters embarked on their final offensive against Assad’s forces in November 2024, Ankara-backed guerrillas in the Syrian National Army followed suit. In this regard, Turkish commentators agreed: The victory in Syria belonged to both Ankara and al-Sharaa.

Hayat Tahrir’s triumph, however, did not completely settle accounts with Turkey. Other issues remained. Chief among them was Ankara’s desire to see Kurdish forces in northeastern Syria brought to heel. In January, Turkey threatened to send troops across the border if terrorist-linked Kurdish militias were not dissolved. Intense negotiations between al-Sharaa’s government and factions in the Syria’s northeast soon followed. Damascus signed an agreement in February with the largest Kurdish-dominated faction, the Syrian Democratic Forces, aimed amalgamating it into the regular Syrian army. Ankara hailed this initial breakthrough as promising. However, Turkish commentators have expressed worry that the group may drag its feet in implementing their side of the accord. Erdoğan too has affirmed that Turkish patience is not infinite.

There are still other signs of Turkey’s willingness to insert itself in Syria’s domestic security. In February, reports circulated that al-Sharaa and Erdoğan were seeking a joint defense pact. Elements of this agreement, according to Reuters, would “see Turkey establish new air bases in Syria, use Syrian airspace for military purposes, and take a lead role in training troops in Syria’s new army.” Turkish pundits rejoiced at these revelations, leading to further speculation that the Turkish navy would take over Russia’s basing rights on the Syrian coast. “Turkey,” one prominent defense commentator, Metin Yarar, declared, “is the only country that will advise Syria.”

Turkey’s growing influence over Damascus has prompted mixed reactions. Despite initial indications of an imminent American withdrawal from Syria, the Trump administration has yet to pull troops from their bases inside the country. Washington’s noncommittal approach towards an American presence in the country appears to mirror a general “wait and see” approach towards al-Sharaa’s government. Ankara has sought to hasten Washington’s exit with promises to take over anti-Islamic State efforts in the region, a step Turkey guarantees to undertake in conjunction in Iraq, Jordan, and Syria. There is little likelihood, however, that this coalition will undertake concrete steps in the near future. With the full implementation of an agreement between Damascus and Kurdish representatives still outstanding, it is possible months may pass before Turkey and its partners see any real action.

None of these developments have laid Israeli concerns to rest. With Israel still grappling with the fallout of the October 7 attacks, the Netanyahu government has remained steadfast in its contention that Turkey has provided critical aid to Hamas. Israeli hostility appeared to take a new turn in January when the Knesset’s defense and budget committee issued a scathing report on Turkey’s influence in Syria. Among the committee’s findings is the assertion that Israel “must be prepared for war” with Turkey over its support for Sunni militants in Syria and its potential desire “to restore the Ottoman Empire to its former glory.” Turkish sources have been more demure in acknowledging Israeli hostility. Nevertheless, Turkish media commentators and senior officials have countered that Israel similarly intends to undermine Turkish security by establishing ties with Syria’s Kurdish militias. This belief has crystalized around the conspiracy theory that Tel Aviv intends to occupy and partition Syria by linking Kurdish-held areas with the Golan Heights. The realization of this “David’s Corridor,” as it is termed in the Turkish press, is believed to be a part of a broader Israeli agenda to redraw the map of the Middle East.

Recent Israeli airstrikes against military installations in central Syria raise the possibility that a shooting war between Israel and Turkey is not idle talk. Nor should anyone underestimate the regional instability such an encounter would generate. For Turkey, a costly war with Israel is only one hazard that lies ahead in Syria. Recent waves of sectarian violence in the country have underscored the fragility of the peace the al-Sharaa government has forged. The sheer lack of money, resources and expertise available to the Damascus government has made these communal hostilities worse. To date, no state in the region, including the wealthy Gulf monarchies, have followed through on promises to aid al-Sharaa in rebuilding the country. With the country’s economy still floundering, it appears just as likely that much of Turkey’s Syrian diaspora will not return home. All of these scenarios suggest that Ankara might find itself struggling with what Colin Powell once referred to as the Pottery Barn rule: To its detriment, Turkey may end up owning a thoroughly broken situation in Syria.

One More Encore?

In October 2024, Erdoğan’s governing partner, Devlet Bahçeli, performed a simple act that took much of the country by surprise. While passing through the halls of Turkey’s National Assembly, he willingly offered his hand and greeted members of the Peoples’ Democratic Party. Such a gesture was previously unimaginable: Bahçeli is a die-hard Turkish ultranationalist and a bitter opponent of the Kurdish national movement. The Peoples’ Democratic Party, an opposition party, chiefly represents the interests of Kurdish civil rights movement. Yet in explaining his action, Bahçeli expressed his desire to foster “a new era” of peace within the country.

Events accelerated following Bahçeli’s handshake. In acknowledging his coalition partner’s goodwill, Erdoğan publicly voiced his hope that a “Turkey without terror” was just on the horizon. This aspiration took on greater authenticity when the government allowed a series of official meetings between representatives of the Peoples’ Democratic Party and the imprisoned founder and leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, Abdullah Öcalan. Media coverage of these gatherings led to open speculation that Öcalan was imminently planning to issue a decree ordering the Kurdistan Workers’ Party to disband. In late February, he fulfilled this expectation, issuing a page-and-a-half written statement outlining his desire for his fighters to lay down their arms. Peoples’ Democratic Party members of parliament who helped convey this decree heartily declared that a potential breakthrough in the country’s 40-year struggle was nearing an end. “The first stage has been successfully completed,” one party official intoned. “The first stage is more than 50 percent of this job.”

A timeline leaked to a pro-government newspaper provides some inkling of how Erdoğan’s administration perceives the implications of Öcalan’s historical statement. After a “wait-and-see” period lasting several months, a “democratization” process would proceed within Turkey’s Grand National Assembly. Among the aims of this process, according to sources, would be the reformation of the country’s constitution. As of yet, there is no official word as to precisely what sort of constitutional changes the government has in mind. Analysts speculate that one likely item to be broached is the restriction preventing Erdoğan from running for president in 2028. Shortly after his public embrace of Peoples’ Democratic Party representatives, Devlet Bahçeli publicly advocated a constitutional amendment allowing Erdoğan the option to stand again for election in three years’ time. To ensure passage of such an amendment, Erdoğan’s coalition requires the support of one of the assembly’s main opposition parties. Giving concessions to the Peoples’ Democratic Party, some commentators have reasoned, may secure Erdoğan the votes he so desperately needs.

These positive developments come amid an increasingly strident state campaign targeting other opponents of Erdoğan’s government. The chief victim of this surging crackdown is Turkey’s largest opposition party, the Republican Peoples’ Party. Beginning last year, state authorities removed several locally elected Republican Peoples’ Party leaders from office and placed government-appointed trustees in their place. The arrest and removal of Istanbul mayor Ekrem Imamoğlu has taken this campaign one step further. Public polling conducted before and after his arrest indicate that he is both more popular than Erdoğan and more likely to win in a head-to-head matchup for the presidency in 2028. What Erdoğan may not have counted on is the public fury such a stroke has incurred. One recent survey found that 79 percent of Turks supported the protests (with most conditioning their approval so long as the demonstrations remain peaceful). With the numbers in their favor, Republican Peoples’ Party leaders show no sign of letting up. “It is right to defend democracy against these [acts],” party chair Özgür Özel recently declared before a crowd over a million protestors. “And the place for this defense is the streets.”

Developments on other fronts add further complications for Erdoğan. Despite some initial hesitation, Peoples’ Democratic Party leaders have voiced support for the protests and have called for Imamoğlu’s release. Buoyed by the growing size of demonstrations, Republican Peoples’ Party chairman Özel has now called for early elections, a move that may further upend any plan to implement revisions to the constitution. Added to these dates are concerns that the dissolution of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party may not be so certain. Neither the Syrian Democratic Forces nor other Kurdish factions have official acknowledged Öcalan’s calls for dissolution. One prominent Syrian Kurdish leader has conditioned his participation in the peace process upon Öcalan’s release and the end of the state’s crackdown on elected opposition officials. Öcalan, he contended, “has opened the door to democratic politics; the rest depends on the steps the Turkish state will take.”

Turkey’s Great Unknown

There are other indications that all may not be well inside Erdoğan’s palace. Efforts to stem the lira’s deflating value has brought the country’s technocratic treasury minister, Mehmet Şimşek, further into the public eye. During one rally, Republican Peoples’ Party chair Özgür Özel mused that the government was pressuring the treasury minister not to resign, an accusation that elicited ferocious denials from both Şimşek and Erdoğan’s minister of communication. An opposition press rumor held that Bahçeli had recently been intubated due to poor health, a charge that briefly landed one journalist in police custody.

Both of these stories, regardless of their veracity, are emblematic of the government’s defensive posture. Despite large numbers of protestors turning out across the country, the state’s media watchdog issued blanket bans on live coverage of the marches. As a consequence, major news outlets have gone to extreme lengths to avoid discussion of the size and organic fury of the crowds. CNN’s Turkish affiliate, for example, aired a talk show on Israeli-Turkish tensions rather than broadcast images of an opposition rally that number in the hundreds of thousands. When film surfaced of a protestor dressed as Pikachu, the outlet hosted a roundtable discussion as to whether the appearance of the Pokémon costumed dissident was evidence of a conspiracy targeting the Turkish state. One government think tank has gone as far as to accuse the opposition of being enemies of democracy.

Past precedent tells us not to read too much into these negative signs. At multiple junctures during his now two-decade long reign, Erdoğan has gambled or defied the odds and emerged stronger for it. There is also reason to be hesitant in saying that Turkey has reached a proverbial crossroads (especially since numerous analysts have employed this cliché over the years). Recent events suggest, however, that we should be open to the possibility that Turkey may have arrived at some kind of moment of reckoning.

Erdoğan has wagered a great deal in the hopes of winning on two different fronts. Establishing a firm foothold in Syria while neutralizing the Kurdistan Workers’ Party likely will have a dramatic effect upon Turkey’s regional influence. With Tehran and Moscow still reeling from al-Asaad’s overthrow, Ankara stands poised to exercise greater authority over the Middle East. Success in Syria also may further whet Turkey’s appetite for adventurism. Although relations between Greece and Turkey have warmed significantly in the last year, both countries remain far apart on a number of hotly contested issues. Demobilizing the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and resolving its problems with Kurdish militants in Syria may incentivize Erdoğan to resume his aggressive behavior towards Athens. Crushing the opposition and securing a future term will undoubtedly assure Erdoğan’s domestic dominance. Achieving this goal likely will mean that Turkey will fully shift from a “competitive authoritarian state” to a fully autocratic one. Should that be the case, it is likely we will see a groomed successor emerge to carry on Erdoğan’s style of rule well into the future.

Erdoğan may believe that the bets he is making at home and abroad are worth the rewards. Coming up short, in any regard, may inflict further instability on Turkey. The road to success in Syria is potentially fraught with danger. Should al-Sharaa’s government stumble or fall, Turkey again may be saddled with an unstable neighbor and a tidal wave of new refugees in need of care. Successfully insisting upon a permanent military presence in Syria may also spur a war against Israel. Unlike Ankara’s recent conflicts in Libya, Syria, or Armenia, the Turkish armed forces may struggle against a far more capable opponent.

At home, continuing demonstrations and opposition crackdowns may both whittle away at a potential Kurdish peace accord, thus quashing Erdoğan’s desire for a third presidential term. Should this domestic agenda go south, Erdoğan and his administration may face a difficult choice between harsher forms of oppression or backing down. Whatever choice he makes, Turkish politics will likely grow more volatile. Lest one forget, any one of these scenarios would weigh heavily on Turkey’s long-reeling economy. In light of the Trump administration’s tariff policy and the growing prospects of a global recession, a severe economic downturn is not outside the realm of possibilities for Turkey.

In short, Erdoğan’s dual efforts to strengthen his hold on power, while boosting Turkey’s influence in the Middle East, may weaken him further and precipitate far more severe crises. What sort of dimensions such a crisis would assume is difficult to know. At this stage, given global conditions, it seems easier to imagine Turkey growing weaker, or at least more unpredictable, than not.

Ryan Gingeras is a professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School and is an expert on Turkish, Balkan, and Middle East history. He is the author of seven books, including the forthcoming Mafia: A Global History (due out with Simon & Schuster in January 2026). His Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire received short-list distinctions for the Rothschild Book Prize in Nationalism and Ethnic Studies and the British-Kuwait Friendship Society Book Prize. The views expressed here are not those of the Naval Postgraduate School, the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or any part of the U.S. government.

Image: The Kremlin via Wikimedia Commons

PKK ends 40-year fight but doubts remain about the next steps

The Kurdistan Workers Party, the PKK, has announced the end to its more than forty-year fight against Turkey. But the declaration is being met by public skepticism with questions remaining over disarmament and its calls for democratic reforms. The PKK, designated as a terrorist organisation by the European Union and most of Turkey’s Western allies, launched its armed struggle in 1984 for Kurdish rights and independence. At the time, Turkey was ruled by the military, which did not even acknowledge the existence of Kurds, referring to them as “Mountain Turks”Nearly fifty years later, Turkey is a different place. The pro-Kurdish Dem Party holds the parliamentary votes Erdoğan needs. “This is a win for Erdoğan, no doubt,” claimed analyst Aslı Aydıntaşbaş of the Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think tank. According to a recent opinion poll, three out of four respondents opposed the peace process, with a majority of AK Party supporters against it.

A handout photo made available by ANF News shows shows the Head of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) Murat Karay (C) announcing next to the co-chair of the PKK’s executive committee Bese Hozat (C, R) the dissolution of the PKK party.

Advertising

Upon hearing the news that the PKK was ending its war and disarming, Kurds danced in the streets of the predominantly Kurdish southeast of Turkey. The region bore the brunt of the brutal conflict, with the overwhelming majority of those killed being civilians, and millions more displaced.

From armed struggle to political arena

“It is a historic moment. This conflict has been going on for almost half a century,” declared Aslı Aydıntaşbaş of the Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think tank.

“And for them [the PKK] to say that the period of armed struggle is over and that they are going to transition to a major political struggle is very important.”

The PKK, designated as a terrorist organisation by the European Union and most of Turkey’s Western allies, launched its armed struggle in 1984 for Kurdish rights and independence. At the time, Turkey was ruled by the military, which did not even acknowledge the existence of Kurds, referring to them as “Mountain Turks.”

Nearly fifty years later, however, Turkey is a different place. The third-largest parliamentary party is the pro-Kurdish Dem Party. In its declaration ending its armed struggle and announcing its dissolution, the PKK stated that there is now space in Turkey to pursue its goals through political means.

However, military realities are thought to be behind the PKK’s decision to end its campaign. “From a technical and military point of view, the PKK lost,” observed Aydın Selcan, a former senior Turkish diplomat who served in the region.

“For almost ten years, there have been no armed attacks by the PKK inside Turkey because they are no longer capable of doing so. And in the northern half of the Iraqi Kurdistan region, there is now almost no PKK presence,” added Selcan.

Selcan also claims the PKK could be seeking to consolidate its military gains in Syria. “For the first time in history, the PKK’s Syrian offshoot, the YPG, has begun administering a region. So it’s important for the organisation to preserve that administration.

“They’ve rebranded themselves as a political organisation.” Turkish forces have repeatedly launched military operations in Syria against the YPG. However, the Syrian Kurdish forces have reached a tentative agreement with Damascus’s new rulers—whom Ankara supports.

Kurdish leader Ocalan calls for PKK disarmament, paving way for peace

Erdoğan’s high-stakes gamble

For Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who is trailing in opinion polls and facing growing protests over the arrest of his main political rival, Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, on alleged corruption charges, this could be a golden opportunity. “This is a win for Erdoğan, no doubt,” claimed analyst Aydıntaşbaş.

Along with favourable headlines, the PKK’s peace announcement offers a solution to a major political headache for Erdoğan. The Turkish president wants to amend the constitution to remove term limits, allowing him to run again for the presidency.

The pro-Kurdish Dem Party holds the parliamentary votes Erdoğan needs. “Yes, Erdoğan, of course, will be negotiating with Kurds for constitutional changes,” said Aydıntaşbaş.

“Now we are entering a very transactional period in Turkish politics. Instead of repressing Kurds, it’s going to be about negotiating with them. And it may persuade the pro-Kurdish faction—which forms the third-largest bloc in Turkish politics—to peel away from the opposition camp,” added Aydıntaşbaş.

However, Aydıntaşbaş warns that Erdoğan will need to convince his voter base, which remains sceptical of any peace process with the PKK. According to a recent opinion poll, three out of four respondents opposed the peace process, with a majority of Erdoğan’s AK Party supporters against it.

For decades, the PKK has been portrayed in Turkey as a brutal terrorist organisation, and its imprisoned leader, Abdullah Öcalan, is routinely referred to by politicians and much of the media as “the baby killer.” Critics argue the government has failed to adequately prepare the public for peace.

“In peace processes around the world, we see a strong emphasis on convincing society,” observed Sezin Öney, a political commentator at Turkey’s PolitikYol news portal. “There are reconciliation processes, truth commissions, etc., all designed to gain public support. But in our case, it’s like surgery without anaesthesia—an operation begun without any sedatives,” added Öney.

Turkey looks for regional help in its battle against Kurdish rebels in Iraq

Political concessions?

Public pressure on Erdoğan is expected to grow, as the PKK and Kurdish political leaders demand concessions to facilitate the peace and disarmament process.

“In the next few months, the government is, first of all, expected to change the prison conditions of Öcalan,” explained Professor Mesut Yeğen of the Istanbul-based Reform Institute.

“The second expectation is the release of those in poor health who are currently in jail. And for the disarmament process to proceed smoothly, there should be an amnesty or a reduction in sentences, allowing PKK convicts in Turkish prisons to be freed and ensuring that returning PKK militants are not imprisoned,” Yeğen added.

Yeğen claimed that tens of thousands of political prisoners may need to be released, along with the reinstatement of Dem Party mayors who were removed from office under anti-terrorism legislation.

Turkey’s Saturday Mothers keep up vigil for lost relatives

Erdoğan has ruled out any concessions until the PKK disarms, but has said that “good things” will follow disarmament. Meanwhile, the main opposition CHP Party, while welcoming the peace initiative, insists that any democratic reforms directed at the Kurdish minority must be extended to wider society—starting with the release of İmamoğlu, Erdoğan’s chief political rival.

While the peace process is widely seen as a political victory for Erdoğan, it could yet become a liability for the president, who risks being caught between a sceptical voter base and an impatient Kurdish population demanding concessions.

Daily newsletterReceive essential international news every morning Subscribe

Erdoğan’s High-Stakes Gamble on Kurdish Peace

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is making a bold and risky bet on peace with the Kurds. The move follows an unprecedented call from jailed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) leader Abdullah Öcalan for his followers to disarm and disband the militant group. If successful, the move could cement Erdoğan’s political dominance. But past failures and deep-seated tensions cast doubt on its viability.

As Financial Times reports, Öcalan’s appeal comes after four decades of conflict that have claimed 40,000 lives. While his influence over the PKK’s 5,000 fighters remains uncertain, Erdoğan stands to gain politically if the call leads to a negotiated settlement. Pro-Kurdish lawmakers could become crucial allies in Erdoğan’s bid to extend his rule beyond 2028, whether by changing the constitution or calling snap elections.

However, peace efforts have collapsed before. Erdoğan’s last attempt at a political solution in 2015 ended in renewed violence, followed by a military crackdown and mass arrests of Kurdish politicians. Many Kurds demand broader political and cultural rights, raising questions about whether a deal focused solely on PKK disarmament can bring lasting peace.

Beyond domestic politics, Erdoğan is also eyeing regional stability. Turkish-backed forces recently overthrew the Assad regime in Syria, but the U.S.-supported Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), dominated by Kurds and linked to the PKK, remain a major obstacle. A successful peace deal at home could strengthen Erdoğan’s case for persuading Washington to cut support for the SDF.

Despite the cautious optimism, PKK commanders warn that peace will not come quickly, and skepticism remains high among Kurds and political analysts alike. Erdoğan’s willingness to make real concessions is unclear, and failure could lead to renewed conflict. But whether the gamble leads to lasting peace or more violence, one thing is certain—Erdoğan will seek to emerge as the ultimate winner.