From sports desk to nature’s frontlines: David Akana’s unlikely path to lead Mongabay Africa

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

From sports desk to nature’s frontlines: David Akana’s unlikely path to lead Mongabay Africa

David Akana, Director of Programs at Mongabay Africa, leads with a vision of inclusive, long-term environmental journalism. He emphasizes patience, integrity, and a mission-driven approach to storytelling in the face of disinformation and growing environmental threats. Since taking the helm, Akana has built a diverse, multilingual newsroom and expanded Mongaby’s reach across the continent. He has a strategic focus on reporting in local languages like Swahili to deepen engagement and impact. Akana: “Any journalist can become an environmental journalist if they have the commitment to do it’With biodiversity and climate issues poised to define Africa’s future, Mongabays role is vital.” He says, “Mongabay must continue to play a vital role in documenting these changes but also in helping citizens engage with them”. See All Key Ideas at Mongbay.com/Key-Ideas-Mongbay-2025-David-Akana-Leading-Environmental-Journalism.

Since taking the helm, Akana has built a diverse, multilingual newsroom and expanded Mongabay’s reach across the continent, with a strategic focus on reporting in local languages like Swahili to deepen engagement and impact.

Grounded in the belief that journalism can inform, empower, and hold power to account, Akana emphasizes patience, integrity, and a mission-driven approach to storytelling in the face of disinformation and growing environmental threats.

Akana spoke with Mongabay Founder and CEO Rhett Ayers Butler in July 2025. See All Key Ideas

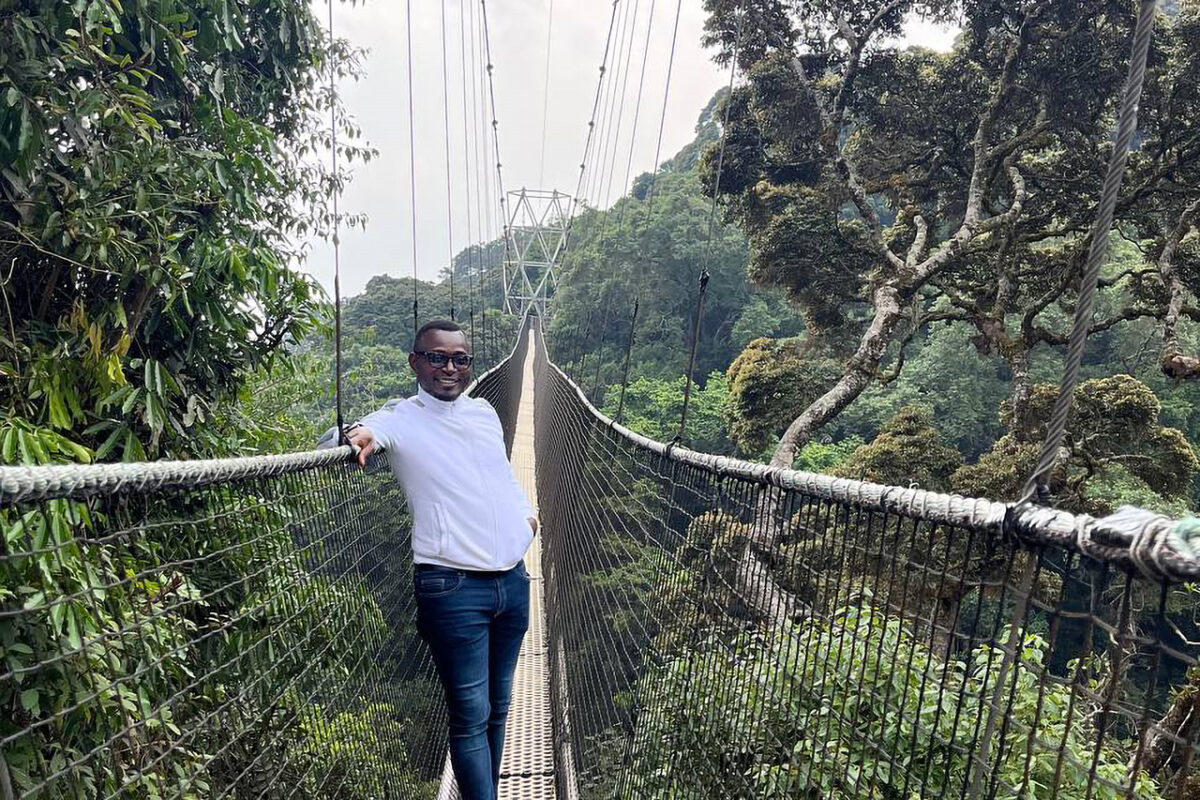

In an era where the stakes for biodiversity, climate, and sustainable development are rising across the African continent, David Akana is advancing a model of environmental journalism rooted in rigor, inclusion, and long-term impact. As Director of Programs at Mongabay Africa, Akana oversees everything from editorial strategy and partnerships to resource mobilization and newsroom operations. But his role is more than administrative; it’s deeply personal, shaped by a career that has spanned sports reporting, international development communications, and frontline environmental storytelling.

Akana’s journey into environmental journalism began over two decades ago in Cameroon. A former sports journalist with a deep love for football, he shifted tracks in 2002 when he joined the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in Central Africa. At the time, the move was driven by pragmatic considerations—financial stability and a chance to take on editorial leadership—but it marked a turning point. Grappling with topics like biodiversity loss and climate change wasn’t easy, but the complexity of the issues ultimately became part of the draw.

“Once I was out in the field,” he says, “I realized how high the stakes truly were.”

That sense of purpose has only grown. For Akana, journalism is not just about reporting facts—it’s about helping people make sense of the systems that shape their lives, particularly in regions where political and economic accountability is weak. In places where power is concentrated among a few and basic rights are often out of reach, he argues, journalism remains one of the few tools capable of amplifying marginalized voices, exposing corruption, and informing communities.

In leading Mongabay’s operations across Africa, Akana brings a deep understanding of the continent’s diversity and its underreported environmental narratives. Since taking the helm, he has worked to establish a sustainable foundation for the bureau, building a 17-person team, developing editorial programs in multiple languages, and expanding the organization’s reach from the Congo Basin to coastal West Africa and the Horn. He’s especially focused on the future: launching a Swahili-language version of Mongabay Africa and laying the groundwork for reporting in other widely spoken African languages like Hausa, Pidgin, and Amharic.

“Reporting in local languages,” he says, “is how Mongabay can succeed in Africa over the long term.”

Akana is also clear-eyed about the challenges. He notes that environmental journalism no longer delivers the instant impact it once did in the early days of television, especially in a digital landscape rife with disinformation and greenwashing. Yet, he sees Mongabay’s steady, credible coverage as a counterweight to those forces.

“Impact and influence take time,” he reflects. “But when done consistently and credibly, environmental journalism can shape policies, empower communities, and change narratives.”

That philosophy is evident in the stories Mongabay Africa is publishing—from investigations into extractive industries in the Democratic Republic of Congo to coverage of REDD+ schemes in the Republic of Congo and land-use conflicts across the continent. In several cases, Mongabay’s reporting has catalyzed corporate change, informed global investment decisions, and helped elevate community concerns to international forums.

What makes Akana’s leadership distinctive is his belief in building teams that reflect Africa’s diversity, coupled with a commitment to mentorship and mission-driven journalism. He doesn’t see himself as inherently exceptional—just someone who stayed curious, kept learning, and was willing to make mistakes. “Any journalist,” he says, “can become an environmental journalist if they have the commitment.”

With biodiversity and climate issues poised to define Africa’s future, Akana sees Mongabay playing an essential role not only in documenting these changes but also in helping citizens engage with them.

“Mongabay,” he says, “must continue to play a modest yet vital role—step by step—providing accurate information to help Africans better manage their vast resources.”

What follows is a wide-ranging conversation with David Akana on leadership, impact, environmental journalism, and his vision for the future of Mongabay Africa.

An interview with David Akana

Mongabay: Please introduce yourself and your position at Mongabay.

David Akana: My name is David Akana. I’m the Director of Programs at Mongabay Africa.

Mongabay: And what does your day-to-day work at Mongabay Africa look like?

David Akana: My daily work at Mongabay Africa involves helping shape the short-term and long-term editorial direction through contributions to developing the annual work plan. It also involves building and strengthening partnerships with other media outlets and key stakeholders to expand Mongabay’s reach and influence. I also contribute to efforts to raise resources. As the organization continues to grow, I spend a considerable amount of my time responding to a rising number of inquiries from various stakeholders. Recently, a lot of my time has also been dedicated to producing stories. Lastly, a significant part of my daily responsibilities involves HR-related tasks, ensuring smooth operations within the team.

Mongabay: And what did you do before you joined Mongabay?

David Akana: I worked in corporate communications, a journey that took me from the World Bank in Washington, D.C., to the African Development Bank and CORAF. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, I joined the African Union Commission, where I supported communications for the implementation of the African Green Recovery Action Plan. However, earlier in my career—specifically during the first ten years—I primarily worked as a journalist.

Mongabay: What inspired your interest in environmental issues? And why do you see journalism as an important tool for impact?

David Akana: My path shifted considerably in my fourth year in journalism, in 2002, when I joined IUCN in Central Africa to work on its radio initiative. While grappling with complex topics like biodiversity, forests, climate change, and carbon sequestration was difficult, I persisted. Part of my motivation was the financial security this role offered, along with the belief that I could make a significant difference in the environmental arena.

As I pursued additional training, including programs at the United Nations Environment Program and other specialized courses, my comprehension of the sector deepened. This period marked my shift from being a sports journalist and general reporter in Yaoundé, Cameroon, to focusing on environmental reporting.

Now, if you originate from places like mine—where I was born—with limited means for accountability or the ability to hold those in power responsible—you quickly realize that the media plays a vital role in raising awareness, fostering transparency, and improving the livelihoods of the people.

Mongabay: You mentioned transitioning from sports and general reporting to the environment. Was that shift purely driven by the opportunity at the radio station, or was there something deeper that drew you to environmental issues?

David Akana: We’re not always entirely strategic in every professional decision, are we? To be honest, at the time, it was a largely pragmatic choice. I genuinely enjoyed sports reporting—being around football players—a passion from childhood that continues even now. Cameroon’s football culture is globally renowned, so covering that beat was truly exciting.

But I ultimately joined IUCN partly because of the economic circumstances at the time, and also because of the opportunity to take on a leadership role in the newsroom, manage people, and challenge myself in a new field.

Once I was out in the field, I realized how high the stakes truly were. I found the work deeply meaningful and intellectually stimulating. The issues I encountered were complex and challenging, and that very complexity keeps me motivated to stay in this space.

Mongabay: So you made this transition from sports reporter to environmental reporter. With our fellowship program, one of the groups we’re targeting is exactly that kind of person—an existing journalist who may not know much about environmental issues but is curious and wants to move into the space. Do you feel the skills you had—as a sports journalist, for example—are widely applicable? In other words, could any journalist potentially become an environmental journalist?

David Akana: The answer is yes. I don’t consider myself inherently special, nor do I possess unique skills that other journalists don’t have. What I’m saying is that there’s nothing about me that made success in environmental reporting inevitable—anyone can thrive in this field with commitment and curiosity. While the environment is deeply rooted in science, succeeding on this beat is more about a willingness to keep learning and expanding your understanding.

Unlike sports reporting—which is often more straightforward—environmental journalism requires a different level of complexity. A drought story in Burkina Faso, for example, isn’t just about weather. It’s a climate story that touches on economics, migration, health, politics, agriculture, and even industrial activities happening as far away as California. Elevating your thinking to make those connections and asking the right questions to produce nuanced, balanced reporting is both challenging and rewarding.

Back in 2002, this wasn’t always obvious to me. But through years of learning, reading, and being willing to make mistakes, I’ve become much stronger and more confident on the environmental beat.

As laughable as it may seem now, I’m quite certain that some of my reporting and radio programs from 2002 were far from flawless. But the key isn’t to be ashamed of your early missteps—it’s to learn from them. The goal is to grow, so that next time, you speak with greater clarity, accuracy, and confidence.

Mongabay: You’re going into your third year leading Mongabay Africa. What have been the top lessons for you so far?

David Akana: First, having a focused strategy and being clear-eyed about your vision is essential for success. Without that, progress can become very challenging. However, a strategy alone isn’t enough—it’s equally important to remain flexible and make tactical adjustments as opportunities and challenges arise.

Second, you must continuously reconcile the desire to see your work create transformative change with the reality that some things simply take time. Today, journalism no longer has the immediate, “magic bullet” effect we once saw in early television days. Our credible content now competes in spaces filled with less serious material, often pushed by actors involved in greenwashing, disinformation, and misinformation. Patience, without losing sight of your ambitions, is key to staying motivated in this work.

Third, impact and influence take time. Environmental journalism, especially in underreported areas, often produces slow but lasting effects—shaping policies, empowering communities, and changing narratives—when done consistently and credibly. And it is a delight to see these impacts emerging from Mongabay work.

Fourth, maintaining a sustainable perspective is vital in everything we do. Much of what we do is geared toward long-term goals—whether nurturing the next generation of science writers or influencing policymakers and governments. Our work’s impact often materializes years later, which aligns with Mongabay’s focus on meaningful change rather than chasing clicks and views.

Lastly, adopting a positive mindset can make a significant difference. Africa presents many challenges—personally, I love the continent and am passionate about everything African. But even for the most optimistic among us, processing frequent negative news can be tough. For success in solutions journalism—an essential part of our strategy—you must constantly highlight local leadership, innovations driving change in nature’s frontlines in Africa, and positive policy developments, balancing these against reports on corporate misconduct or poor governance.

Mongabay: What do you look for when building a team?

David Akana: People who are different from me—in terms of perspectives, frameworks, life experiences, and cultures—are essential for a strong team. I prioritize diversity and inclusion, even as these words have become more controversial today. My goal is for my team to reflect the broad diversity of the African continent and the issues we cover in Mongabay Africa and across the entire world.

However, there are also some non-negotiables: I value brilliance and competence. If someone is truly brilliant—even if we disagree—I would still want them on my team. Lastly, I believe it’s important to find people who embrace the concept of teamwork—those who are less individualistic and genuinely enjoy collective success.

Mongabay: You’ve become a prominent leader as head of Mongabay Africa. What are your reflections on leadership?

David Akana: First, I am grateful for the opportunity to lead Mongabay Africa and I take this responsibility very seriously. When you consider Africa—its vast natural resources, many countries positioned along coastlines with immense trade potential, the vibrancy of its young, creative populations, and its large size—you might argue it should be one of the most developed regions on Earth. Yet, if you ask most economists, they’ll tell you that what Africa lacks most is strong leadership and good governance.

I have always understood that, regardless of the sector, without proper and effective leadership, progress will be difficult. When I took on the leadership of Mongabay Africa, I knew that leadership would be critical to its success. This involves mobilizing as many people as possible within the Mongabay ecosystem around a shared vision and building a team committed to turning that strategy into tangible results.

But leadership is more than just setting a vision—it’s about having the sensitivity to recognize that leadership doesn’t mean always having the last word or being right all the time. Effective leaders understand that they don’t decide everything; they foster collaboration and trust.

Finally, I see Mongabay not just as a job, but as a mission—to position the platform as the most influential player in ecosystem management in Africa over the next five or ten years. Driven by this long-term legacy, it becomes easier to stay focused, work toward those goals, and hopefully leave behind a legacy you can be proud of.

Mongabay: Let’s talk about impact. What’s been Mongabay Africa’s greatest impact so far—or what are you most proud of?

David Akana: Few countries in Africa require the media’s spotlight more than the Democratic Republic of Congo, especially when it comes to transparency. This country is so endowed with natural resources that, if managed well, it could unlock its true potential and position itself as Africa’s most developed nation in this century. Unfortunately, these resources have often become a curse, which is why I cherish every opportunity to help shape impactful reporting that highlights the repercussions of resource management. This is why I will share examples mostly from the DRC.

One recent example of our impact is a March 2024 investigation into the Alphamin Bisie tin mine in Eastern DRC—titled Under the shadow of war in the DRC, a mining company’s actions face impunity. This reporting continues to generate tangible ripple effects. Recently, a research associate at Artisan Partners, a global investment firm, contacted us as part of their risk assessment for potential investments in the region. They were leveraging our reporting to better understand reputational risks and local dynamics surrounding the mine. This followed Alphamin’s restructuring of its community engagement approach shortly after our initial story was published in 2024. It’s a clear example of how journalism can catalyze corporate accountability and bring overlooked community voices to the attention of global decision-makers.

There are several other notable investigations in the DRC, including our reporting on abuses within the extractive industry in the Congo Basin. These stories have not only raised awareness but also driven significant real-world impacts—such as influencing CITES authorities, EU import policies, and informing human rights investigations. Similarly, our 2024 investigation in Kolwezi, Lualaba Province, on the environmental and health impacts of mining has sparked local debate and garnered widespread attention, further fueling discussions on the industry’s effects on communities.

In the Republic of Congo, our six-month investigation into REDD+ schemes also garnered significant impact. The report, which critically examines how mining is displacing conservation efforts, was picked up by TV5 Monde and has been republished multiple times. When other media outlets report on your work, it speaks volumes about your impact and relevance.

We are witnessing similar ripple effects across West, Central, East, and Southern Africa.

Importantly, we are just getting started. One of my proudest achievements has been establishing the infrastructure for long-term success. We now have a full bureau with 17 full-time staff, a Swahili version of our platform in development, and a dedicated team of editors, writers, and feature reporters ready to do what Mongabay does best: investigate critical issues and provide nuanced coverage of the challenges facing Africa.

Mongabay: Looking ahead, is there anything you’re particularly excited about for Mongabay Africa? It could be something in the next year—or something in the next five.

David Akana: I see Mongabay emerging as the most influential media platform driving the conservation conversation in Africa. Its key constituents will not only be scientists, researchers, and development workers but also politicians. In my view, biodiversity and climate will be the most critical stories of this century. By 2050, the biodiversity and climate economy—and their influence on regional politics and decision-making—will surpass issues like health and education in regions such as the Congo Basin, shaping economic, financial, and political agendas more profoundly.

Building the foundation for this long-term success excites me the most. In the immediate future, connecting more deeply with local audiences—especially in East Africa, where over 180 million people speak Swahili—is a top priority. Currently, we report in English, French, and possibly in Portuguese someday. However, these languages tend to be elitist or spoken by minorities. Reporting in Swahili could be a game changer. Once we establish a strong presence there, we plan to explore other languages such as Hausa, Pidgin English, or Amharic. This is how Mongabay can succeed in Africa over the long term.

Africa is vastly misunderstood, including on conservation issues. Many believe Africans are poor stewards of their natural resources—yet, as an important conservation platform in Africa, Mongabay must help tell this story accurately. This involves developing diverse editorial programs that unpack Africa’s history, traditional knowledge, and cultural practices to ensure the world understands the continent’s conservation history, its relationship with colonialism and neo-colonialism, and its future direction. That, to me, is especially inspiring.

Finally, what excites me is producing different kinds of content that empower citizens across Africa to engage in meaningful debates and public dialogues on biodiversity, climate, oceans, pollution, and land degradation. Countries like Norway, Sweden, and other Scandinavian nations did not become environmentally conscious overnight—we know the media played a pivotal role. Mongabay, without advocating but through factual reporting, must continue to play a modest yet vital role—step by step—providing accurate information to help Africans better manage their vast resources, ensuring they benefit their people, and positioning the continent on a sustainable path toward wealth and prosperity in this century.

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for someone who wants to become an environmental journalist in Africa?

David Akana: Deciding whether to pursue a career as an environmental reporter can never be separated from the realities of journalism’s economics, which remain challenging across the world—particularly in Africa. Additionally, safety and security issues are a major concern, especially in Africa, where many governments oppose openness and transparency, often hiding information. With limited freedom of information laws, working under such conditions becomes even more difficult. Yet, there is no greater reward than seeing your work contribute to change or being recognized for influencing people’s lives—wouldn’t you agree?

Every journalist must make that personal call about whether they’re willing to work in these circumstances. I am deeply convinced that many successful journalists see their work as something larger than themselves—a mission driven by purpose and conviction. That’s often the only way someone would risk imprisonment or even their life to tell the truth.

That’s what’s at stake, and I encourage anyone seeking a meaningful mission to join us in telling the stories of this century. In Africa, that mission means speaking or writing about the silent majority, often living on the margins of poverty, and giving voice to those on nature’s frontlines who are often unable to benefit from their own resources.

Being an environmental reporter in this context is incredibly meaningful and rewarding – that is my only advice. This is why I have tremendous respect for Mongabay Africa journalists and the network of contributors reporting from some of the most challenging regions.

Mongabay: Another general question: What motivates you?

David Akana: Let me share an example of what excites me: recently, I was in the Southeast region of Cameroon for some reporting. There, we met many people living around the Lobéké National Park. When you map out the key stakeholders in the area, you see that many are relatively wealthy—including funders of conservation activities in the park, some of whom reside thousands of miles away in Europe and North America. Others hold political power, such as officials based in Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, who make most of the decisions regarding protected areas. Additionally, there are owners of logging companies that operate around the parks. For the most part, these actors are well-connected, powerful, and always get their interests served.

Beyond these actors, there are also the Baka—the indigenous community living in the area—as well as Bantus. I spoke with most of these stakeholders. When questioning individuals from these communities about their involvement in decision-making, it quickly becomes clear that there is an imbalance of power. In such cases, only the media can help address some of these injustices by raising awareness and bringing these issues into the public discourse through reporting.

That’s what excites me the most—serving as the voice of the voiceless.