The hidden reason why certain lifestyle choices make others uncomfortable

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

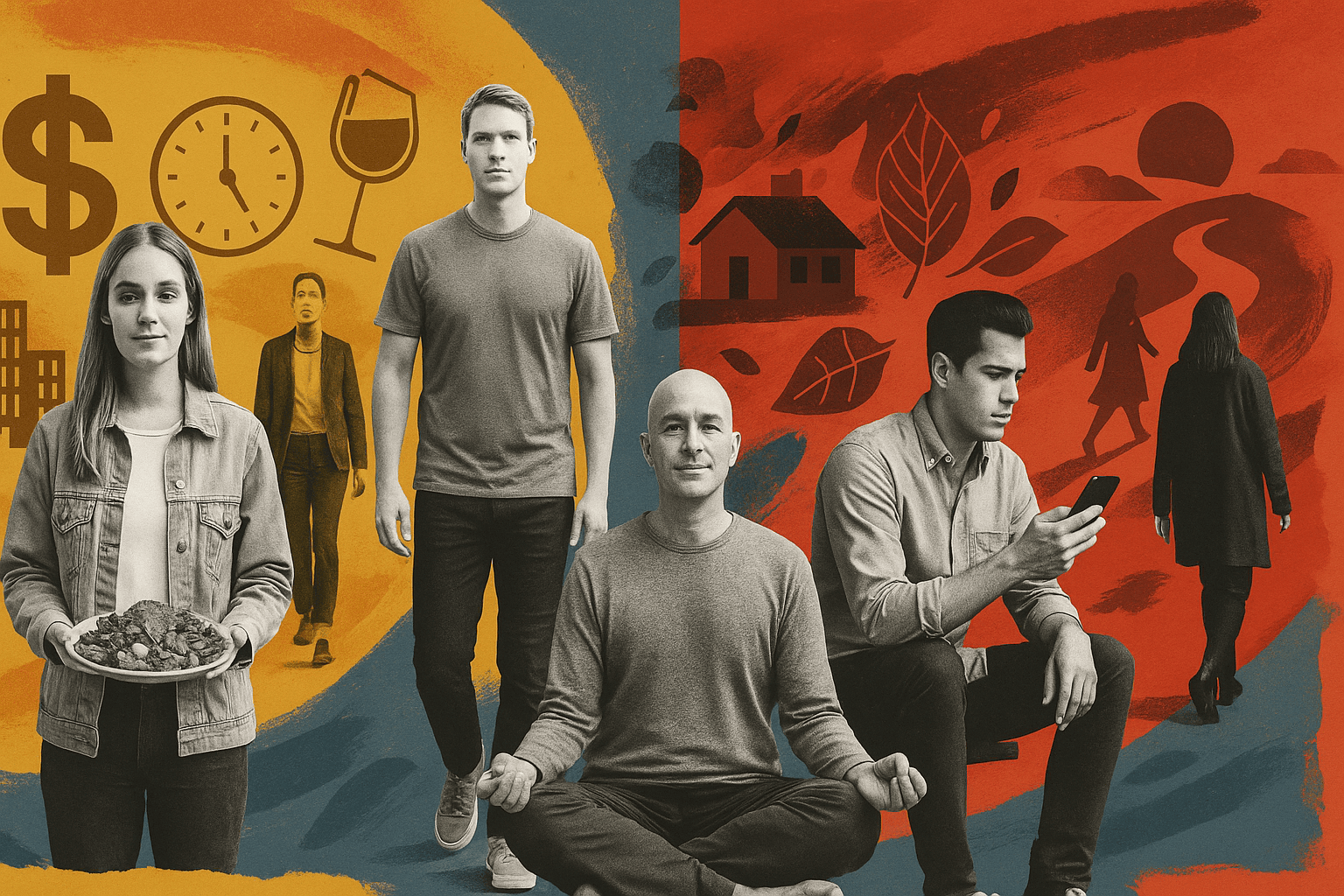

The hidden reason why certain lifestyle choices make others uncomfortable

Vegans are a perfect example. They don’t have to be preachy or even vocal about their choices. They can just show up, order their plant-based meal, and suddenly the table changes. Their choice to live outside a dominant norm pulls invisible threads loose. These are symbolic rejections of what many people believe defines a “good life.” And that can feel threatening. Because if you’re not doing these things out of scarcity or trauma, then your existence raises an unspoken question: What if the life I’ve built isn’ts based on freedom, but on conformity? And that’s not a question most people want to ask over lunch. It happens structurally.Society rewards certain choices because they’ll keep the system running. And when you deviate, even quietly, you reveal how much of our so-called “freedom” is shaped by invisible incentives. This is why someone who decides to upgrade their phone for ten years can seem suspicious.

Vegans are a perfect example. They don’t have to be preachy or even vocal about their choices. They can just show up, order their plant-based meal, and suddenly the table changes. People get nervous. Jokes appear. Someone brings up bacon. Another confesses they “tried oat milk once” as if making amends.

It’s rarely about the vegan. It’s about the people around them.

I’ve always admired vegans for this reason—not just because of their ethics or clarity, which I wrote about recently—but because of the strange, involuntary effect they have on others. They unintentionally trigger people. Their choice to live outside a dominant norm pulls invisible threads loose.

And that’s what this article is really about.

Why do certain lifestyle choices—veganism, sobriety, minimalism, not wanting kids, not owning a smartphone—make people uncomfortable? Not just confused, but defensive? Even hostile?

It’s not because those choices are extreme. It’s because they quietly interrupt the social script.

Most people live by a kind of tacit agreement. A consensus reality. We agree not to challenge certain assumptions in public—especially the ones we haven’t examined ourselves. And when someone lives in open contradiction to those assumptions, it feels like a breach of contract.

Take alcohol. A sober person at a party doesn’t need to say a thing. Their refusal to drink can be enough to make others uncomfortable. People start justifying their own consumption, offering explanations nobody asked for. The sober person hasn’t accused anyone of anything—but their choice destabilizes the collective agreement: This is what we do. This is who we are. This is normal.

Veganism does the same thing. So does choosing not to buy a house. Or walking away from a six-figure career. Or deciding not to have children.

These are not just personal choices. In the eyes of others, they are symbolic rejections—rejections of what many people believe defines a “good life.” And that can feel threatening.

Because if you’re not doing these things out of scarcity or trauma—if you’re genuinely content, even thriving—then your existence raises an unspoken question:

What if the life I’ve built isn’t based on freedom, but on conformity?

And that’s not a question most people want to ask over lunch.

We’re social creatures. We build our identities not in isolation, but through reflection—through the stories we’re surrounded by. And when someone stops participating in a shared story, we don’t just see them as “different.” We start to feel judged, even when no judgment is being offered.

It’s projection.

We assume they must think we’re doing it wrong—because on some level, we’re afraid they might be right.

Of course, that fear is almost never voiced. It disguises itself as mockery. Disbelief. Passive-aggression. The “come on, live a little” jokes. The exaggerated concern. The forced neutrality. Sometimes even moral outrage.

Because the human psyche doesn’t like dissonance. When someone lives in a way that doesn’t match our map of how the world works, we either have to revise the map—or discredit them. And it’s always easier to discredit the person.

So we call them extreme. Or unrealistic. Or naive. We accuse them of being rigid or self-righteous, even when they’re being completely silent.

Because if they’re not wrong, we might have to change something.

And change—especially internal, value-level change—is much harder than laughing something off.

This discomfort doesn’t just happen in isolated moments. It happens structurally.

Society rewards certain choices. Not because they’re universally good, but because they keep the system running. Consumption, ambition, productivity, family formation—these are the levers of the economic engine. And when you deviate, even quietly, you reveal how much of our so-called “freedom” is shaped by invisible incentives.

This is why someone who decides not to upgrade their phone for ten years can seem suspicious. Or someone who lives alone and doesn’t long for partnership. Or someone who works just enough to meet their needs and chooses not to hustle for more. These people aren’t just opting out of behaviors—they’re rejecting beliefs. Beliefs so deeply normalized that most of us don’t realize we’ve internalized them.

And that’s what makes the discomfort so hard to name. It’s not about disagreement—it’s about rupture. A break in the collective illusion that we all want the same things.

When someone says no to what you’ve built your life around, it can feel like a rejection of you. Even when it isn’t.

I’ve felt this myself—on both sides.

I’ve made decisions that made people squirm. Walking away from traditional work. Choosing minimalism at a time when my peers were acquiring. Living alone in countries people didn’t understand. At first, I thought the discomfort was about me—that I wasn’t explaining myself well enough, or that I’d gone too far.

But over time, I realized it wasn’t personal. It was existential.

I had stopped reflecting back the world they were trying to make sense of.

And I’ve also felt discomfort when others made choices I hadn’t been brave enough to consider. A friend who decided never to marry. Another who sold everything to live off-grid. A woman who chose not to have children and talked about it openly. I noticed my own micro-reactions—little surges of defensiveness, disbelief, maybe even judgment. But behind them was something else: a subtle panic that my own choices might not have been as free as I thought.

That’s the real discomfort.

It’s not about ethics or superiority. It’s about autonomy. About the fear that we’ve traded freedom for approval, and someone else’s freedom is making that trade visible.

Most of us were taught that discomfort is a cue to escape. But in moments like these, it’s actually a signal. A sign that something hidden is brushing up against the surface. Not a threat—but a prompt.

And if we’re willing to stay with that discomfort, to not swat it away with cynicism or sarcasm, we might find something useful in it. Something liberating.

Because the discomfort is rarely about the other person. It’s about the places in ourselves where we haven’t looked closely enough.

It’s about the stories we inherited but never edited.

The values we perform but never chose.

The fears we suppress beneath our “normal” lives.

That’s why certain lifestyle choices feel so destabilizing: not because they challenge what’s right or wrong, but because they challenge what’s normal. And “normal” is the most defended concept in modern life. It’s where belonging lives. Where identity hides. Where expectations root themselves so deeply we can’t see them anymore.

So when someone lives outside of normal, we either pull them back in—or exile them.

But here’s the twist: the people who trigger us most are often the ones showing us something valuable.

Not because they’re right and we’re wrong. But because their choices illuminate the parts of ourselves we’ve gone numb to—the parts we traded away for safety, or ease, or fitting in. Sometimes they remind us of who we used to be. Or who we secretly want to become.

I think that’s why I’ve always found myself quietly drawn to people who make others uncomfortable. Not the loud provocateurs—but the ones who live their lives with quiet defiance. People who opt out of default scripts without making a show of it. People who carry an unusual calm, like they’re not in the same race as the rest of us.

Vegans, again, are just one example. It’s not the diet I admire. It’s the courage to live with conviction in a world that constantly pressures us to compromise. They show how a personal decision can ripple outward. How just living your values, visibly and unapologetically, becomes a kind of mirror—one others may not like, but might need.

The same goes for the minimalist, the child-free couple, the early retiree, the woman who chooses solitude over romance, the man who walks away from status to recover his health or peace of mind. They’re all doing the same thing: reminding us that there are other ways to live. That the defaults aren’t destiny.

And that’s the gift hidden inside discomfort—if we choose to receive it.

Instead of flinching or mocking, we can pause. Get curious. Ask why this bothers us so much. What belief is being challenged? What part of us is feeling exposed?

Because discomfort isn’t always a sign that something’s wrong. Sometimes it’s a sign that something is waking up.

That a part of us is hungry for a life that’s more honest, more spacious, more ours.

In a way, the people who trigger us are inviting us—not to copy them, but to examine ourselves. To ask whether the life we’ve constructed is one we truly chose—or one we inherited, downloaded, performed.

That question isn’t easy. It can dismantle things.

But it’s the kind of question that leads to freedom.

And maybe that’s why these choices make people uncomfortable. Because they threaten the illusion that there is only one way to live a good life. That if we just follow the map, we’ll end up somewhere meaningful.

But some people burn the map. Not to rebel. Not to shock. Just because they realized it was never theirs to begin with.