A coal miner’s daughter takes on DOGE to protect miners’ health

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Trump administration blocked from cutting local health funding for four municipalities

A federal court has temporarily blocked the Trump administration from clawing back millions in public health funding from four Democrat-led municipalities in GOP-governed states. The decision means the federal government must reinstate funding to the four municipalities until the case is fully litigated. Their lawsuit alleged $11 billion in cuts to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention programs had already been approved by Congress and are being unconstitutionally withheld. The local governments, alongside the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees union, wanted the court to reinstate the grants nationwide. The federal government’s lawyers said the grants were legally cut because, “Now that the pandemic is over, the grants and cooperative agreements are no longer necessary”

It’s the second such federal ruling to reinstate public health funding for several states.

U.S. District Judge Christopher Cooper in Washington, D.C., issued a preliminary injunction Tuesday sought by district attorneys in Harris County, Texas, home to Houston, and three cities: Columbus, Ohio, Nashville, Tennessee, and Kansas City, Missouri. The decision means the federal government must reinstate funding to the four municipalities until the case is fully litigated.

Their lawsuit, filed in late April, alleged $11 billion in cuts to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention programs had already been approved by Congress and are being unconstitutionally withheld. They also argued that the administration’s actions violate Department of Health and Human Services regulations.

The cities and counties argued the cuts were “a massive blow to U.S. public health at a time where state and local public health departments need to address burgeoning infectious diseases and chronic illnesses, like the measles, bird flu, and mpox.” The cuts would lead to thousands of state and local public health employees being fired, the lawsuit argued.

The local governments, alongside the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees union, wanted the court to reinstate the grants nationwide. But Cooper said in his preliminary injunction that the funds can only be blocked to the four municipalities and in a May 21 hearing expressed skepticism about whether it could apply more widely.

The funding in question was granted during the COVID-19 pandemic but aimed at building up public health infrastructure overall, Harris County Attorney Christian Menefee said in a statement in April.

The four local governments were owed about $32.7 million in future grant payments, Cooper’s opinion notes.

The federal government’s lawyers said the grants were legally cut because, “Now that the pandemic is over, the grants and cooperative agreements are no longer necessary as their limited purpose has run out.” They used the same argument in the case brought by 23 states and the District of Columbia over the HHS funding clawback.

Menefee said the cuts defunded programs in Harris County for wastewater disease surveillance, community health workers and clinics and call centers that helped people get vaccinated. Columbus City Attorney Zach Klein said the cuts forced the city to fire 11 of its 22 infectious disease staffers.

Nashville used some of its grant money to support programs, including a “strike team” that after the pandemic addressed gaps in health services that kept kids from being able to enroll in school, according to the lawsuit.

Kansas City used one of its grants to build out capabilities to test locally for COVID-19, influenza and measles rather than waiting for results from the county lab. The suit details that after four years of work to certify facilities and train staff, the city “was at the final step” of buying lab equipment when the grant was canceled.

Representatives for HHS, the CDC, the cities and Harris County did not immediately respond to requests for comment Tuesday.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Mine safety offices saved from closure

The Mine Safety and Health Administration had been on the chopping block. Ending the leases had been projected to save $18 million. Some MSHA offices are still listed on the DOGE website, but the statement did not indicate whether those closings will move forward. “That’s a relief and good news for miners and the inspectors at MSHA,” says Jack Spadaro, a longtime mine safety investigator and environmental specialist. “We’re going to keep making progress and do whatever it takes to protect coal miners,” says Vonda Robinson, of the National Black Lung Association. health and safety advocates are also trying to save hundreds of jobs within the National Institute for Occupational Health and Health.. Some estimates had about 850 of the agency’s roughly 1,000 employees being cut by the Trump administration.

Earlier this year, the Department of Government Efficiency, created by President Donald Trump and run by Elon Musk, had targeted federal agencies for spending cuts, including terminating leases for three dozen MSHA offices. Seven of those offices were in Kentucky alone. Ending the MSHA leases had been projected to save $18 million.

Musk said this week that he’s leaving his job as a senior adviser.

A statement released by a Labor Department spokesperson Thursday said it has been working closely with the General Services Administration “to ensure our MSHA inspectors have the resources they need to carry out their core mission to prevent death, illness, and injury from mining and promote safe and healthy workplaces for American miners.”

Some MSHA offices are still listed on the chopping block on the DOGE website, but the statement did not indicate whether those closings will move forward.

MSHA was created by Congress within the Labor Department in 1978, in part because state inspectors were seen as too close to the industry to force coal companies to take the sometimes costly steps necessary to protect miners. MSHA is required to inspect each underground mine quarterly and each surface mine twice a year.

“That’s a relief and good news for miners and the inspectors at MSHA,” said Jack Spadaro, a longtime mine safety investigator and environmental specialist who worked for the agency.

Mining fatalities over the past four decades have dropped significantly, in large part because of the dramatic decline in coal production. But the proposed DOGE cuts would have required MSHA inspectors to travel farther to get to a mine.

“I don’t know what they were thinking when they talked about closing offices,” Spadaro said. “They obviously did not understand the nature of the frequency and depth of inspections that go on in mines. It’s important for the inspectors to be near the mine operations that they’re inspecting.”

A review in March of publicly available data by the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center indicates that nearly 17,000 health and safety inspections were conducted from the beginning of 2024 through February 2025 by staff at MSHA offices in the facilities on the chopping block. MSHA, which also oversees metal and nonmetal mines, already was understaffed. Over the past decade, it has seen a 27% reduction in total staff, including 30% of enforcement staff in general and 50% of enforcement staff for coal mines, the law center said.

Coal industry advocates are also trying to save hundreds of jobs within the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Some estimates had about 850 of the agency’s roughly 1,000 employees being cut by the Trump administration.

Earlier this month, a federal judge ordered the restoration of a health monitoring program for coal miners and rescinded layoffs within NIOSH’s respiratory health division in Morgantown, W.Va. The division is responsible for screening and reviewing medical exams to determine whether there is evidence that coal miners have developed a respiratory ailment, commonly known as black lung disease.

At a May 14 Congressional hearing, U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said he was reversing the firing of about 330 NIOSH workers. That same day, the United Mine Workers of America was among several groups that filed a lawsuit seeking to reinstate all NIOSH staff and functions.

“For months, coal communities have been raising the alarm about how cuts to MSHA and NIOSH would be disastrous for our miners,” said Vonda Robinson, vice president of the National Black Lung Association. “We’re glad that the administration has listened and restored these offices, keeping mine inspectors in place.”

“We’re going to keep making progress and do whatever it takes to protect coal miners from black lung disease and accidents,” she said.

A Coal Miner’s Daughter Takes on DOGE to Protect Miners’ Health

Anita Wolfe ran a mobile clinic that screened miners and tried to catch lung diseases. About a fifth of the coal miners in Central Appalachia have black lung. A 2023 NIOSH study found that coal miners are twice as likely to die of lung diseases than nonminers. In April, as part of the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency initiative, around 90% of NIOSH staff received layoff notices. Many were placed on administrative leave — including the mobile clinic crew and researchers trying to prevent these lung diseases in the first place, Wolfe says. The judge ruled in favor of the National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health and the broader National Respiratory. Division got their jobs back for now, although the program is still working to focus on individual miners and helping keep them safe from dust in the mines. But researchers elsewhere in NIOSH who also work on prevention are still slated to be laid off, that’�s a problem, she says, and it needs to change.

She remembered his wild stories about coal-loading contests and working as a mule boy. But she also remembered his death certificate, which listed black lung and silicosis, two pulmonary diseases related to dust in mines, as contributing factors.

Before she retired, Wolfe launched and ran a mobile clinic through the National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) that screened miners at their mines and tried to catch lung diseases early.

In April, as part of the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency initiative, around 90% of NIOSH staff received layoff notices. Many were placed on administrative leave — including the mobile clinic crew, workers who review miners’ test results and researchers trying to prevent these lung diseases in the first place.

Wolfe was in the courthouse to try to get those jobs back. Now, her mobile clinic workers are back, along with all the other workers in the institute’s Respiratory Health Division. But researchers elsewhere in NIOSH who also work on prevention are still slated to be laid off.

To Wolfe, that’s a problem. About a fifth of the coal miners in Central Appalachia have black lung, Wolfe said. And from 1970 to 2016, more than 75,000 died. Nationally, a 2023 NIOSH study found that coal miners are twice as likely to die of lung diseases than nonminers. Wolfe called black lung and silicosis “entirely preventable.”

“It comes down to how much is a life worth,” Wolfe said. “You want more coal, but you don’t care about the coal miners and what’s happening to them.”

* * *

For some coal miners, pausing the black lung programs at the National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health created an immediate problem, because without a stamp of approval from the institute, coal miners can’t access federal “Part 90” benefits that allow them to get reassigned to jobs with less dust exposure.

Black lung has no cure, but avoiding dust can stop the disease from getting worse. With the pause, X-rays and medical records now sat in folders, unexamined.

So Wolfe and others began campaigning, collaborating with public health workers and miners to try to get the NIOSH workers back. Wolfe enlisted the support of West Virginia Republican Sen. Shelley Capito, who successfully petitioned to get black lung workers off administrative leave in the short term. Still, that was just a temporary fix.

Sam Petsonk, a lawyer, and Harry Wiley, a coal miner, decided to sue the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees NIOSH. “To me, he was very courageous for doing that,” Wolfe said of Wiley.

At trial, Wolfe and Wiley were both called to testify, and on May 7, they sat with other witnesses in the courthouse hallway. For hours, the group made small talk about kids and summer vacations, scrupulously following instructions to avoid any chatter about the department’s “reduction in force.”

One by one the witnesses entered the courtroom. Wolfe was last. “Everything was going through my head,” she said. She was nervous. But then, she remembered her dad. “I just felt like he was there with me, you know? Kinda egging me on, like, ‘You got this, baby girl.’”

When Wolfe took the stand, she was calm, and described the value of NIOSH’s programs. The defense, she said, “didn’t offer much defense at all.”

After the trial, Wolfe joined Wiley and Petsonk for sandwiches. “They seemed fairly confident that it was gonna be found in favor of the miner,” she said.

A few days later, the judge ruled in Wiley’s favor. Staff at the mobile clinic and the broader National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health Respiratory Health Division got their jobs back for now, although the program is still working to get back up and running. Staff at the institute’s National Personal Protective Technology Lab were also called back; they certify a variety of respirators that help keep miners and other workers safe.

But other institute researchers working to prevent mining-related lung diseases heard nothing.

While researchers in the Respiratory Health Division focus primarily on tracking disease and helping individual miners, researchers at NIOSH’s Pittsburgh and Spokane Mining Research Divisions focus on innovation, developing new tools to prevent disease in the first place.

The judge’s preliminary injunction said the law requires that kind of research. But the injunction did not explicitly put Pittsburgh and Spokane researchers back to work.

The Department of Health and Human Services did un-fire their boss, a statutorily required associate director overseeing the Office of Mine Safety and Health Research. But it did not bring back the hundreds of researchers who report to that administrator.

“He’s new. He hasn’t even met us yet!” said Cassandra Hoebbel, a NIOSH researcher in Pittsburgh and a union steward for the Association of Federal Government Employees.

“A lot of people contacted me and were like, ‘Oh my God, you got your job restored!’” she said. “It’s like, no they’ve only restored a tiny part of it.”

Hoebbel said that mine health and safety research at the institute has been mostly on pause since January due to the Trump administration’s restrictions on funding and travel. For almost five months, researchers have been unable to visit mines to measure dust levels, test new equipment or improve software tools.

That’s a long-term loss for miner health, but it’s a short-term loss as well: NIOSH field work often leads to quick-fix changes by the mine operators the researchers collaborate with. Now, those improvements aren’t happening. External grants for technology development and commercialization were also “terminated for convenience.”

That’s despite the fact that, after a long decline, lung diseases in miners are again on the rise: Black lung cases have been increasing for two decades, according to a 2018 NIOSH study, and severe cases have caught back up to their all-time high. And it’s not just black lung. A 2023 study found that coal miners are dying of a variety of lung diseases at higher rates than in the past. Some are also dying younger.

* * *

“It used to be that people said black lung was an old man’s disease, and that’s not true. We just buried a thirtysomething miner,” Wolfe said.

Many younger miners suffer from lung diseases caused not by coal dust but from quartz dust, officially called respirable crystalline silica. As coal deposits became tapped out, mines went after harder-to-reach coal, generating more quartz dust from the surrounding rock. Modern mining machines may also contribute to the dust.

Silica dust exposure is not unique to coal miners, who represent a small sliver of miners in the U.S. Silicosis is common in miners at all sorts of mines.

While coal workers are eligible for “Part 90” transfers and benefits based on dust exposure, those who mine for sand, rocks, precious metals and other material are not.

For all miners, silica dust protections are decades out of date. After Wolfe’s mobile clinics helped identify new clusters of lung disease, a 2014 rule lowered allowable limits for coal dust exposure. Similar standards lowered limits for silica dust in industries like construction.

But a rule to lower by half the silica dust exposure limit in mines stalled for a decade. The rule finally passed in 2024 — then a 2025 start date was postponed, after pushback from mine operators, who said implementation would be too difficult.

Mine operators objected to a final version of the rule that said it was not enough to implement a check list of “good enough” dust control measures, to give miners masks or to rotate them in and out of dusty areas to reduce their exposure. Instead, the final rule says mines need to actually reduce the hazardous dust.

The rule also mandates silicosis monitoring programs, similar to Wolfe’s black lung monitoring work, but for non-coal miners.

However, the same day President Donald Trump held a press conference promoting the “abandoned” coal industry, the Department of Labor postponed the rule’s upcoming start date for coal mines from April to August. (Stone mines still have until April 2026 to comply.)

Earlier this year, the Department of Labor announced plans to close 34 of the mine enforcement offices that work to hold mine operators accountable for the current silica dust standard. In late May, those plans were reversed.

* * *

Dust is a constant presence in mines, and it lurks in overlooked places. Currently paused National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health research has the potential to improve the dust problem.

Decades ago, government mine safety researchers identified controls that could be used to reduce dust in mines, such as improving ventilation.

But mines have been using those strategies for years, and lung diseases stubbornly persist.

Traditionally, mine inspectors check dust levels a few times a year to confirm compliance. But those checks don’t provide much actionable information about how to make things better. That’s frustrating for mines and for miners. So NIOSH has been working on ways to make dust easier to spot.

Their personal dust monitors already let miners view their own mine dust exposure in real time. Other projects are helping miners make sense of that kind of data.

In 2015, Hoebbel observed field work for an award-winning study by institute researcher Emily Haas that outfitted miners with both a dust monitor and a video camera and then compared the feeds to see why dust levels spiked.

“They had two guys walking side by side,” Hoebbel said. One of their dust monitors “kept going up, up, up — and the other guy was walking right next to him and his was fine.”

The researchers, curious, asked, “When’s the last time you washed your sweatshirt?” Hoebbel said. “He’s like, ‘Oh man, I can’t tell you the last time I washed this thing!’”

Before the study, the participating miners felt confident that wearing masks and following established procedures would keep them safe. Afterwards, they were full of questions about silica exposure. The mine in the study, for its part, replaced cloth vehicle seats and gloves with leather, which is easier to wipe clean.

But attaching monitors to miners, while good for sussing out dirty sweatshirts, is less effective for tracking dirty equipment or faulty ventilation, which may be getting dust on sweatshirts in the first place.

So another institute project used air quality monitors to help mines and miners better understand sources of exposure within mines. In a recently published pilot study, weekly reports of real-time data helped staff at sand mine notice minute by minute shifts in dust at key locations.

As a result, the mine’s industrial hygienist turned some machines on before miners arrived for the day, so they wouldn’t be exposed to an extra burst of dust that spiked when machines were starting up.

A foreman also noticed a dust hot spot near a particular conveyor belt and used parts they had on hand to come up with a fix, reducing dust in the area threefold.

The approach is promising, and NIOSH has a history of creating useful gadgets for miners that are now widely used and often legally required. From October to January, those researchers made several site visits. Then, nothing.

That project is currently paused, along with much of NIOSH’s other research into silica exposure and impacts.

Many dust monitors test general dust levels; teasing out silica in particular means distinguishing one speck of dust from another. So researchers were working to make same-day infrared spectroscopy tests more accurate. Others were developing continuous, real-time silica monitoring tools.

Mining researchers were also collaborating with the NIOSH chemistry team to understand exposures to silica in nano-clay, or particles of clay minerals. But the institute’s analytical chemists are all still facing layoffs. So are the researchers trying to address all the other hazards miners face.

Federal mine safety and health research began in earnest in the 1910s, around the time Anita’s father was born. Back then, hundreds of coal miners died each year in mine explosions.

NIOSH and its predecessors made those incidents rare. But mine risks keep evolving: As mines age, for example, massive sinkholes can appear, and institute researchers have been helping mine operators predict them.

They are also studying ways to keep lithium batteries from exploding, working to understand if a growing number of natural gas wells could leak explosive methane into mines and devising ways to better prepare miners to survive accidents using virtual reality and to prevent accidents involving giant haul trucks.

All of that work is now on pause.

* * *

Wolfe hopes that the Department of Health and Human Services will restore NIOSH researchers voluntarily. A recent Health and Human Services draft budget for 2026 includes stable funding for mining research, even though researchers are not currently working.

In the meantime, the fate of their work could be determined by another court case, this one brought against the Trump administration by plaintiffs including Hoebbel’s union, the American Federation of Government Employees.

It’s among several lawsuits that allege that by cutting funding and staff without authorization, the administration’s DOGE initiative has usurped the powers of Congress.

Many institute layoffs were previously scheduled for June 2. But several days before, a judge issued an injunction putting the layoffs on pause until that case is adjudicated. The Trump administration has appealed that injunction to the U.S. Supreme Court.

At issue is whether Congress has the right to commit to generational goals, like the health of miners, that require stability as executives come and go.

For Wolfe, the answer is obvious. “I always tell people: ‘I’m not gonna argue with you about whether coal is good or bad. But as long as it’s mined and there are coal miners, we need to take care of them.’”

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main

Coal Miner’s Daughter Fights Back After DOGE Cuts Jobs of Health Researchers

More than 100,000 people in the U.S. suffer from black lung disease. The disease is caused by exposure to high levels of carbon monoxide in the air. The National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety is trying to prevent the disease from getting worse.

That didn’t stop DOGE from laying off about 90% of NIOSH’s staff, placing many of them on administrative leave.

Due to a lawsuit brought by a coal miner against the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees NIOSH, the mobile clinic workers and other staffers are back at work. Yet other institute researchers working to prevent mining-related lung diseases heard nothing.

Now, Anita Wolfe, who once ran a mobile clinic for NIOSH and whose father started worked as a coal miner when he was around 12 and died of causes related to black lung and silicosis, two pulmonary diseases related to dust in mines, is leading the fight to recover those jobs and protect miners’ health.

“It comes down to how much is a life worth,” Wolfe told Capital & Main’s Meg Duff. “You want more coal, but you don’t care about the coal miners and what’s happening to them.”

As Trump eyes coal revival, his job cuts hobble black lung protections for miners

NIOSH and MSHA programs suspended amid Trump administration cuts. Miners face increased risk as safety regulations enforcement weakens. Around 43,000 people are employed by the nation’s coal mines. Around 20% of coal miners in Central Appalachia now suffer from some form of black lung disease, the highest rate that has been detected in 25 years, according to the NIOSH.”You can come out from underground, make what you made, and then they can’t just get rid of you,” miner Josh Cochran says of the black lung protection programs that have been shut down by the government’s layoffs and funding cuts. “For too long, coal has been a dirty word that most are afraid to speak about,” said Jeff Crowe, who Trump identified as a West Virginia miner in a White House ceremony earlier this month. “They are great people, with great families, and come from areas of the country that we love and we really respect,” said Crowe of the coal industry’s historically supportive president.

Item 1 of 5 Josh Cochran, 45, an underground coal miner with more than 20 years of experience, holds his portable oxygen concentrator while sitting outside a law office in Oak Hill, West Virginia, U.S., April 10, 2025. REUTERS/Adrees Latif

Summary Layoffs halt black lung protection programs for miners

NIOSH and MSHA programs suspended amid Trump administration cuts

Miners face increased risk as safety regulations enforcement weakens

OAK HILL, West Virginia, April 21 (Reuters) – Josh Cochran worked deep in the coal mines of West Virginia since he was 22 years old, pulling a six-figure salary that allowed him to buy a home with his wife Stephanie and hunt and fish in his spare time.

That ended two years ago when, at the age of 43, he was diagnosed with advanced black lung disease. He’s now waiting for a lung transplant, breathes with the help of an oxygen tank, and needs help from his wife to do basic tasks around the house.

Sign up here.

His saving grace, he says, is that he can still earn a living. A federal program run by the Mine Safety and Health Administration and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health called Part 90 meant he was relocated from underground when he got his diagnosis to a desk job dispatching coal trucks to the same company, retaining his pay.

“Part 90 – that’s only the thing you got,” he told Reuters while signing a stack of documents needed for the transplant, a simple task that left him winded. “You can come out from underground, make what you made, and then they can’t just get rid of you.”

That program, which relocates coal miners diagnosed with black lung to safer jobs at the same pay – along with a handful of others intended to protect the nation’s coal miners from the resurgence of black lung – is grinding to a halt due to mass layoffs and office closures imposed by President Donald Trump and billionaire Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, according to Reuters reporting.

Reuters interviews with more than a dozen people involved in medical programs serving the coal industry, and a review of internal documents from NIOSH, show that at least three such federal programs have stopped their work in recent weeks.

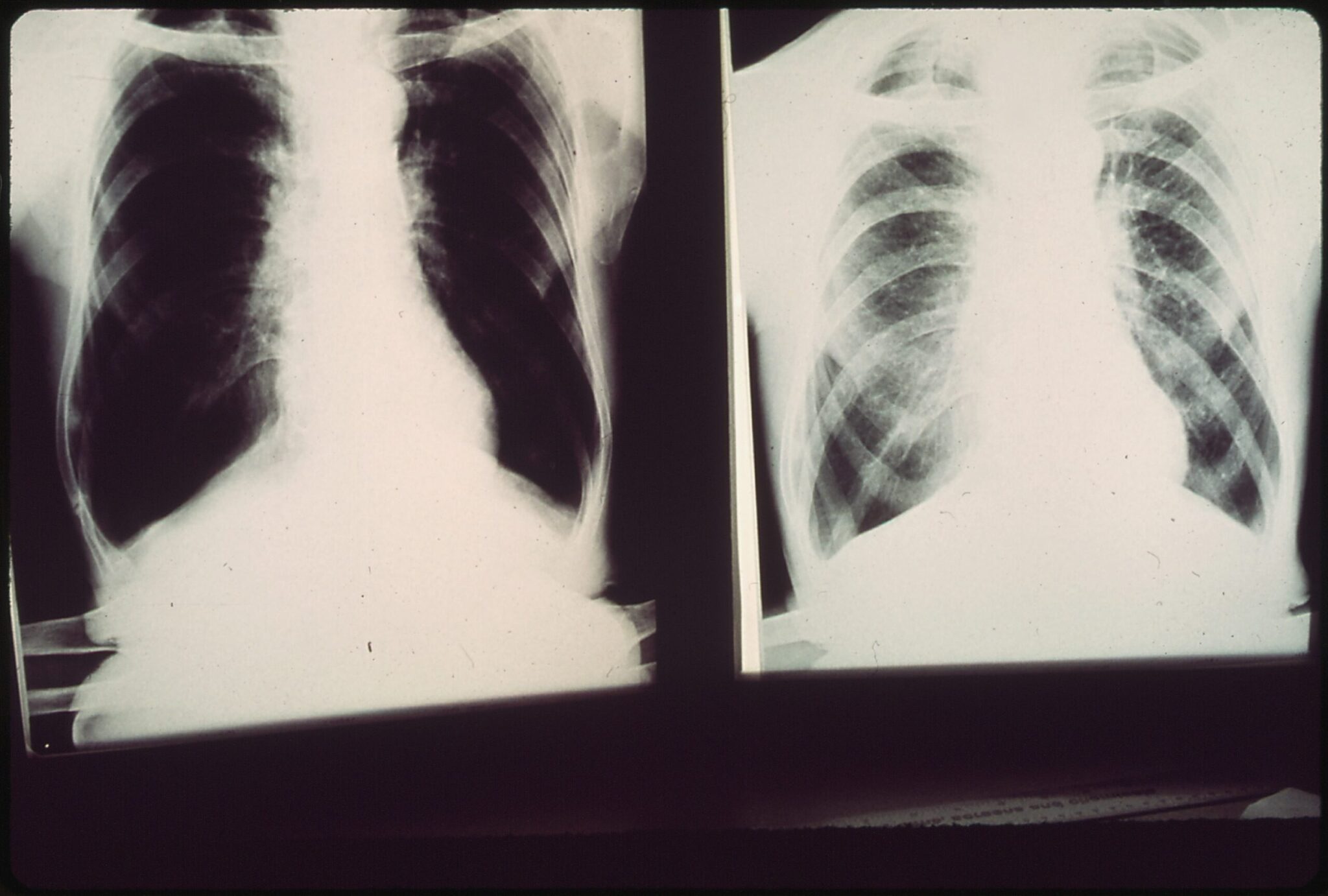

A decades-old program operated by NIOSH to detect lung disease in coal miners, for example, has been suspended. Related programs to provide x-rays and lung tests at mine sites have also shut down and it is now unclear who will enforce safety regulations like new limits on silica dust exposure after nearly half of the offices of MSHA are under review to have their leases terminated.

The details about the black lung programs halted by the government’s mass layoffs and funding cuts have not previously been reported.

“It’s going to be devastating to miners,” said Anita Wolfe, a 40-year NIOSH veteran who remains in touch with the agency. “Nobody is going to be monitoring the mines.”

The cuts come as Trump voices support for the domestic coal industry, a group that historically has supported the president.

At a White House ceremony flanked by coal workers in hard hats earlier this month, Trump signed executive orders meant to boost the industry, including by prolonging the life of aging coal-fired power plants.

“For too long, coal has been a dirty word that most are afraid to speak about,” said Jeff Crowe, who Trump identified as a West Virginia miner. Crowe is the superintendent of American Consolidated Natural Resources, successor to Murray Energy.

“We’re going to put the miners back to work,” Trump said during the ceremony. “They are great people, with great families, and come from areas of the country that we love and we really respect.”

Andrew Nixon, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees NIOSH, said that streamlining government will better position HHS to carry out its Congressionally mandated work protecting Americans.

Courtney Parella, a spokesperson for the Department of Labor said MSHA inspectors “continue to carry out their core mission to protect the health and safety of America’s miners.”

Black lung has been on the rise over the last two decades, and has increasingly been reported by young workers in their 30s and 40s despite declining coal production.

NIOSH estimates that 20% of coal miners in Central Appalachia now suffer from some form of black lung disease, the highest rate that has been detected in 25 years, as workers in the aging mines blast through rock to reach diminishing coal seams. Around 43,000 people are employed by the coal industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

MORE MINING, MORE RISK

Around 875 of NIOSH’s roughly 1,000-strong workforce across the country were terminated amid sweeping job cuts announced by HHS this month, according to three sources who worked for NIOSH.

That’s put the department’s flagship black lung program, the Coal Workers’ Health Surveillance Program, on hold, according to an internal NIOSH email dated April 4.

“We will continue to process everything we currently have for as long as we can. We have no further information about the future of CWHSP at this time,” the email says.

The CWHSP’s regular black lung screenings, which deploy mobile trailers to coal mines to test coal miners on site have ended too, because there’s no money to fuel the vehicles or epidemiologists to review the on-site x-rays or lung tests, according to sources familiar with the program.

For many miners, this program is the sole provider of medical checkups, according to NIOSH veteran Wolfe.

The loss of staff at NIOSH has also crippled black lung-afflicted miners’ ability to get relocated with pay as part of the Part 90 program.

Miners can only become eligible for the Part 90 benefit by submitting lung x-rays to NIOSH that show black lung. But all NIOSH epidemiologists in West Virginia required to review the x-rays were laid off, according to Scott Laney, who lost his job as an epidemiologist.

Laney told Reuters he and his fellow laid-off team have been working in an informal “war room” in his living room to try to draw attention to the issue among Washington lawmakers.

“I want to make sure that if there are more men who are going into the mines as a result of an executive order, or whatever the mechanism, they should be protected when they do their work,” he said.

Sam Petsonk, a West Virginia attorney who represents black lung patients, said relocating sick miners is crucial because the risks of continuing to work in dust-heavy areas while ill are so severe.

“It gets to the point that days and months matter for this program,” he said.

SILICA THREAT

Last year, MSHA finalized a new regulation that would cut by half the permissible exposure limit to crystalline silica for miners and other workers – an attempt to combat the rising rates of black lung , opens new tab

Enforcing that rule, which comes into force in August after being pushed back from April by the Trump administration, may prove difficult given the staff cuts and planned office closures at MSHA, said Chris Williamson, a former Assistant Secretary of Labor for Mine Safety and Health under the Biden administration.

He told Reuters that before he left MSHA in January, there were 20 mine inspector positions unfilled. A pipeline of 90 people that had already secured MSHA inspector job offers, meanwhile, had their offers rescinded after Trump took office, and around 120 other people took buyouts.

Mine inspectors are meant to uphold safety standards that reduce injuries, deaths and illnesses at the mines.

That loss of staff and resources raises the likelihood that black lung could become even more pervasive among Appalachian coal miners – particularly if mining activity increases, said Drew Harris, a black lung specialist in southern Virginia.

“As someone who sees hundreds of miners with this devastating disease it’s hard for me to swallow cutting back on the resources meant to prevent it,” he said.

Kevin Weikle, a 35-year-old miner in West Virginia who was diagnosed with advanced black lung disease during a screening in 2023, said the cuts make no sense at a time the administration wants to see coal output rise and will set back safety standards by decades.

“Don’t get me wrong, I mean, I’m Republican,” Weikle said. “But I think there are smarter ways to produce more coal and not gut safety.”

Reporting by Valerie Volcovici; Editing by Richard Valdmanis and Anna Driver

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Share X

Link Purchase Licensing Rights