Creating a better system to assess presidential physical and psychological health

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Creating a better system to assess presidential physical and psychological health

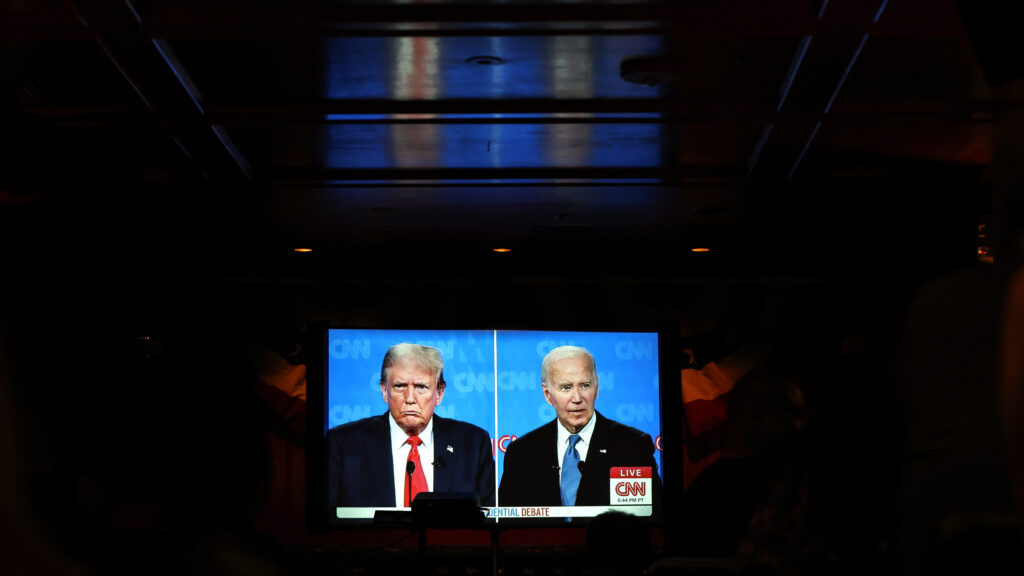

Biden’s performance left many voters concerned that he was no longer up for the job. The 25th Amendment has been shown to be problematic when it comes to cognitive decline or mental incapacity. There is no constitutional mechanism to provide an accurate report of a sitting president’s health, nor can we rely on partisan actors for valid reports because of conflicts of interest, commitment, and self-deception. The first time Cabinet officials considered using the amendment to challenge capacity was during President Reagan”s second term. But unlike Biden, Reagan was always able to perform in public, so none of these concerns were on full public display, but researchers later discovered Reagan was indeed showing subtle signs of cognitive decline. The U.S. Constitution has very little to say about a president’S health and capacity other than to declare the minimum age a president can serve (age 35); set term limits via the 22nd Amendment; and provide a process for removal by the vice president and Cabinet due to incapacity via the25th Amendment.

I’m a clinical ethicist who directs a clinical ethics consultation service; I am also a subject matter expert on decision-making capacity, consent, and surrogate decision-making. So in response to the public’s concerns about Biden’s capacity last year, I provided a clinical ethics opinion about an institution’s moral obligations regarding an impaired professional’s fitness to reliably perform his duties. I recommended three options available then to Biden: 1) He could preserve his medical privacy and autonomy by stepping down as a personal health decision; 2) if he wished to remain in office, he could release a transparent health report clearing him for fitness to serve; or 3) his staff and Cabinet, acting in the public’s interest, could insist on an independent health assessment without his consent.

advertisement

Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson’s recently released book, “Original Sin,” provides much more information and context about Biden’s decision to run for re-election. Ultimately, even after he stepped down, the Democratic Party lost the trust of many voters, and then-Vice President Kamala Harris lost the election.

There are important clinical ethics implications to this story because there is no constitutional mechanism to provide an accurate report of a sitting president’s health, nor can we rely on partisan actors for valid reports because of conflicts of interest, commitment, and self-deception.

As I wrote last July, concealment of a president’s poor health has a long tradition. But the U.S. Constitution has very little to say about a president’s health and capacity other than to declare the minimum age a president can serve (age 35); set term limits via the 22nd Amendment; and provide a process for removal by the vice president and Cabinet due to incapacity via the 25th Amendment.

advertisement

In recent years, the 25th Amendment has been shown to be problematic when it comes to cognitive decline or mental incapacity. The 25th Amendment does not define “inability” per se, so it is wide open for interpretation; the needed consensus about ability or capacity is difficult to achieve, and even so, a president could appeal such a decision.

Based on the public record, the first time Cabinet officials considered using this amendment to challenge capacity was during President Reagan’s second term. A 1987 White House memo formally raised concerns about his cognitive health and decision-making capacity. White House staff seriously considered the issue, observed him for a day, and decided he appeared competent.

Today, any formal capacity assessment would use the U-ARE criteria as part of the assessment. Although Reagan was ultimately diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 1994, his son later asserted that he had dementia in office and the family concealed it. Unlike Biden, Reagan was always able to perform in public, so none of these concerns were on full public display, but researchers later discovered Reagan was indeed showing subtle signs of cognitive decline.

There were only two other times since Reagan when the 25th Amendment was publicly discussed to remove a sitting president due to capacity concerns: in early January 2021 with Trump and in 2024 with Biden. Loyalty and conflicts of commitment reveal the 25th Amendment functionally problematic in real time unless a president dies in office or is unconscious (for instance, under general anesthesia). In 2021, in the aftermath of Jan. 6, House Republicans held a conference call debating the use of the amendment and noted that involuntary removal was an arduous process that would take too long to be useful to them, given that Biden’s inauguration was rapidly approaching. Furthermore, when it comes to questions of capacity, a president’s concerning health manifestations or behaviors can often be excused, defended, or ignored, making it challenging in a hyper-partisan environment.

advertisement

There are still no clear ethical guidelines about transparency regarding a president’s health. I have written before about the duty to warn, but White House physicians are bound only by broader clinical ethics guidelines and the HIPAA Privacy Rule, which serve as a permission structure to conceal potential health problems, and practice medicine using a “don’t ask, don’t tell” framework.

The selection of who serves as a White House physician is also at the discretion of the president and his staff. As Tapper and Thompson reveal, in the case of Biden, at no time did his physician, Kevin O’Connor (also a Biden family friend), perform any cognitive test. Recent news about President Biden’s diagnosis of prostate cancer reveals that his last PSA test was in 2014, when he was a sitting vice president, raising questions about why such a test was not done during his presidency given the gravity of what it would have revealed. While Biden was too old to automatically receive the screening under controversial guidelines, those rules are intended for the average male, not a sitting president of the United States. Tapper and Thompson’s reporting makes it clear that Biden did not have full decision-making capacity to request or refuse specific medical tests, and that his presidential aides were, in fact, making medical decisions on his behalf. Even this disturbing truth has unclear guidance per HIPAA, because if any patient defers medical decisions to anyone of his choosing, he can.

Tapper and Thompson suggested legislation could require a White House physician to submit an unvarnished health report or risk perjury, but such a law would be insufficient.

First, any physician would have wide medical judgment regarding the standard of care and interpretation of medical tests, especially if the physician were a sycophant. Second, as then-special counsel Robert Hur discovered after calling Biden “a sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory,” an unvarnished report about capacity could lead to partisan accusations of inaccuracy. Third, perjury charges are difficult to prosecute when the Justice Department is not independent, and a president can preemptively pardon anyone of perjury.

advertisement

What could go a long way to prevent similar issues would be to finally legislate an age limit of 70 at the time of inauguration for presidential candidates; this could certainly help mitigate presidential infirmity due to advanced aging, or accelerated aging while in office.

Whether or not that happens, the president should also be subject to a more independent process. One solution to a transparent health report of a sitting president is for an independent, non-political, peer-selected, medical organization, such as the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), to undertake examining presidential nominees and those in the lines of succession: vice president, speaker of the House, and president pro tempore, who is third in line to the president. (It’s currently Sen. Chuck Grassley, who is 91 years old.) This process would take place during the primary season, with annual exams thereafter for officeholders.

In this model, the health examiners would submit their independent findings for full public access. This proposed NAM-created system might be called the Comprehensive Health Examination Committee (CHEC). It would be made up of seven physician members, selected by and from the American membership of the NAM consisting of representatives from psychiatry, neurology, cardiology, oncology, and three other medical specialties. The CHEC would be a standing committee of the NAM whose members serve three-year non-consecutive terms and are independent of any outside governmental or political control. The nonpartisan CHEC would perform comprehensive health evaluations that assess physical and mental health competencies, decision-making capacity, and publish their full assessments for public view.

Members of CHEC would be accountable only to their professional peers. It would not be mandated by law but rather be a new norm that voters should demand. That way, Congress or a president would have no oversight or jurisdiction to remove CHEC members. Nominees could certainly refuse an exam. But failure to provide a published health report by the CHEC would be viewed as a significant political handicap. Those undergoing a CHEC would necessarily waive any specific privacy rights provided by HIPAA. The cost of the CHEC, as well as any associated imaging and laboratory studies, would be subsidized by the candidate’s campaign or their political action committee.

advertisement

The survival of the American experiment depends on independent scrutiny of a president’s health and capacity. Neither political party is capable of objectively determining the capacity of a commander-in-chief, nor are they able to act on objective concerns due to political fears of shunning and retribution.

M. Sara Rosenthal, Ph.D., is a professor and founding director of the University of Kentucky Program for Bioethics, Departments of Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, and Behavioral Science, and founding director of the Markey Cancer Center Oncology Ethics Program. She is chair of the UK Healthcare Ethics Committee and directs its clinical ethics consultation service.