Beyond fertility and menopause: See why the ovary is central to women’s health and longevity

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Beyond fertility and menopause: See why the ovary is central to women’s health and longevity

Ovarian aging has widespread effects on women’s health, increasing the risk of age-related diseases and other conditions. An ovary contains anywhere from 100,000 to 2 million tiny fluid-filled sacs called follicles. Each follicle holds an immature egg and cells that support the egg’s development. Some experts say that delaying ovarian aging could help women avoid a cascade of health problems and live healthier longer.. The path from follicle to egg is remarkably long. While we think of the menstrual cycle as a monthly event, a woman’s period is more than a year in the making. At any moment, there is a lot happening in the ovary − some follicles are just beginning their recruitment process (about 1,000 are recruited each month), others are growing, and a few are nearing maturity. This ongoing, overlapping cycle makes ovarian function complex and dynamic. The ovary also has many other functions enabled by receptors throughout the body that affect bone and heart health, metabolism and overall well-being.

Here’s a closer look at why the ovary affects health, how you can stay healthier longer, and ways researchers are trying to better understand this often-overlooked but crucial organ.

Living longer, but not necessarily better

Women live longer than men on average, but they end up spending more time living with diseases or disabilities. Research shows that health outcomes are closely tied with menopause and declining ovarian function. Before reaching menopause, women are less likely than men of the same age to develop cardiovascular disease, but once they reach 55, their risk becomes greater than men’s.

The risk of dying from a cardiovascular event is higher for women who experience menopause earlier in life, according to a study in the Journal of the American Heart Association. Another study found that experiencing menopause later in life made it more likely someone would live to 90 and that earlier menopause increased the risk of dying younger. And a paper published in the journal Brain Communications showed women with longer reproductive windows were better protected against progressive forms of multiple sclerosis.

It’s not only deadly diseases that are linked to ovarian health; women also experience more chronic, non-life-threatening illness than men after age 45. As ovaries age, the risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline increases. Some experts say that delaying ovarian aging could help women avoid a cascade of health problems and live healthier longer.

“Why is it OK to extend our lifespan as much as we are and not try to live healthier longer? And I think for women, this discussion of health span really has to include reproductive function,” said Francesca Duncan, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University.

How do ovaries work?

At birth, an ovary contains anywhere from 100,000 to 2 million tiny fluid-filled sacs called follicles. Each follicle holds an immature egg and cells that support the egg’s development. The number of follicles varies greatly, but one thing is certain: Every woman is born with all of the follicles she will ever have. Only about 300,000 may remain by the time she reaches puberty.

The path from follicle to egg is remarkably long. While we think of the menstrual cycle as a monthly event, a woman’s period is more than a year in the making. At any moment, there is a lot happening in the ovary − some follicles are just beginning their recruitment process (about 1,000 are recruited each month), others are growing, and a few are nearing maturity. This ongoing, overlapping cycle makes ovarian function complex and dynamic.

From each cohort of about 1,000 follicles, only one typically reaches maturity and ovulates, releasing an egg for fertilization. The others are degraded by the ovary. Why certain follicles survive remains a mystery.

“It’s like a ball of balls, little tiny different-size balls, and each one of those different balls is going through this incredible remodeling at the level of cells. They change what kind of hormones they make, they change the way they look, they change what their function is across time,” said Jennifer Garrison, an associate professor based at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging and the Global Consortium of Reproductive Longevity and Equality.

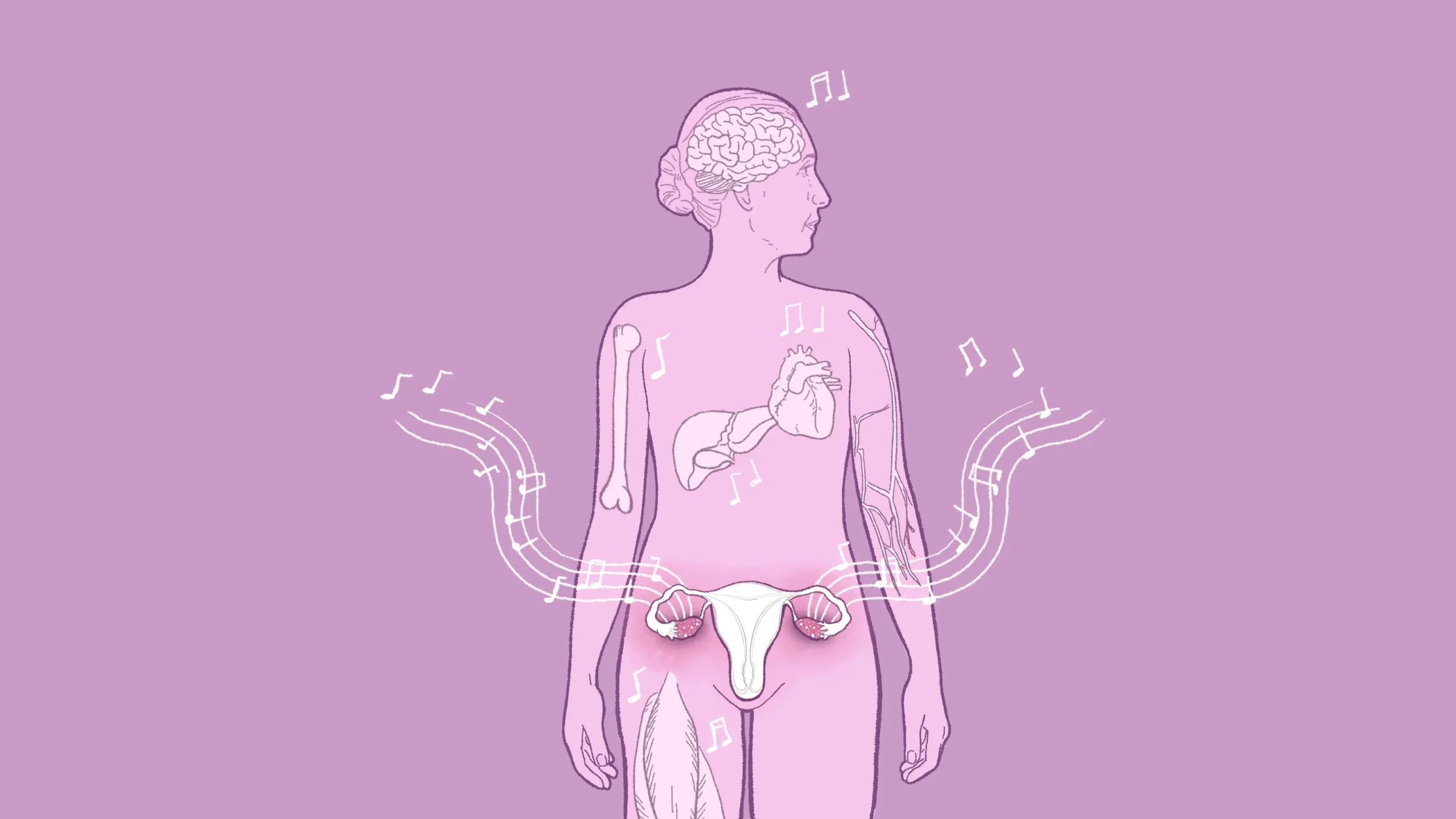

A symphony of hormones

Despite being known as reproductive organ, the ovary does much more, Garrison said. “I genuinely do think that calling them reproductive organs has really made women’s health small. Focusing it through the lens of fertility has really made it seem small, and we have to make it clear that we are talking about the health of women, period.“

Only about 400 to 500 follicles release an egg during a woman’s life. Thousands of others die off, but before they do, the supporting cells inside produce hormones. These hormones communicate with their egg and with the ovary, regulating the menstrual cycle, but also have many other functions enabled by receptors throughout the body. Traveling through the bloodstream to the brain, bones, blood vessels, breasts and other organs with receptors, hormones affect bone and heart health, metabolism and overall well-being.

Garrison studies these two-way dynamic chemical conversations and likens the process to a symphony in which hormones act as notes, creating an interplay between ovaries and organs. “Your ovaries are communicating via hormones, and not just the ones you know about but probably dozens if not hundreds of hormones talking to your bones, to your brain, to your liver, talking to your muscle, talking to almost every other organ in your body.” As ovaries decline, hormones change, and a harmonious symphony can turn into a cacophonous noise, impacting the entire body.

“We don’t understand those individual conversations. We have no idea how most of them work. But what we do know is what happens when either ovaries aren’t working properly, or when you take them away, and so we can infer what the contribution of ovaries is to say, for example, bone density,” Garrison said.

Take one of the hormones ovaries produce: estrogen. Estrogen is essential to bone health because it promotes the activity of osteoblasts, the cells that make new bone. During menopause, women lose about 10% of their bone density on average, and some could lose up to 20% in the first five years. A drop in estrogen also affects skeletal muscle mass and strength, increasing the risk of fractures from falls. After age 50, as many as 1 in 2 women (but only 1 in 5 men) break a bone. Studies show postmenopausal women, particularly those with early menopause, may be at higher risk for rheumatoid arthritis, a long-term condition that causes pain, swelling and stiffness in the joints.

Estrogen also influences many areas of the brain. Longer exposure to estradiol, the type of estrogen produced by the ovaries during a woman’s reproductive years, may help keep the brain healthier and lower the risk of certain diseases. For example, earlier menopause is associated with increased risk of dementia, according to a 2023 study.

Women are protected from heart disease during their reproductive years because estrogen helps expand blood vessels, grow new ones and lower inflammation. Better blood flow reduces strain on the heart, and wider blood vessels reduce resistance in circulation, leading to lower blood pressure. After menopause, estrogen levels drop, and the risk of heart disease increases.

Estrogen also helps regulate blood sugar by supporting insulin production, improving insulin sensitivity, and reducing fat storage and inflammation. The hormone also plays a role in maintaining brain function and metabolism, ensuring the body uses glucose for energy efficiently. The drop in estrogen associated with menopause makes it more likely that women will gain weight around the abdomen, increasing the risk of conditions like type 2 diabetes, heart disease and certain cancers.

What goes wrong with ovaries over time?

The number of follicles progressively declines with age. By age 30, most women have only about 12% of the egg cells they were born with. After a certain point they lose follicles at a faster rate, though it’s not known why. By age 40, a mere 3% may remain.

The quality of follicles also worsens with age, and they are more likely to have defects. For example, if a follicle releases an egg, the egg might have missing chromosomes or have too many, which makes it harder to get pregnant.

Countless cycles of follicular growth also leave their mark on ovaries. A thousand follicles dying so that one can make it to the final stage means there is a lot of debris for the body to clean up. Many other organs experience more gradual wear and tear with age, but the ovary has an immense degree of cellular turnover.

As a follicle reaches ovulation, it ruptures to release an egg, leaving a temporary wound behind on the surface of the ovary, which must then heal. According to Duncan, this process normally occurs hundreds of times in a woman’s life, and over time these micro-injuries degrade the ovary’s structural integrity affecting its function. All of this means the ovary becomes stiffer with age.

“It’s maybe not so stark as a sponge to a rock,” Duncan said. “But that’s the idea, that you’re going from something that’s very soft to something that’s very rigid and tough.”

As all of these issues accumulate the once tightly regulated system where hormones fluctuate in predictable cycles begins to break down. That’s when perimenopause begins, a phase that can last for a decade before menstruation stops completely. The body is no longer receiving the level of hormones it has been accustomed to since puberty. Many women start having hot flashes, have trouble sleeping and experience vaginal dryness. Some experience mood changes and brain fog. As many as 135 different symptoms are associated with perimenopause and can come at various intensities. Ultimately this phase is followed by menopause, defined as 12 full months since a woman’s last menstrual period. By that time, a woman has about 1,000 follicles remaining.

Many things can influence when a woman will reach menopause: not only her mother’s age at menopause but the timing of her first period, her body mass index, lifestyle choices, use of birth control, number of pregnancies, and other factors like education and income level. Women with cancer going through chemotherapy or radiation often have accelerated ovarian aging. Endocrine disrupting chemicals may also cause a woman to go through menopause earlier.

The end of periods doesn’t mean the ovaries stop working; they continue to make estrogen at much lower levels as well as testosterone. Rather, menopause means the end of menstruation and fertility.

“Some women will be postmenopausal and for whatever reason be advised to have their ovaries removed surgically, and they can feel the difference,” said Cynthia Stuenkel, clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Ovarian problems can affect a woman’s health at any age. For a 10-year-old girl, ovarian dysfunction could mean trouble going through puberty, irregular menstrual cycles, or even acne. Garrison says that for a woman in her 20s, it might uncover risks of autoimmune disorders or conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome. By the time a woman reaches her 30s, ovarian problems are more commonly linked to infertility and miscarriages. And after menopause, the risks shift again − heart disease, osteoporosis and cognitive decline become bigger concerns.

What can be done to manage ovarian decline?

Lifestyle changes are probably the most important tools, Stuenkel said. Regular exercise − especially strength training − helps protect bone and muscle health, and a good diet can help counteract metabolic changes. It’s also important to manage stress and get enough sleep. Though lifestyle changes can’t stop ovarian aging, they can ease the transition and lower long-term health risks. There are also many options for managing symptoms, such as nonhormonal drugs and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Hormone therapy is another option. The treatment seeks to replicate ovarian function by replenishing hormones depleted during menopause. It is most often used to treat hot flashes and vaginal discomfort. The therapy was prescribed for decades before its use dropped sharply in 2002 after a Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study linked it to slightly higher risks of breast cancer, heart attack and stroke in postmenopausal women.

In May 2024, a review highlighted that the hormones, doses and delivery methods used in the WHI trials were different from modern treatments. Unlike the oral-only therapy in the study, today’s patches use lower doses of hormones which are identical to the ones made by the body, and may reduce risks, according to the review. The timing also matters – most WHI participants started therapy a decade after menopause, which may have affected outcomes.

Starting hormone replacement closer to menopause may be much more effective, according to another study. Though hormone therapy may benefit heart health if started early in menopause, it’s generally not recommended for women who already have a high risk of heart disease, stroke or a history of coronary problems, according to a review led by the American College of Cardiology Cardiolovascular Disease in Women Committee. But research indicates long-term benefits of the therapy could outweigh the risks.

The treatment does have its limits: Estrogen and progesterone in premenopausal women are tightly regulated in cycles, but hormone replacement therapy provides a constant dosage while wearing a patch, or a spike when taking a pill. Also, estrogen receptors, which can be compared to locks on cells with estrogen being the key that activates them, may decrease with age. This means that even if estrogen is available via replacement therapy, cells may be less responsive to it.

How can women keep track of what’s going on with their ovaries?

Unlike other organs where function can be measured with routine tests, there is no simple diagnostic tool to track ovarian aging. The biggest clue is something most women are already familiar with: their period.

Regular cycles signal ovaries are producing hormones in a predictable rhythm, while irregular or skipped periods can be an early indication of decline. For many women, the first sign of approaching menopause isn’t a sudden change but a slow and erratic shift in their cycles. Menstrual irregularities can also indicate stress, hormonal imbalances, gynecological diseases and infections.

“Vital signs in medicine are things like heart rate, blood pressure, breathing and temperature,” Stuenkel said. “Those are the key. When we get a new patient in the hospital, the attendants say, ‘Tell me the vital signs.’ I really like the concept of the menstrual cycle as a vital sign because it tells you so much about women’s health.”

But women who take hormonal contraception may not experience obvious menstrual changes at all, and those who have conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome may already have irregular periods. There are also women with regular periods who want to know how fertile they are. In this case, doctors measure the level of Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), which is made by follicles. They can also check the antral follicle count (AFC), or the number of follicles, in the later part of their journey toward possible ovulation.

According to Garrison, current methods provide only a snapshot rather than a complete picture of a woman’s ovarian health trajectory.

Can women delay ovarian aging?

Garrison and Marinova say reproductive aging is greatly under-researched. A lack of suitable organisms to model and study human menopause makes it challenging to develop interventions, as does sex bias and lack of funding.

“This touches every single person with ovaries. It’s a tremendous problem, and there’s a tremendous opportunity,” Goldman said. “But there aren’t that many people focusing on it, and the funding is very limited. And so, I think that the progress will be halted if there isn’t proper funding to continue this work.”

An emerging trend known as decentralized science is exploring ways to raise money for early-stage research through community-driven efforts. For example, AthenaDAO − a self-described decentralized community of researchers, funders and advocates − is funding research on women’s health, including ovarian aging.

There are only a handful of companies focused on reproductive longevity. One of them is Oviva Therapeutics. It is in the early stages of testing whether a pharmaceutical version of anti-Müllerian hormone, which helps regulate how many follicles start developing each menstrual cycle, could help reduce egg loss.

Some scientists are exploring compounds that may show promise in other areas of aging and applying them to ovarian health. Rapamycin is an antifungal approved by the FDA as an immune suppressor that prevents organ recipients from rejecting a new organ. Rapamycin prolonged life when given to yeast, worms, flies and mice and has raised hopes of possibly slowing down the aging process in humans. One study is testing whether it can slow ovarian aging, delay menopause, extend fertility and reduce risks of age-related disease. The clinical trial plans to include more than 1,000 women and has 50 participants so far. Early results suggest rapamycin could slow ovarian aging by 20%. Participants have reported better health, memory, energy, and skin and hair quality.

Duncan, the professor at Northwestern, is focused on using ovarian stiffness as a way to track ovarian aging through noninvasive imaging and as a target for treatment. Her research shows that reducing fibrosis in the ovary with medication may help preserve hormone production, improve ovulation and possibly slow ovarian decline.

Another strategy could be ovarian cryopreservation. A small piece of ovarian tissue is frozen and later replaced, a technique used to preserve fertility in cancer patients. Mathematical models suggest the procedure could significantly delay menopause. But obtaining and freezing ovarian tissue requires surgery, which could carry risk.

More research is needed to understand the future of women’s health

Women who go through menopause after 55 have a higher risk of breast, ovarian and endometrial cancers. This is likely because they have been exposed to estrogen for a longer time. The risk may be higher for women who started their periods early, according to a study published in the National Institute of Health’s National Library of Medicine. Other risks of delaying ovarian aging may remain unknown.

“This is why we have to study it. And I think that the assumption is that the benefits of prolonged ovarian function would far outweigh the risks,” Goldman said. “We need to be able to offer treatments to women when they ask, ‘I understand that my ovaries are aging; what can I do about it?’ And my answer right now is there is not much we can do, and we are studying, and we are working, and we want to answer these questions, but we don’t have answers.”

Another concern about delaying ovarian aging is the assumption that it could mean women have periods and remain fertile in the later decades of life, even if their bodies may no longer be able to support a pregnancy.

“We’re not trying to just extend this function just so people can have a million babies, but to really make sure that the endocrine function is matching how long we are living,” Duncan said.

Ovarian aging could be an area where a personalized approach may make a big difference. For example, women could take molecules that act like estrogen but are designed to target only certain tissues − supporting bone, brain and muscle while avoiding unwanted effects on breast tissue, according to Garrison. She imagines a future when instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, women could take a combination of compounds tailored to them.

“There should be a diagnostic panel that would tell you like, here’s what’s most likely to work for you, and there should be a menu of options.”

Contributing: Ramon Padilla and Shawn J. Sullivan.

More visual health guides from USA TODAY:

Feeling hangry? From food cravings to brain fog, blood sugar spikes may be the cause

Want to live healthier longer? Visual guide shows how longevity science looks to slow diseases of aging

Girls, LGBQ+ teens at higher risk for depression, CDC mental health report says

How to boost your immune system to fight germs