Health Rounds: Weight-loss surgery more effective than drugs in real world study

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Health Rounds: Weight-loss surgery more effective than drugs in real world study

Bariatric surgeries led to about five-times more weight loss than weekly injections of popular GLP-1 drugs. A blood test can help surgeons catch and identify problems with newly transplanted livers at early stages, researchers say.Ultrasound exams of thigh or shoulder muscles can detect insulin resistance at its earliest stages, according to a new study. The study was presented on Tuesday at the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery scientific meeting in Washington, D.C. It’s not unusual for transplanted organs and recipients’ nearby tissues to sustain damage during the transplantation process, but identifying the precise site of the damage often requires costly imaging studies and surgical biopsies, the researchers said in a report. The new test works by picking up DNA fragments left behind in the blood by dying cells and can be used to identify the original cell type and where it came from, with precise detail, they said. It has filed patent applications on the technology and the research team is seeking partners to commercialize the test.

June 18 (Reuters) – (This is an excerpt of the Health Rounds newsletter, where we present latest medical studies on Tuesdays and Thursdays. To receive the full newsletter in your inbox for free sign up here .)

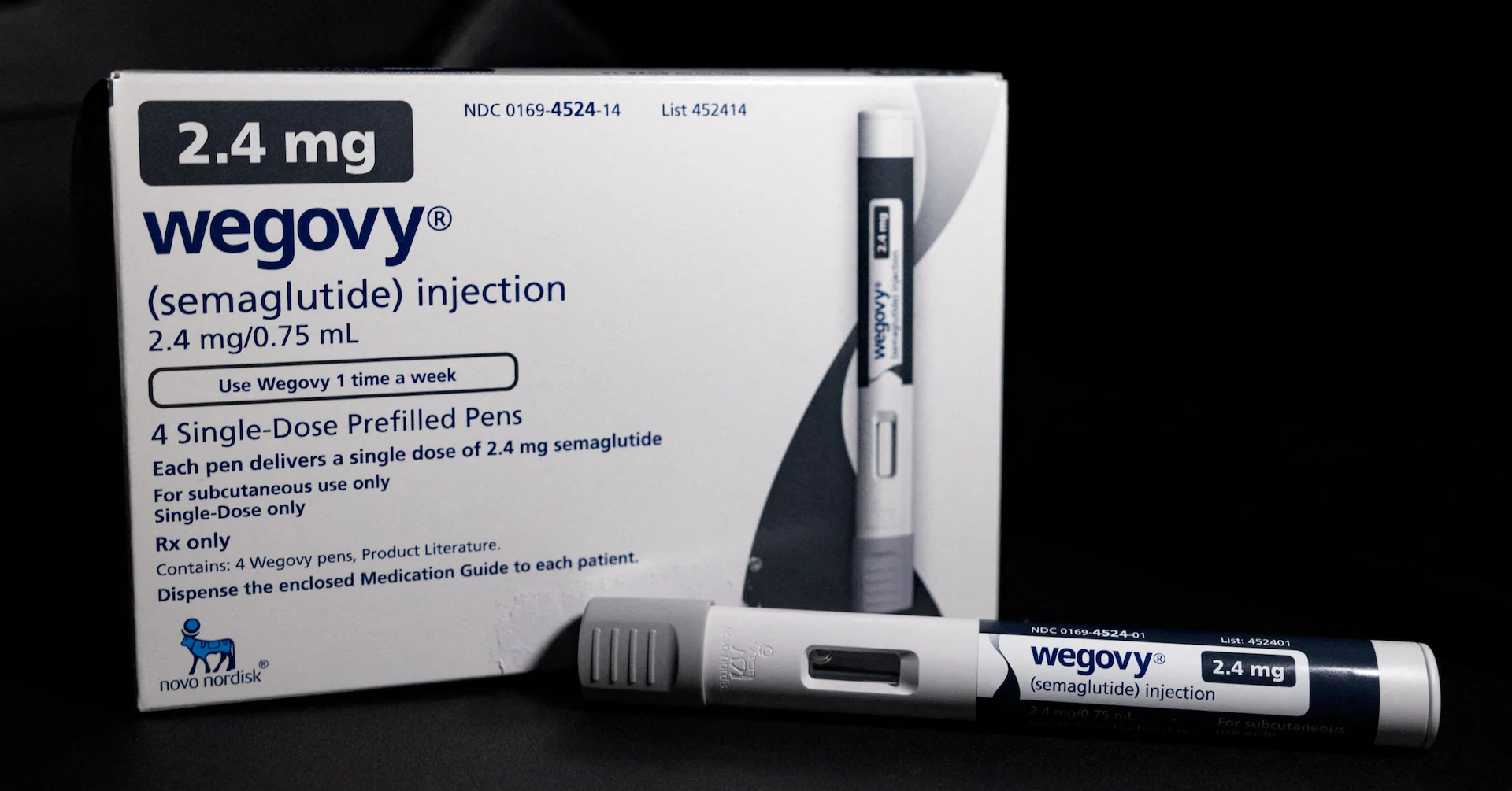

Bariatric surgeries led to about five-times more weight loss than weekly injections of popular GLP-1 drugs, according to data from a real-world comparison study presented on Tuesday at the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery scientific meeting , opens new tab in Washington.

Sign up here.

“Clinical trials show weight loss between 15% to 21% for GLP-1s, but this study suggests that weight loss in the real world is considerably lower even for patients who have active prescriptions for an entire year,” study leader Dr. Avery Brown of NYU Langone Health said in a statement.

Researchers reviewed records of 38,545 patients who were prescribed injectable semaglutide or tirzepatide between 2018 and 2024 and 12,540 patients who underwent bariatric surgery during the same period. Everyone started the study with a body mass index of at least 35, which is considered severe obesity.

At three years after undergoing sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass or starting the drugs, patients who underwent surgery had lost on average 24% of their starting weight, compared to about 5% for similar patients who used the drugs for at least six months and about 7% for those who took them for a year.

Brown noted that as many as 70% of GLP-1 patients may discontinue treatment within one year.

“While both patient groups lose weight, metabolic and bariatric surgery is much more effective and durable,” ASMBS President Dr. Ann M. Rogers, who was not involved in the study, said in a statement.

“Those who get insufficient weight loss with GLP-1s or have challenges complying with treatment due to side effects or costs, should consider bariatric surgery as an option, or even in combination,” she said.

NEW BLOOD TEST MAY REDUCE LIVER TRANSPLANT FAILURES

An experimental blood test can help surgeons catch and identify problems with newly transplanted livers at early stages, researchers say.

It’s not unusual for transplanted organs and recipients’ nearby tissues to sustain damage during the transplantation process. Hints of problems will show up later in routine blood tests, but identifying the precise site of the damage often requires costly imaging studies and surgical biopsies, according to a report published on Tuesday in Nature Communications , opens new tab

The new test works by picking up DNA fragments left behind in the blood by dying cells. The chemical signatures on these DNA fragments can be used to identify the original cell type and where it came from, with precise detail, the researchers found.

If you can determine which part of the liver is injured – for example, the bile ducts, or the blood vessels – “you could provide a more personalized treatment approach that leads to better care for the patient,” study leader Dr. Alexander Kroemer of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, DC said in a statement.

In addition to being faster and less invasive than a traditional biopsy, the blood test is also potentially more accurate, because biopsies only sample a few spots in the liver and might miss the site of the problem, he added.

Georgetown has filed patent applications on the technology, and the research team is seeking partners to commercialize the test.

DIABETES PRECURSOR SHOWS UP ON MUSCLE ULTRASOUND

Ultrasound exams of thigh or shoulder muscles can detect insulin resistance at its earliest stages, researchers reported in the Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine , opens new tab

“We perform a large number of shoulder ultrasounds and noticed that many patients’ muscles appear unusually bright,” study leader Dr. Steve Soliman of the University of Michigan said in a statement.

His team discovered in earlier studies that most of these patients have type 2 diabetes. But some had bright muscles on ultrasound even with no signs of diabetes or prediabetes.

Subsequently, upon short-term follow-up, these patients often also developed prediabetes or type 2 diabetes.

To test the potential for noninvasive muscle ultrasound as a predictive tool for detecting the development of pre- or type 2 diabetes – potentially earlier than current methods – the researchers performed muscle ultrasounds on 25 patients who were also being evaluated for insulin resistance.

Although muscle ultrasound could detect insulin resistance and impaired insulin sensitivity, in this small study the level of brightness was not directly correlated with the degree of the condition. The researchers are recruiting more participants to continue the analysis.

The exact reason why muscle brightness on ultrasound might indicate insulin resistance is less clear than the finding that it does, the researchers said.

“Clinicians increasingly use these point-of-care and handheld ultrasound devices, sometimes called ‘the stethoscope of the future,’ for rapid diagnosis of various conditions,” Soliman said.

“A medical assistant or clinician with little to no training could easily use this device on a patient’s upper arm or thigh, as routinely as checking weight or blood pressure, and potentially flag patients as ‘high risk’ or ‘low risk’ for further testing.”

(To receive the full newsletter in your inbox for free sign up here

Reporting by Nancy Lapid; editing by Bill Berkrot

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Share X

Link Purchase Licensing Rights