Fossil discovery reveals the Grand Canyon was a ‘Goldilocks zone’ for the evolution of early animals

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Fossil discovery reveals the Grand Canyon was a ‘Goldilocks zone’ for the evolution of early animals

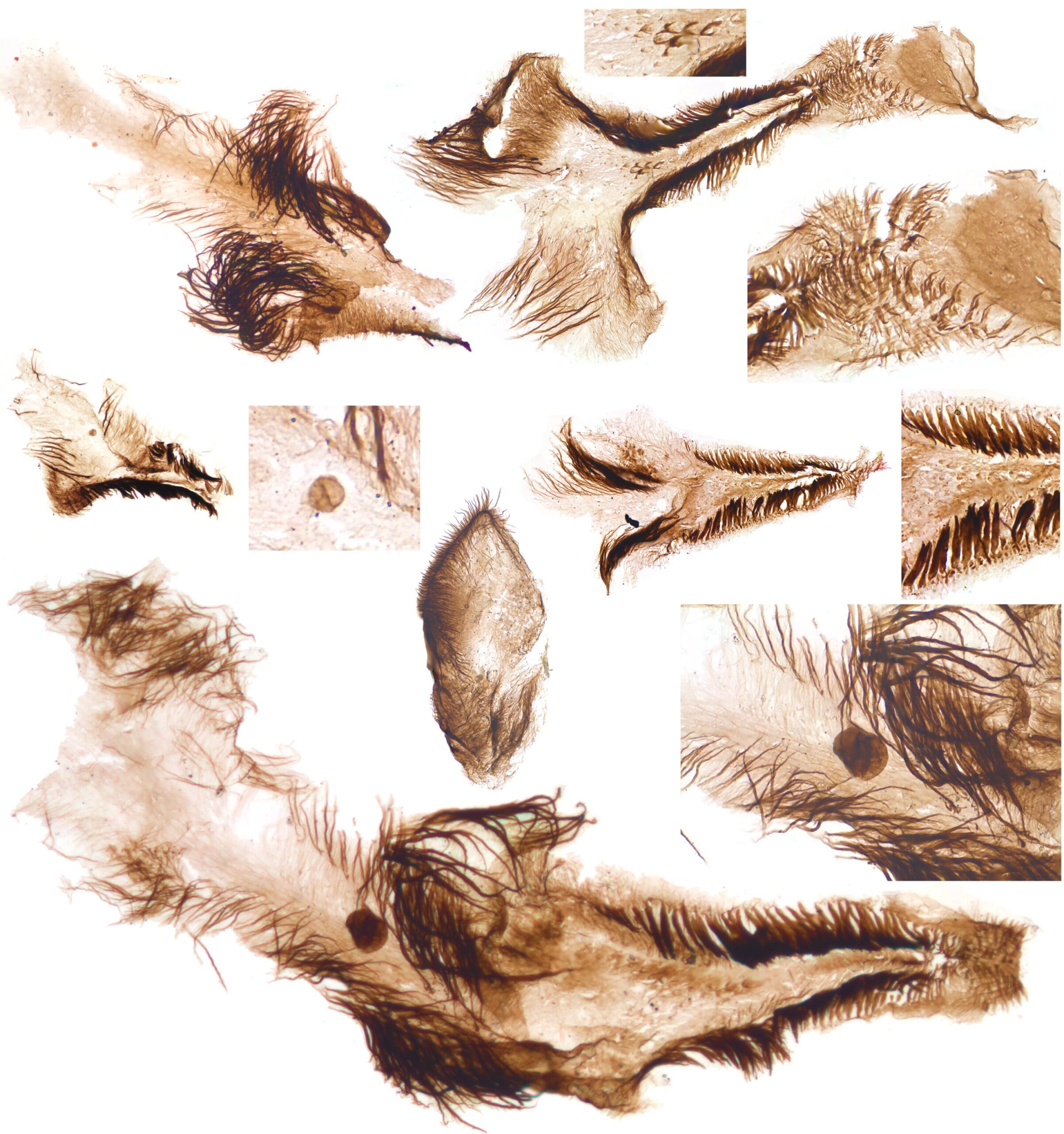

Fossils found in the Grand Canyon include tiny rock-scraping mollusks, filter-feeding crustaceans, spiky-toothed worms, and even fragments of the food they likely ate. The fossilized animals date from between 507 and 502 million years ago, during a period of rapid evolutionary development known as the Cambrian explosion. Researchers led by the University of Cambridge were able to get a highly detailed picture of a unique period in the evolution of life on Earth. They named the fossil Kraytdraco spectatus, after the krayt dragon, a fictional creature from the Star Wars universe, and a new species of priapulids, also known as penis or cactus worms, which were widespread during the Cambririan but are nearly extinct today. It is the first soft-bodied, or non-mineralized, Cambrian fossils from an evolutionary “Goldilocks zone” that would have provided rich resources for animals to accelerate, the researchers said.

A treasure trove of exceptionally preserved early animals from more than half a billion years ago has been discovered in the Grand Canyon, one of the natural world’s most iconic sites. The rich fossil discovery – the first such find in the Grand Canyon – includes tiny rock-scraping molluscs, filter-feeding crustaceans, spiky-toothed worms, and even fragments of the food they likely ate. Credit: Mussini et al.

A treasure trove of exceptionally preserved early animals from more than half a billion years ago has been discovered in the Grand Canyon, one of the natural world’s most iconic sites.

The rich fossil discovery—the first such find in the Grand Canyon—includes tiny rock-scraping mollusks, filter-feeding crustaceans, spiky-toothed worms, and even fragments of the food they likely ate.

By dissolving the rocks these animals were fossilized in and examining them under high-powered microscopes, researchers led by the University of Cambridge were able to get a highly detailed picture of a unique period in the evolution of life on Earth. The results are reported in the journal Science Advances.

The fossilized animals date from between 507 and 502 million years ago, during a period of rapid evolutionary development known as the Cambrian explosion, when most major animal groups first appear in the fossil record.

In some areas during this period, nutrient-rich waters powered an evolutionary arms race, with animals evolving a wide variety of exotic adaptations for food, movement or reproduction.

Most animal fossils from the Cambrian are of hard-shelled creatures, but in a handful of locations around the world, such as Canada’s Burgess Shale formation and China’s Maotianshan Shales, conditions are such that softer body parts could be preserved before they decayed.

So far, however, fossils of non-skeletonized Cambrian animals had been known mostly from oxygen and resource-poor environments, unlikely to kickstart the most complex innovations that shaped early animal evolution.

A new species of priapulids, also known as penis or cactus worms, which were widespread during the Cambrian but are nearly extinct today. The Grand Canyon priapulid had hundreds of complex branching teeth, which helped it sweep food particles into its extensible mouth. Due to the size of the fossil and its exotic rows of teeth, the researchers named this new animal Kraytdraco spectatus, after the krayt dragon, a fictional creature from the Star Wars universe. Credit: Rhydian Evans

Now, the Grand Canyon has revealed the first soft-bodied, or non-mineralized, Cambrian fossils from an evolutionary “Goldilocks zone’ that would have provided rich resources for the evolution of early animals to accelerate.

“These rare fossils give us a fuller picture of what life was like during the Cambrian period,” said first author Giovanni Mussini, a Ph.D. student in Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences.

“By combining these fossils with traces of their burrowing, walking, and feeding—which are found all over the Grand Canyon—we’re able to piece together an entire ancient ecosystem.”

Mussini and colleagues from the US located the fossils during a 2023 expedition along the Colorado River, which began carving the Grand Canyon in what is now Arizona between five and six million years ago.

“Surprisingly, we haven’t had much of a Cambrian fossil record of this kind from the Grand Canyon before—there have been finds of things like trilobites and biomineralized fragments, but not much in the way of soft-bodied creatures,” said Mussini.

“But the geology of the Grand Canyon, which contains lots of fine-grained and easily split mud rocks, suggested to us that it might be just the sort of place where we might be able to find some of these fossils.”

The researchers collected several samples of rock and returned them to Cambridge. The fist-sized rocks were first dissolved in a solution of hydrofluoric acid, and the sediment was passed through multiple sieves, releasing thousands of tiny fossils within. None of the animals were preserved in their entirety, but many recognizable structures helped the researchers identify which groups the animals belonged to.

Further examination of the fossils revealed some of the most complex ways animals were evolving during the Cambrian to capture and eat their food. “These were cutting-edge ‘technologies’ for their time, integrating multiple anatomical parts into high-powered feeding systems,” said Mussini.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights. Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs, innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Many of these fossils are of crustaceans, likely belonging to the group that includes brine shrimp, recognizable by their molar teeth. These tiny creatures had hair-like extensions on triangular grooves around their mouths, and used their hairy limbs to sweep up passing food particles like a conveyer belt.

Tiny grooves on their teeth could then grind up their food. The detail on the fossils is such that several plankton-like particles can be seen near the crustaceans’ mouths.

A treasure trove of exceptionally preserved early animals from more than half a billion years ago has been discovered in the Grand Canyon, one of the natural world’s most iconic sites. Credit: Joe Clevenger

Other modern-looking animals from the Cambrian of the Grand Canyon include slug-like mollusks. These animals already had belts or chains of teeth not dissimilar to modern garden snails, which likely helped them scrape algae or bacteria from rocks.

The most unusual creature identified by the researchers is a new species of priapulids, also known as penis or cactus worms, which were widespread during the Cambrian but are nearly extinct today.

The Grand Canyon priapulid had hundreds of complex branching teeth, which helped it sweep food particles into its extensible mouth. Due to the size of the fossil and its exotic rows of teeth, the researchers named this new animal Kraytdraco spectatus, after the krayt dragon, a fictional creature from the Star Wars universe.

“We can see from these fossils that Cambrian animals had a wide variety of feeding styles used to process their food, some which have modern counterparts, and some that are more exotic,” said Mussini.

During the Cambrian, the Grand Canyon was much closer to the equator than it is today, and conditions were perfect for supporting a wide range of life. The depth of the oxygen-rich water, neither too deep or too shallow, allowed a balance between maximizing nutrients or oxygen and reducing wave damage and exposure to UV radiation from the sun.

This optimum environment made it a great place for evolutionary experimentation. Since food was abundant, animals could afford to take more evolutionary risks to stay ahead of the competition, accelerating the overall pace of evolution and driving the assembly of ecological innovations that still shape the modern biosphere.

“Animals needed to keep ahead of the competition through complex, costly innovations, but the environment allowed them to do that,” said Mussini.

“In a more resource-starved environment, animals can’t afford to make that sort of physiological investment. It’s got certain parallels with economics: invest and take risks in times of abundance; save and be conservative in times of scarcity. There’s a lot we can learn from tiny animals burrowing in the sea floor 500 million years ago.”

More information: Evolutionary escalation in an exceptionally preserved Cambrian biota from the Grand Canyon (Arizona, USA), Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv6383 Journal information: Science Advances

Treasure trove of half-billion-year-old animal fossils found in Grand Canyon

Fossils of some of Earth’s earliest animals have been found in the Grand Canyon. The fossils date to between 507 and 502 million years ago (mya) in the middle of the Cambrian period which lasted from 541 to 485 mya. The Cambrian saw an evolutionary “explosion’ with all the basic body types seen in modern animals first appearing in Earth’s ancient seas during this period. Soft body parts from Cambrian environments tend to be from oxygen- and resource-poor environments which are perfect for rapid fossilisation. Many of the fossils resemble modern-day crustaceans including shrimp. Others are molluscs similar to today’s slugs. The team also identified a new species of ancient priapulid – a group known as penis or cactus worms – which are nearly extinct today. The researchers named the new animal spectatus, after the fictional kraytdraco dragon from the Star Wars universe. It got certain parallels with the conservative economics of early animals.

The fossils date to between 507 and 502 million years ago (mya) in the middle of the Cambrian period which lasted from 541 to 485 mya. The Cambrian saw an evolutionary “explosion” with all the basic body types seen in modern animals first appearing in Earth’s ancient seas during this period.

It’s the first time Cambrian fossils have been found in the Grand Canyon.

Sternal elements of crustaceans from the Cambrian period. Credit: Mussini et al.

The rich deposit, detailed in a paper published in Science Advances, includes tiny, rock-scraping molluscs, filter feeding crustaceans, spiky-toothed worms and possibly fragments of some of the food these ancient creatures ate.

Most Cambrian animals had hard outer shells. Soft body parts have been found in some places around the world, like Canada’s famous Cambrian site the Burgess Shale formation and China’s Maotianshan Shales. Soft body parts from the Cambrian tend to be from oxygen- and resource-poor environments which are perfect for rapid fossilisation.

Grand Canyon. Credit: Joe Clevenger.

The new Grand Canyon discovery, however, includes the world’s first soft-bodied Cambrian fossils from a resource-rich “Goldilocks zone” which would have provided conditions for accelerated evolution of early animals.

During the Cambrian, the Grand Canyon was closer to the equator and had oxygen-rich waters which were neither too deep nor too shallow. They were “just right” for supporting the evolution of early animals.

“These rare fossils give us a fuller picture of what life was like during the Cambrian period,” says first author Giovanni Mussini, a PhD student at the UK’s University of Cambridge. “By combining these fossils with traces of their burrowing, walking, and feeding – which are found all over the Grand Canyon – we’re able to piece together at an entire ancient ecosystem.”

“Surprisingly, we haven’t had much of a Cambrian fossil record of this kind from the Grand Canyon before. There have been finds of things like trilobites and biomineralised fragments, but not much in the way of soft-bodied creatures,” says Mussini. “But the geology of the Grand Canyon, which contains lots of fine-grained and easily split mud rocks, suggested to us that it might be just the sort of place where we might be able to find some of these fossils.”

Mussini and colleagues first dissolved the rock around the fossils using a solution of hydrofluoric acid. The sediment was then passed through sieves to release thousands of tiny fossils.

These were then examined under high-powered microscopes to reveal their features.

Many of the fossils resemble modern-day crustaceans including shrimp. Others are molluscs similar to today’s slugs.

The microscopic analysis revealed many of the complex ways these early animals were evolving to catch and eat their prey.

The crustaceans had hair-like extensions on triangular grooves around their mouths and hairy limbs used to sweep passing food particles into their mouths like a conveyor belt. The molluscs had chains of teeth, like those of a modern garden snail, which they likely used to scrape algae or bacteria off rocks.

“These were cutting-edge ‘technologies’ for their time, integrating multiple anatomical parts into high-powered feeding systems,” Mussini says.

The team also identified a new species of ancient priapulid – a group known as penis or cactus worms. These were widespread during the Cambrian but are nearly extinct today. The Grand Canyon fossil priapulid had hundreds of complex branching teeth which it used to sweep food into its extendible mouth.

The researchers named the new animal Kraytdraco spectatus, after the fictional krayt dragon from the Star Wars universe.

Illustration of the mouth of Kraytdraco spectatus. Credit: Rhydian Evans.

The region during the Grand Canyon was likely a prime location for evolutionary experimentation of early animals.

“Animals needed to keep ahead of the competition through complex, costly innovations, but the environment allowed them to do that,” Mussini explains. “In a more resource-starved environment, animals can’t afford to make that sort of physiological investment. It’s got certain parallels with economics: invest and take risks in times of abundance; save and be conservative in times of scarcity. There’s a lot we can learn from tiny animals burrowing in the sea floor 500 mya.”

Source: https://phys.org/news/2025-07-fossil-discovery-reveals-grand-canyon.html