New Skhūl I Skull Analysis Could Change Everything We Know About Early Human Evolution

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

New Skhūl I Skull Analysis Could Change Everything We Know About Early Human Evolution

The Skhūl I skull, one of the oldest human burials ever discovered, dates back to 140,000 years ago. For decades, scientists have speculated whether this specimen represents a hybrid of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens or something else entirely. A fresh study analyzed the neurocranial and mandibular features of the fossil using CT scans and 3D modeling. The researchers discovered that the cranial profile and vascular networks of Skhāl I closely resembled those of NeanderTHals. The bony labyrinth, a critical part of the inner ear, was more akin to Homo sapien. Despite these significant findings, the study stops short of making a definitive classification. The skull’s complex mixture of characteristics leaves the researchers without clear answers, and they suggest that Skhál I may best be understood as part of a distinct group. However, as Dr. Anne Malassé points out, no DNA testing has yet been conducted on the Skhaul specimen. Given the rarity and importance of the specimen, destructive testing could compromise its preservation for future generations.

The Skhūl I Skull: A Unique Specimen From Skhūl Cave

Discovered in 1931 at the Skhūl Cave (also known as the Cave of the Children) in Israel’s Carmel Mountains, the Skhūl I fossil has long been a subject of fascination. Initially, it was attributed to a genus called Paleoanthropus palestinensis and considered a transitional form between Neanderthals and modern humans. The fossil is that of a child, aged approximately three to five years old, with a cranial capacity of about 1,100 mL. This suggests a child whose brain size is close to that of modern humans, yet its skeletal structure exhibited features typical of archaic humans.

Archaeologists have debated its classification for years, with some even suggesting the possibility of hybridization between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. This theory stems from the mixture of archaic and modern characteristics found in the skull’s morphology. At one point, the specimen was even thought to be part of a “proto-Cromagnoid” group, though there is still no definitive answer regarding its precise taxonomic placement. Dr. Bouvier’s recent CT scan analysis, however, reveals the fossil’s complex features that blend characteristics of both Neanderthals and modern humans.

Unveiling Hybridization: Skhūl I’s Complex Morphology

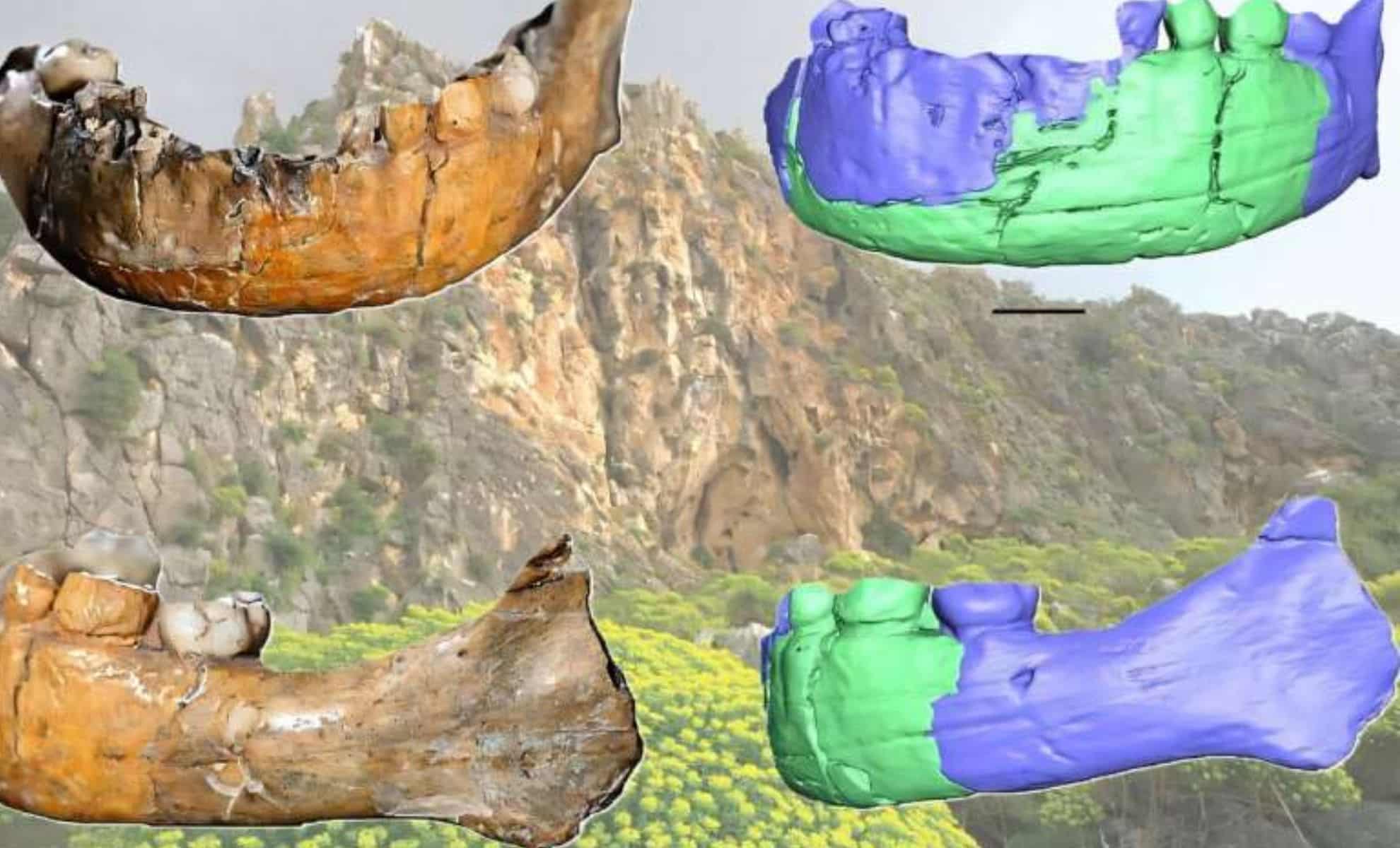

The fresh study analyzed the neurocranial and mandibular features of Skhūl I using CT scans and 3D modeling. These advanced imaging techniques allowed for a clearer understanding of the specimen’s physical characteristics. The researchers discovered that the cranial profile and vascular networks of Skhūl I closely resembled those of Neanderthals, while the bony labyrinth, a critical part of the inner ear, was more akin to Homo sapiens.

External features such as the tilt of the skull base and the positioning of the foramen magnum, the opening where the spine enters the skull, also indicated a greater similarity to Homo sapiens. Dr. Bouvier’s analysis suggests that the tilted position of the foramen magnum aligns with that seen in the Kabwe I specimen of Homo rhodesiensis, a distant relative of modern humans. The mandible, on the other hand, displayed features typical of archaic humans. The backward tilt of the jaw’s inner surface, known as the planum alveolare, is an archaic trait found in several other specimens from the Homo genus, especially from earlier stages of human evolution.

Despite these significant findings, the study stops short of making a definitive classification. The skull’s complex mixture of characteristics leaves the researchers without clear answers, and they suggest that Skhūl I may best be understood as part of a distinct group—potentially a unique “Skhūl paleodeme”—until further evidence, particularly DNA analysis, is available.

The Role of DNA Testing in Solving the Mystery

As the debate continues over the taxonomic classification of Skhūl I, one area that could provide clarity is DNA analysis. However, as Dr. Anne Malassé points out, no DNA testing has yet been conducted on the Skhūl I specimen. “No attempt has ever been made to analyze the DNA of the neurocranium; it is sufficiently preserved to allow the removal of bone from the petrous pyramid. But this is destructive, and the skull is unique,” Dr. Malassé explains. Given the rarity and importance of the specimen, destructive testing could compromise its preservation for future generations of researchers.

The decision to test or not to test the fossil’s DNA remains a difficult one. While advancements in DNA extraction methods make it technically possible, the question of whether to proceed is weighed against the skull’s unique status in the archaeological community. DNA analysis could offer definitive answers about whether Skhūl I was a member of Homo sapiens or a hybrid of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, but for now, the risk of damaging such a rare specimen keeps the issue unresolved.

Cultural Implications: Was Skhūl I Given Special Treatment?

Beyond the biological and taxonomic questions, the burial of Skhūl I also raises intriguing cultural questions. The child was buried in the Skhūl Cave, a site that has yielded several other human remains, including both adults and children. Unlike many prehistoric burials, there is no indication that Skhūl I was given any special treatment prior to or during burial. Dr. Malassé, a key figure in the study, mentions that “the body was compacted a second time, so it is no longer in the primary position to establish comparison, but archaeologists have never observed any special treatment of the body before and during its burial that distinguishes it from other individuals.”

This observation may suggest that early humans practiced group burials without giving preferential treatment to individuals. It also speaks to the social structures of early human groups, where children were likely treated as equals within their communities. The lack of special burial rites for Skhūl I could indicate a more egalitarian society among early humans, but more evidence would be needed to make that determination.

Source: https://indiandefencereview.com/skhul-i-skull-analysis-change-early-human/