Baseball, and the Vanishing Art of Forgiveness

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Baseball, and the Vanishing Art of Forgiveness

Dick Allen and Dave Parker will be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on Sunday. The two players were posthumously inducted, just 10 weeks after Pete Rose and Shoeless Joe Jackson were removed from the “permanently ineligible list” The cases of Rose and Jackson are well-known even to nonfans at this point. The lesser-known cases of Allen and Parker suggest a different moral calculation: How do we treat and assess players who sabotaged their own massive talent, sowing division within their clubhouses and wreckage among their teammates? It’s an intriguing subplot to this weekend’s annual Hall of Hall induction ceremony in Cooperstown, New York, says CNN’s John D. Sutter. The induction ceremony will take place at the National Museum of American History in New York City on Sunday at 3:30 p.m. ( ET) and 4:30 a.m (GMT-4:30) Sutter: Can something so gloriously frivolous as baseball teach us a thing or two about the lost art of forgiveness?

Two of the most controversial and polarizing players of their generation, Dick Allen and Dave Parker, will be enshrined there Sunday (both posthumously, alas), just 10 weeks after Major League Baseball (MLB) removed from its “permanently ineligible list” the two most famous players on the outside of the Hall looking in: Pete Rose and Shoeless Joe Jackson.

Advertisement

Advertisement Advertisement

The cases of Rose and Jackson—both banned for life after violating the MLB’s ultimate taboo against gambling on baseball—are well-known even to nonfans at this point, having been subject to numerous books, documentaries, and feature films. The lesser-known cases of Allen and Parker suggest a different moral calculation: How do we treat and assess players who sabotaged their own massive talent, sowing division within their clubhouses and wreckage among their teammates?

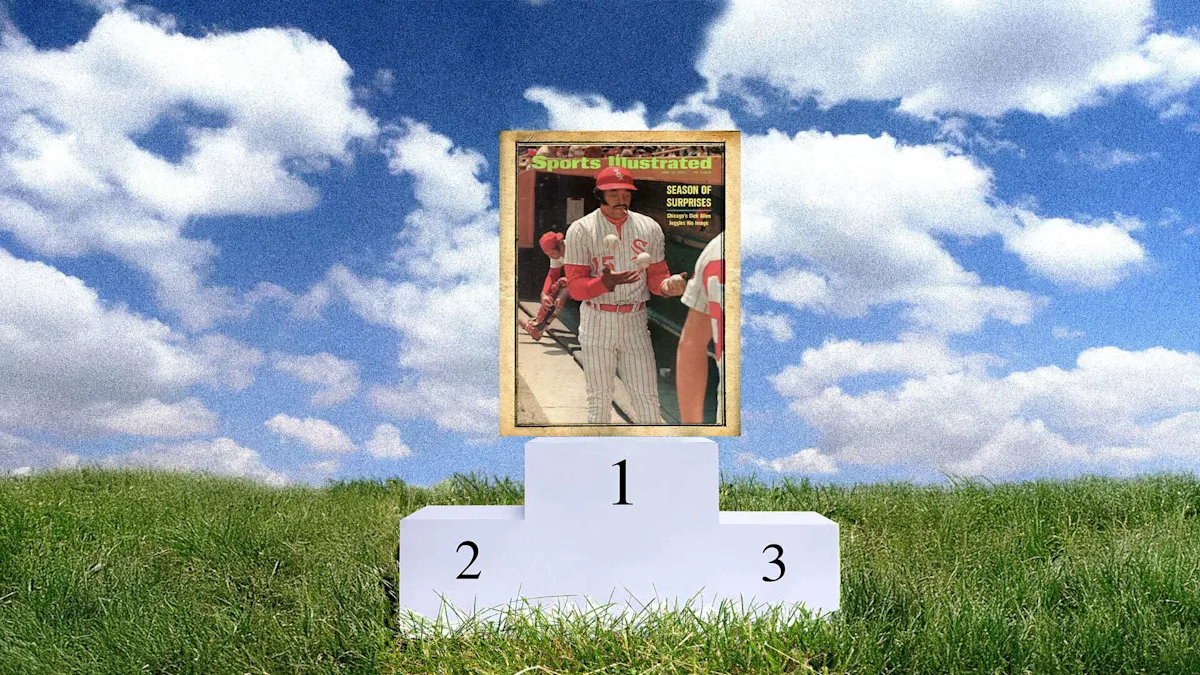

Dick Allen in 1964 had the best rookie season of any player in the 20th century, propelling the previously lackluster Philadelphia Phillies to within a game of the National League pennant. From then until 1974, there was no better hitter in baseball, not even such Hall-bound sluggers as Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson, and Willie McCovey. An intimidating presence who swung the game’s heaviest bat, Allen won a Most Valuable Player award, made seven All-Star teams, and led his league at various points in runs, homers, RBIs, walks, triples, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and more.

That’s the nice way of talking about Dick Allen. Less-flattering details would include: regularly skipping practices, showing up late to games, refusing to play when managers asked, boozing and smoking at work, hanging out at the racetrack, and on three separate occasions skipping out on his team in mid-season for weeks at a time. He was a part-time player by age 33, out of baseball by 35, and never once received as much as 20 percent of the Hall of Fame vote (you need 75 percent to get in) by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. (His election this past December was by the ex-player-voting Veterans Committee.)

As the baseball analyst/historian Bill James wrote in a notorious passage of a 1994 book, “He did more to keep his teams from winning than anybody who ever played major league baseball. And if that’s a Hall of Famer, I’m a lug nut.” Hyperbole, yes; but that was also the majoritarian view of Allen’s career for three decades after his retirement.

Advertisement

Advertisement Advertisement

So what changed? Time, and forgiveness.

As James wrote in a prescient 2009 essay (which accurately predicted that “sometime between 2020 and 2030, Dick Allen will be elected to the Hall of Fame”), “History is forgiving. Statistics endure.”

“Dick Allen did not have imaginary sins or imaginary failings as a player,” James noted. “He had very real offenses. But as time passes, the details of these incidents (and eventually the incidents themselves) are forgotten, and it becomes easier for Allen’s advocates to re-interpret them as situations in which Allen was the victim, rather than the aggressor or offender. The people who were there die off….For very good reasons, we do not nurture hatred. We let things pass. This leads history to be forgiving. Perhaps it is right, perhaps it is wrong, but that is the way it is.”

Speeding the reconciliation was the fact that a chastened, post-retirement Allen, however improbably, became a beloved figure among the same Philadelphia fans who used to hurl so many objects at his head that he wore a batting helmet while playing the field. Redemption arcs help.

Advertisement

Advertisement Advertisement

Dave Parker’s failings not only showed up more noticeably on the field than Allen’s, but they also likely injured others as well.

From 1975 to 1979, Parker was as electrifying a young player as you’re ever going to see; a mix of imposing size (6’5″, 220 pounds), startling speed (he averaged 17 stolen bases and 9 triples over those five years), and a laser cannon for a right arm. He won two batting titles, three Gold Gloves, a Most Valuable Player award (finishing in the top 20 MVP voting the other four seasons), and then crowned that five-year run with a stirring come-from-behind World Series victory in 1979 for the raucous, “We Are Family” Pittsburgh Pirates.

Parker had the coolest nickname (“Cobra”), wore the floppiest hats…and developed one of the most consequential cocaine habits in Major League history. He was front and center of the headline-generating Pittsburgh drug trials of 1985, at which 15 or so current and former players, including a half-dozen Pirates, were summoned by a grand jury to testify in what would eventually be convictions of seven Pennsylvania-based drug dealers; six from Pittsburgh, one from Philadelphia.

Granted immunity from prosecution, Parker testified that he used cocaine from 1976-1982, arranged for his main dealer to sell in the Pirates clubhouse and travel on the team plane, and facilitated transactions with at least a half-dozen players on other teams, including star L.A. Dodgers relief pitcher Steve Howe, who would go on to be the most hopeless drug addict in MLB history before dying at age 48 in a solo car crash with methamphetamine in his system. Among the Pirates teammates Parker used with, Rod Scurry died at age 36 of a cocaine-related heart attack.

Advertisement

Advertisement Advertisement

The drug trials, which led to 11 MLB suspensions (including Parker’s) that were lifted in exchange for community service and hefty salary diversions toward drug treatment programs, constituted the largest baseball scandal since the infamous 1919 Chicago Black Sox (of Shoeless Joe fame) tanked the World Series after taking payoffs from gamblers.

Parker admitted at trial what we all saw with our eyes—the cocaine, along with the booze, smokes, and lack of conditioning, made him a shell of his former on-field self. After having been one of the best four players in baseball from 1975-79, the Cobra between the usually productive ages of 29 and 32 was, shockingly, below average. The Pirates, who had been a model franchise for two decades, fell into disarray, and eventually sued Parker for breach of contract.

So…what do you do with such information? In the Hall’s case, you eventually forgive and maybe even forget, or at least compartmentalize Parker’s drug detour as the prelude for a much more respectable third act, in which the big man transitioned into an elder statesman who could still drive in 100 runs a year, earn MVP votes, and win a second championship. Here, too, redemption helped.

But not only. The human drama of athletic competition draws eyeballs to excellence, with bonus points for flair. At their peaks, Allen and Parker were not only in the conversation for best player in the game, they each had a claim on being the sport’s biggest badass. Clips from their physics-defying All-Star game exploits go viral each July—Allen in 1967 golfing a low and outside pitch well over the center field fence, Parker in 1979 rifling not one but two baserunners out from right field.

Advertisement

Advertisement Advertisement

Despite baseball’s periodic spasms of pious moralizing, the truth about fandom of all kinds is that we love our flawed characters. The late, great Ozzy Osbourne unable to successfully pour orange juice; Robert Downey, Jr., rebounding from a Steve Howe-like start to become the highest-paid actor in history; Michael Jordan being so fanatical in his competitiveness that he would bet team employees on who could throw a quarter closest to the wall. We are all fallen beings; there’s some comfort in knowing that our idols can periodically transcend deep flaws.

Such warts-and-all appreciation is foundational to some of the brighter corners of 21st-century cultural criticism: the fight breakdowns at Jomboy Media, the music writing of Steven Hyden, the long-form podcasting of Cocaine & Rhinestones. Listen to the music of The Baseball Project, or peruse the inductees at the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals, for a reminder that while character counts, sometimes characters count, too.

So are we rewarding these scofflaws for their crimes against decorum? Not quite. Allen would have made the Hall long ago had his on-field citizenship resembled that of Kirby Puckett rather than Albert Belle. Parker had to wait in line behind such contemporaries as Harold Baines, Paul Molitor, and Jim Rice, whose peaks were not nearly as high. If and when Pete Rose and Joe Jackson get their plaques, it will only come after having served out their lifetime bans.

There are cases aplenty that none of these men should be rewarded with what amounts to baseball immortality. But count me firmly on the other side. There’s a reason why reconciliation is a sacrament. Too much human error, particularly of the political variety, leads in this age of disenchantment to irrevocable condemnation, to alienation even from family; ultimately to self-isolation.

Advertisement

Advertisement Advertisement

No baseball player died for our sins (thankfully, Jesus De La Cruz still walks among us). But this weekend in Cooperstown, I will happily raise a toast not just to the two fallen badasses, but to a closer famous for failing in the postseason, a starting pitcher who tipped the scales at 300 pounds, and a Japanese fitness lunatic who by all accounts delivers the best broken-English profanity this side of Stripes. Baseball allows us to love humanity in all its fullness. May we some day remember that in the less sunny corners of life.

The post Baseball, and the Vanishing Art of Forgiveness appeared first on Reason.com.

Baseball, and the Vanishing Art of Forgiveness

Two of the most controversial and polarizing players of their generation, Dick Allen and Dave Parker, will be enshrined there Sunday (both posthumously, alas) The cases of Pete Rose and Shoeless Joe Jackson are well-known even to nonfans at this point. The lesser-known cases of Allen and Parker suggest a different moral calculation: How do we treat and assess players who sabotaged their own massive talent, sowing division within their clubhouses and wreckage among their teammates? It’s an intriguing subplot to this weekend’s annual Hall of Fame induction ceremony in Cooperstown, New York. It asks: Can something so gloriously frivolous as baseball teach us a thing or two about the lost art of forgiveness? It also asks: How can we forgive players who sowed division among their team, and within their clubhouse, and among their friends and teammates? And how can we treat players who have been in and out of the game for decades, but never made it into the Hall of Famer?

Two of the most controversial and polarizing players of their generation, Dick Allen and Dave Parker, will be enshrined there Sunday (both posthumously, alas), just 10 weeks after Major League Baseball (MLB) removed from its “permanently ineligible list” the two most famous players on the outside of the Hall looking in: Pete Rose and Shoeless Joe Jackson.

The cases of Rose and Jackson—both banned for life after violating the MLB’s ultimate taboo against gambling on baseball—are well-known even to nonfans at this point, having been subject to numerous books, documentaries, and feature films. The lesser-known cases of Allen and Parker suggest a different moral calculation: How do we treat and assess players who sabotaged their own massive talent, sowing division within their clubhouses and wreckage among their teammates?

Dick Allen in 1964 had the best rookie season of any player in the 20th century, propelling the previously lackluster Philadelphia Phillies to within a game of the National League pennant. From then until 1974, there was no better hitter in baseball, not even such Hall-bound sluggers as Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson, and Willie McCovey. An intimidating presence who swung the game’s heaviest bat, Allen won a Most Valuable Player award, made seven All-Star teams, and led his league at various points in runs, homers, RBIs, walks, triples, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and more.

That’s the nice way of talking about Dick Allen. Less-flattering details would include: regularly skipping practices, showing up late to games, refusing to play when managers asked, boozing and smoking at work, hanging out at the racetrack, and on three separate occasions skipping out on his team in mid-season for weeks at a time. He was a part-time player by age 33, out of baseball by 35, and never once received as much as 20 percent of the Hall of Fame vote (you need 75 percent to get in) by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. (His election this past December was by the ex-player-voting Veterans Committee.)

As the baseball analyst/historian Bill James wrote in a notorious passage of a 1994 book, “He did more to keep his teams from winning than anybody who ever played major league baseball. And if that’s a Hall of Famer, I’m a lug nut.” Hyperbole, yes; but that was also the majoritarian view of Allen’s career for three decades after his retirement.

So what changed? Time, and forgiveness.

As James wrote in a prescient 2009 essay (which accurately predicted that “sometime between 2020 and 2030, Dick Allen will be elected to the Hall of Fame”), “History is forgiving. Statistics endure.”

“Dick Allen did not have imaginary sins or imaginary failings as a player,” James noted. “He had very real offenses. But as time passes, the details of these incidents (and eventually the incidents themselves) are forgotten, and it becomes easier for Allen’s advocates to re-interpret them as situations in which Allen was the victim, rather than the aggressor or offender. The people who were there die off….For very good reasons, we do not nurture hatred. We let things pass. This leads history to be forgiving. Perhaps it is right, perhaps it is wrong, but that is the way it is.”

Speeding the reconciliation was the fact that a chastened, post-retirement Allen, however improbably, became a beloved figure among the same Philadelphia fans who used to hurl so many objects at his head that he wore a batting helmet while playing the field. Redemption arcs help.

Dave Parker’s failings not only showed up more noticeably on the field than Allen’s, but they also likely injured others as well.

From 1975 to 1979, Parker was as electrifying a young player as you’re ever going to see; a mix of imposing size (6’5″, 220 pounds), startling speed (he averaged 17 stolen bases and 9 triples over those five years), and a laser cannon for a right arm. He won two batting titles, three Gold Gloves, a Most Valuable Player award (finishing in the top 20 MVP voting the other four seasons), and then crowned that five-year run with a stirring come-from-behind World Series victory in 1979 for the raucous, “We Are Family” Pittsburgh Pirates.

Parker had the coolest nickname (“Cobra”), wore the floppiest hats…and developed one of the most consequential cocaine habits in Major League history. He was front and center of the headline-generating Pittsburgh drug trials of 1985, at which 15 or so current and former players, including a half-dozen Pirates, were summoned by a grand jury to testify in what would eventually be convictions of seven Pennsylvania-based drug dealers; six from Pittsburgh, one from Philadelphia.

Granted immunity from prosecution, Parker testified that he used cocaine from 1976-1982, arranged for his main dealer to sell in the Pirates clubhouse and travel on the team plane, and facilitated transactions with at least a half-dozen players on other teams, including star L.A. Dodgers relief pitcher Steve Howe, who would go on to be the most hopeless drug addict in MLB history before dying at age 48 in a solo car crash with methamphetamine in his system. Among the Pirates teammates Parker used with, Rod Scurry died at age 36 of a cocaine-related heart attack.

The drug trials, which led to 11 MLB suspensions (including Parker’s) that were lifted in exchange for community service and hefty salary diversions toward drug treatment programs, constituted the largest baseball scandal since the infamous 1919 Chicago Black Sox (of Shoeless Joe fame) tanked the World Series after taking payoffs from gamblers.

Parker admitted at trial what we all saw with our eyes—the cocaine, along with the booze, smokes, and lack of conditioning, made him a shell of his former on-field self. After having been one of the best four players in baseball from 1975-79, the Cobra between the usually productive ages of 29 and 32 was, shockingly, below average. The Pirates, who had been a model franchise for two decades, fell into disarray, and eventually sued Parker for breach of contract.

So…what do you do with such information? In the Hall’s case, you eventually forgive and maybe even forget, or at least compartmentalize Parker’s drug detour as the prelude for a much more respectable third act, in which the big man transitioned into an elder statesman who could still drive in 100 runs a year, earn MVP votes, and win a second championship. Here, too, redemption helped.

But not only. The human drama of athletic competition draws eyeballs to excellence, with bonus points for flair. At their peaks, Allen and Parker were not only in the conversation for best player in the game, they each had a claim on being the sport’s biggest badass. Clips from their physics-defying All-Star game exploits go viral each July—Allen in 1967 golfing a low and outside pitch well over the center field fence, Parker in 1979 rifling not one but two baserunners out from right field.

Despite baseball’s periodic spasms of pious moralizing, the truth about fandom of all kinds is that we love our flawed characters. The late, great Ozzy Osbourne unable to successfully pour orange juice; Robert Downey, Jr., rebounding from a Steve Howe-like start to become the highest-paid actor in history; Michael Jordan being so fanatical in his competitiveness that he would bet team employees on who could throw a quarter closest to the wall. We are all fallen beings; there’s some comfort in knowing that our idols can periodically transcend deep flaws.

Such warts-and-all appreciation is foundational to some of the brighter corners of 21st-century cultural criticism: the fight breakdowns at Jomboy Media, the music writing of Steven Hyden, the long-form podcasting of Cocaine & Rhinestones. Listen to the music of The Baseball Project, or peruse the inductees at the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals, for a reminder that while character counts, sometimes characters count, too.

So are we rewarding these scofflaws for their crimes against decorum? Not quite. Allen would have made the Hall long ago had his on-field citizenship resembled that of Kirby Puckett rather than Albert Belle. Parker had to wait in line behind such contemporaries as Harold Baines, Paul Molitor, and Jim Rice, whose peaks were not nearly as high. If and when Pete Rose and Joe Jackson get their plaques, it will only come after having served out their lifetime bans.

There are cases aplenty that none of these men should be rewarded with what amounts to baseball immortality. But count me firmly on the other side. There’s a reason why reconciliation is a sacrament. Too much human error, particularly of the political variety, leads in this age of disenchantment to irrevocable condemnation, to alienation even from family; ultimately to self-isolation.

No baseball player died for our sins (thankfully, Jesus De La Cruz still walks among us). But this weekend in Cooperstown, I will happily raise a toast not just to the two fallen badasses, but to a closer famous for failing in the postseason, a starting pitcher who tipped the scales at 300 pounds, and a Japanese fitness lunatic who by all accounts delivers the best broken-English profanity this side of Stripes. Baseball allows us to love humanity in all its fullness. May we some day remember that in the less sunny corners of life.

The post Baseball, and the Vanishing Art of Forgiveness appeared first on Reason.com.

Source: https://sports.yahoo.com/article/baseball-vanishing-art-forgiveness-103047521.html