Mapping local economic consequences of federal cuts to NIH: How they did it

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Mapping local economic consequences of federal cuts to NIH: How they did it

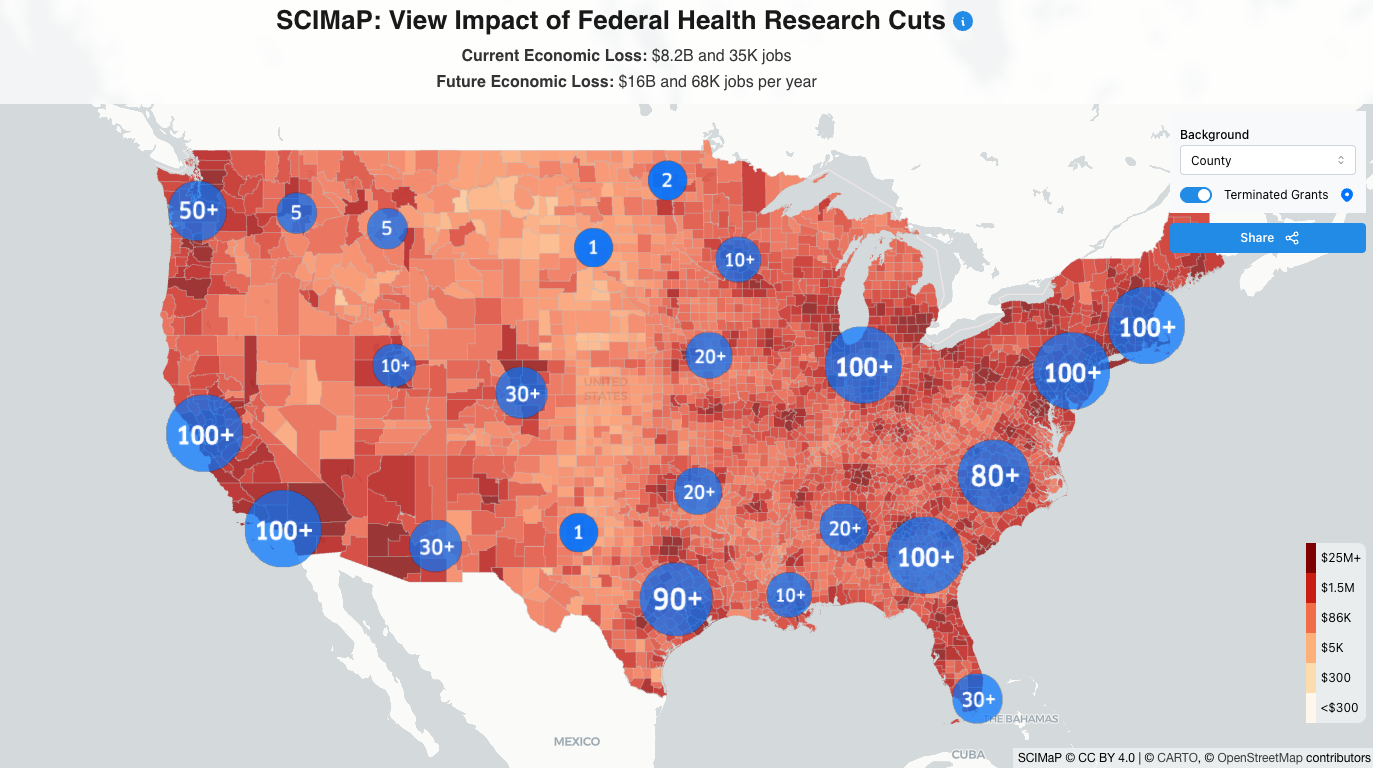

Alyssa Sinclair and Joshua Weitz released a map showing the impact of federal health research cuts. The map shows the state-by-state, district- by-district, and county-By-county level impacts of cutting funding for operating costs at NIH-funded facilities across the United States. The interactive map also includes a quiz that gauges what people expect the scale of impacts in their area before they see the map. AHCJ spoke to Sinclair and Weitz in April about how they quickly organized the mapping project and their future plans for it amid this rapidly developing national story with myriad local effects. Back to Mail Online home.Back to the page you came from. The article was originally published on June 18, 2025. It was updated on June 17, 2025, to include the interactive map and an interactive quiz on the website that gauged what people expected the scale to be before they saw the map and the corresponding number of jobs lost. For confidential support, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or visit www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

As the federal cuts to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other science institutions began to unfold in January and February, communications researcher Alyssa Sinclair, Ph.D., and health data expert Joshua Weitz, Ph.D., immediately saw the need for information about local economic effects.

The two interdisciplinary researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Maryland, respectively, began collaborating during the COVID-19 pandemic when researching public health communications best practices. Both saw a need to apply their experience during yet another national crisis.

On March 27, the duo and their colleagues released a map showing the state-by-state, district-by-district, and county-by-county level impacts of cutting funding for operating costs at NIH-funded facilities across the United States.

Sinclair and Weitz spoke to AHCJ in April about how they quickly organized the mapping project and their future plans for it amid this rapidly developing national story with myriad local effects.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

How did this mapping project come about?

Sinclair: Years ago, Joshua and I had collaborated on a number of projects that were related to the COVID pandemic, developing free and accessible public-facing websites to help people understand exposure risk in their local communities. We wanted to relate abstract information about risk to everyday scenarios. Joshua reached out to me and said, “What if we did something similar for this moment to help people understand the local current impacts that would result from these changes to federal funding for science?”

I was immediately very excited. It seemed like a great opportunity to do outreach and communication that could reach a much broader audience. We saw an opportunity to present this local, self-relevant information to a lot of people, to bring this issue to the foreground.

Weitz: In early February [February 10] the NIH implemented supplementary guidance that said that the indirect cost rate that supports infrastructure for medical research nationwide was going to be drastically cut, slashed by more than half to 15%, effective immediately. In plain terms, that meant that, if implemented, the costs that go into supporting medical research across a broad range of topics would no longer be there. And that means slowing and halting programs, scientists losing jobs and projects being stopped. So, at that moment I was very concerned that this would have ripple effects.

After a few weeks, it became clear to me that the communication of these effects was not quite getting through. It seemed arcane, difficult to understand and also not focused on the level that I thought was going to really matter: the local level.

By early March, I thought there was a place for scientists to communicate these cuts, not necessarily as impacts to science, scientists and their institutions but rather to communities all across America — not just big cities or major private institutions, but also public and private universities, hospitals and research institutes. At that point, I proposed to Alyssa that we visualize and communicate these cuts, not just in terms of individual one-off stories, but through a map.

How did you go about making the map? What does it show?

Weitz: Right now, the map on scienceimpacts.org describes the consequences of reductions in research infrastructure support, called indirect costs — the costs associated with facilities, compliance and safety checks that are pulled from and shared across many projects and are vital to do the research. And so, this maps out the consequences on a grant level.

Each grant has direct and indirect costs. It’s the indirect costs that are [potentially] being reduced. [Some grants’ direct costs are also being cut.] We take all data from the NIH-awarded grants in fiscal year 2024, estimate the impact that would be on a grant level, pool those based on location to the relevant counties, and then take into account the effect that people don’t necessarily all live where they work and may commute. And so, the impacts economically flow outwards into nearby communities.

We are showing a loss in economic activity based on estimates that for every, let’s say, $1 million of NIH funding, around $2.5 million of economic activity is supported, along with a corresponding number of jobs. So we take that information from the United for Medical Research coalition, which did that economic study, as a means to project at a national scale.

You have an interactive quiz on the website that gauges what people expect the scale of impacts in their area to be before they see the answer. Why include a quiz?

Sinclair: The design, the features, and the text on the website are heavily informed by what we know from psychology, neuroscience and communication science about what makes people want to engage with information. What makes it memorable? What helps change attitudes and beliefs? For example, we know that self-relevant information — showing people their local communities — and interactive components that elicit surprise can really help people engage with information, share it with other people and remember it.

What kind of response have you seen to the map so far?

Sinclair: In the first week, we had over 50,000 visitors to the website, just from our posting on social media, which I think attests to the general public interest in this tool. We have been meeting with a number of reporters at other news outlets, including data desks and people who do local as well as national reporting on health, science funding and other topics more broadly. So, it’s great to see that there’s been pretty broad interest, and I think this tool is accessible and interpretable for general public members but is also useful for people who are reporters and want to do a deep dive into the data and then create their visualizations.

We’re seeing people zooming in to their local area, taking a screenshot of the economic losses for their region, and then posting that. Some of them are even tagging their Congressional representatives, their local politicians, or community members, to directly send this information to the people who can do something about it, emphasizing the local impact. I think that’s a unique feature and affordance of our tool. And I’m excited to see that people are engaging with it in that way.

What are the limitations of your approach?

Weitz: We aim to be transparent with respect to methods and data. This takes publicly accessible data: how much direct and indirect costs are reported. So, we’re limited by the reports that we or anyone can access from the NIH. With that in mind, these are relatively constant year by year.

The estimate of economic activity and jobs loss is based on an overall analysis. And we take that national analysis and apply it at state and county levels. It’s a limitation, but it’s obviously hard to go into that level of granularity.

And the commuter flows do change with time. In some places, these commuter flows are not as well defined as we would like, even though they’re coming from the U.S. Census, and we probably will update a few locales. We will include that change on the website, documenting updates as we go. I don’t think it’ll lead to major changes, but it will lead to some slight variations moving forward.

Sinclair: We’re being open with our methods, data, and code, and pointing to the public databases that we’re drawing the data from so that anyone could go back and check what particular grants affected their region.

It’s great that someone can look at the grants in their region, and then potentially interview the people who had that grant.

Sinclair: One feature that we hope to add to the website in the future, too, would be a way for people to, say, click on their county and view the top five institutions, for example, that are sort of driving that economic support — or in this case losses. [Note: This feature is now available.]

The news about this situation is constantly changing and updating. How are you handling that?

Sinclair: This is very much a living project. What we’re showing currently is the tip of the iceberg. There have been thousands of direct terminations of grants that were already ongoing that had funds that had yet to be spent. We are currently working on adding those losses to the map. [These losses are now added and updated regularly with new information on grant terminations.] There are other changes as well — for example, losses through other agencies, losses of intramural NIH jobs and research funds, and a proposed reduction of the NSF’s operating budget by about 66%. In the future, we aim to add other metrics of impact to our map. But currently, we’re focusing on those NIH indirect rates.

Weitz: The terminated grants, which have a significant impact, are ongoing. This is unfortunately a dynamic situation, and at some point, we will have to communicate to people that their status is changing. The indirect cost cuts were temporarily and then permanently enjoined. So right now they are not in effect, but the Trump Administration has appealed. There are many kinds of cuts. We are continuing to track them and will release new layers and maps.

The map describes a consequence if this procedure is allowed to go forward — but it has not yet happened.

Even though the cuts aren’t happening yet, local areas could already see effects from the budgetary threats in the health research sector, right?

Sinclair: One thing that I’d like to emphasize is that even though these proposed losses that would result from the indirect cost rate change have been blocked by a judge for now — although we’ll see what happens with this appeal process — simply the threat of these losses in conjunction with the other direct termination of grants has already resulted in widespread erosion of scientific infrastructure, losses of jobs, and losses of training and opportunities for graduate students. We are already feeling the effects, despite the fact that the specific losses that we’re plotting on the map are projections of what would happen if this policy were to take place — and it has not yet been enacted.

Are you planning any other additions to the map?

Weitz: The next one that we hope to be releasing soon has to do with terminated grants related to NIH-funded research. [This is now available.] There are many reasons for these terminations, and there are also lawsuits that are trying to hold back their consequences. And so, in those cases, that’s work that was funded, was approved, and has significant funds left that have not yet been spent. There’s a kind of a double whammy there. You’ve made an investment. You’ve started a project, and not only has your future spending been stopped, but some of your design may require that the project continue. So, we may be wasting money that has already been spent on science and progress. I view that as one of our primary next targets. And then we want to provide information on the thematic consequences, meaning consequences to areas of medical research that are relevant to Americans—things like research for cancer treatment and prevention, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, and diabetes.

Have you received any feedback or interest from economists?

I think there’s some complementarity to what we’re doing and what some economists are doing. There’s a recent piece on the NBER preprint server looking at the history of effective indirect cost rates. The authors argue that these rates are fairly representative. Across multiple administrations, this is how people understand medical and public health research is done in this country. The authors also dispel some myths about what these indirect cost rates are. There is first a negotiated rate between the university and the federal government — these are contracts and grants that are awarded with terms. All of a sudden, now, the terms are gone, and you’ve already baked in these costs in how you’re going to run the research program.

For every, let’s say, $1 million of what are called direct costs — the people, materials, supplies, equipment — the indirect cost rate at some universities can be on the order of 55 to 60%. The effective rate when this group did this analysis was about 42%. So if you look at the total sum that starts to become a more reasonable number, it’s also representative of real costs. Economists have tried to point out that the nominal rates are higher than the effective rates. The effective rates are relatively constant and are representative. And therefore this proposal [to cut indirect costs to 15%] would basically slash things more than in half. It would represent a significant cut that would lead to real economic impacts, as we show, not just to the universities but to economic activity in regions. While economists we’ve talked to have been focusing on the institutional layer, we have been focusing on the geographic nature.