Unreal Amber Fossils Show ‘Last of Us’ Zombie Fungus Terrorizing Bugs During the Cretaceous

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Unreal Amber Fossils Show ‘Last of Us’ Zombie Fungus Terrorizing Bugs During the Cretaceous

Fossilized fly and ant pupa are among the oldest fossil records of animal-pathogenic fungi, dating back to the Cretaceous period. The insects were infected with two species of fungi previously unknown to science. Researchers determined that both of the newly discovered fungal species belong to the genus Ophiocordyceps, which also includes a species commonly known as zombie-ant fungus. The discovery offers a rare glimpse into the rise of these highly adaptable fungal pathogens, the researchers say.. Booming diversity and abundance of insect host. species likely drove the rapid emergence of new OphiOCordyCEps species during. the early Cretassic period, researchers conclude. The fossilized fly was preserved in this state, with the fruiting body of P. ironomyiae bursting from its head. Instead of emerging from the pupa’s head, the fungus erupted out of the metapleural gland, which produces antimicrobial secretions.

An international team of researchers led by Yuhui Zhuang, a doctoral student of paleontology at China’s Yunnan University, recently found two cordyceps-infected insects trapped inside 99-million-year-old amber. The fossilized fly and ant pupa are among the oldest fossil records of animal-pathogenic fungi, dating back to the Cretaceous period. What’s more, these insects were infected with two species of fungi previously unknown to science, now named Paleoophiocordyceps gerontoformicae and Paleoophiocordyceps ironomyiae. The researchers published their findings in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B on June 11.

“Overall, these two fossils are very rare, at least among the tens of thousands of amber specimens we’ve seen, and only a few have preserved the symbiotic relationship between fungi and insects,” Zhuang told CNN.

The amber came from northern Myanmar, which has suffered violent conflict since 2017 due to a boom in fossil amber research. The study notes that the specimens the authors used were procured before 2017 and were not, to their knowledge, involved in any conflict.

Zhuang and his colleagues used optical microscopes to examine the fossilized insects, then constructed 3D images of them using an X-ray imaging technique called micro-computed tomography. This revealed surprising aspects of the insects’ infections.

The researchers determined that both of the newly discovered fungal species belong to the genus Ophiocordyceps, which also includes a species commonly known as zombie-ant fungus. The name comes from its ability to control its host’s behavior. In the final stage of the infection, the fungus seizes control of the insect’s brain and makes it seek a higher location with more sunlight and warmth—optimal conditions for spore production. Once the insect dies, a fungal growth erupts from its head and begins releasing spores that will infect new victims.

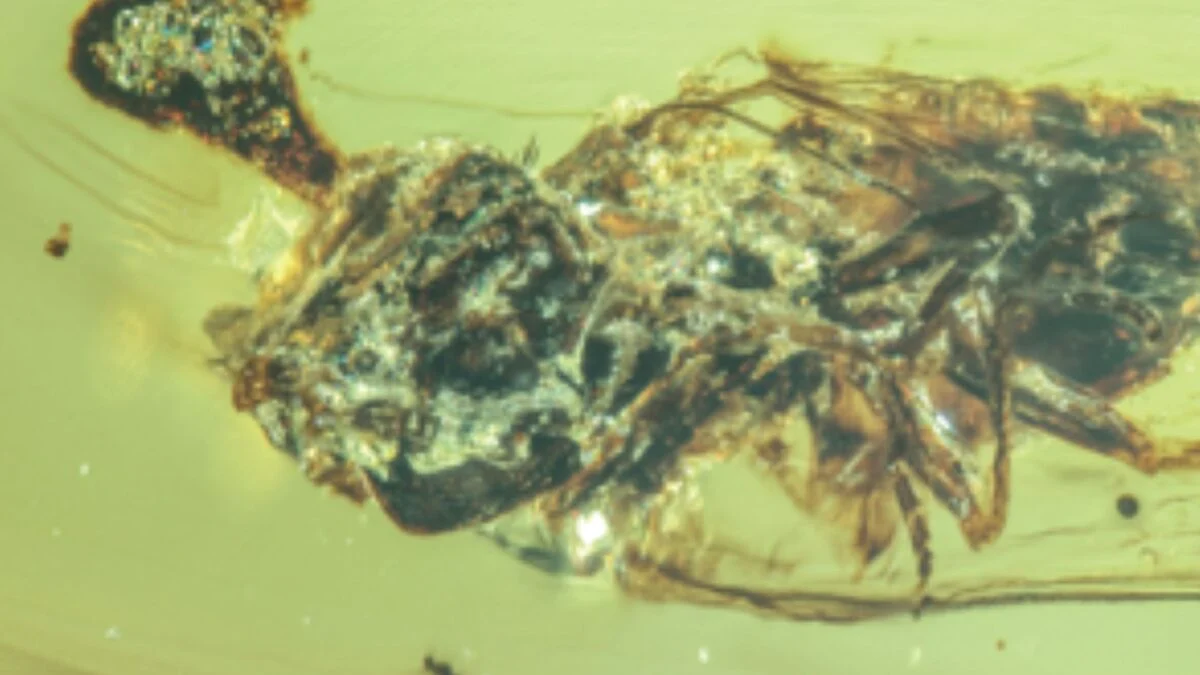

The fossilized fly was preserved in this state, with the fruiting body of P. ironomyiae bursting from its head. Unlike a typical late-stage Ophiocordyceps infection, which usually produces a fruiting body with a smooth, swollen tip, P. ironomyiae’s fruiting body was unexpanded and textured. The ant pupa, infected with P. gerontoformicae, was even more unusual. Instead of emerging from the pupa’s head, the fungus erupted out of the metapleural gland, which produces antimicrobial secretions. This has never been observed among any known species of Ophiocordyceps, the researchers note. These differences signaled that they were likely looking at two never-before-seen species.

When they compared the structures and growth patterns of these fungi to known Ophiocordyceps species, the researchers found clear traits linking them to this genus but could not match them with any documented species. They used DNA from modern Ophiocordyceps species to build phylogeny—a visual representation of the genus’ evolutionary history—then estimated where the newly discovered species diverged from their relatives.

The analysis led to a deeper understanding of Ophiocordyceps’ history, suggesting that it originated during the early Cretaceous period and started out infecting beetles. It then evolved to infect butterflies, moths, and other insects—including bees and ants—by the end of the mid-Cretaceous. Booming diversity and abundance of insect host species likely drove the rapid emergence of new Ophiocordyceps species during the Cretaceous, the researchers conclude.

Piecing together the evolutionary history of parasitic fungi has proved difficult due to a lack of ancient specimens, according to London’s Natural History Museum, one of the institutions that contributed to the research. “It’s fascinating to see some of the strangeness of the natural world that we see today was also present at the height of the age of the dinosaurs,” said co-author Edmund Jarzembowski, an associate scientist at the museum, in a statement. The discovery offers a rare glimpse into the rise of these highly adaptable fungal pathogens.