How to reduce the environmental impact of using AI

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

How to reduce the environmental impact of using AI

One of the biggest concerns over the use of generative AI tools like ChatGPT is their environmental impact. But what is that impact — and what strategies are there for reducing it? Here is what we know so far — and some suggestions for good practice. What exactly is the environmental impact of usingGenerative AI? It’s not an easy question to answer, as the MIT Technology Review‘s James O’Donnell and Casey Crownhart found when they set out to find some answers.Challenges include the variety of language models (LLMs) used by different platforms, the lack of transparency from providers, and differences in the energy grid (e.g. the mix of renewables and fossil fuels) and cooling methods used. It is also a constantly changing picture: early, widely cited, estimates of chatbot energy usage are now understood to have overestimated the figure. The average energy efficiency of hardware used by AI systems improves by about 40% annually, and less water-intensive cooling systems are also being explored.

What exactly is the environmental impact of using generative AI? It’s not an easy question to answer, as the MIT Technology Review’s James O’Donnell and Casey Crownhart found when they set out to find some answers.

“The common understanding of AI’s energy consumption,” they write, “is full of holes.”

Challenges include the variety of language models (LLMs) used by different platforms, the lack of transparency from providers, and differences in the energy grid (e.g. the mix of renewables and fossil fuels) and cooling methods used.

It is also a constantly changing picture: early, widely cited, estimates of ChatGPT’s energy usage are now understood to have overestimated the figure. DeepSeek demonstrated that AI could be developed in a much more energy-efficient way, and smaller models are now as effective as the large models launched two years earlier. The “average energy efficiency of hardware used by AI systems improves by about 40% annually“, and less water-intensive cooling systems are also being explored.

Against those downward forces, however, are trends that can intensify energy costs: genAI models are still getting bigger (using more energy) and the Jevons paradox suggests efficiency often simply leads to increased consumption.

How much energy does a genAI query use?

O’Donnell and Crownhart’s reporting estimated that energy used by a prompt ranged between 57 joules (for prompts using a small model) and 3,353 (for a large one), or 114-6,706 joules “when accounting for cooling, other computations, and other demands”.

Josh You‘s estimate for Epoch AI of 1,080 joules, or 0.3 watt-hours (Wh), for ChatGPT queries — equivalent to using a laptop or lightbulb for five minutes — sits at the lower end of that range, while a recent preprint introducing an “infrastructure-aware benchmarking framework” for measuring environmental impact of AI models puts the figure at 1,548 joules (0.43 Wh).

Dr Marlen Komorowski warns against “eco-shaming” around the use of AI, comparing coverage to previous stories on new technologies:

“In the early 2010s, data centers themselves faced dire predictions [then] headlines abounded about Bitcoin’s colossal electricity usage – sometimes rightly so … and it spurred change … Those worst-case scenarios didn’t materialize – thanks to huge improvements in efficiency [and use of renewables]”

She argues that the focus on individual use of technology can be misplaced, repeating a tactic popularised by BP with the ‘carbon footprint’ calculator, “implicitly telling us that climate change is due to our individual choices”.

Reflecting on his own reporting on the environmental costs of generative AI, James O’Donnell comes to similar conclusions:

“It’s likely that asking a chatbot for help with a travel plan does not meaningfully increase your carbon footprint. Video generation might. But after reporting on this for months, I think there are more important questions. “Water being drained from aquifers in the country’s driest state to power data centers that are drawn to the area by tax incentives and easy permitting processes. Or how Meta’s largest data center project is relying on natural gas despite industry promises to use clean energy. Or the fact that nuclear energy is not the silver bullet that AI companies often make it out to be.”

Learning from other experiences

In 2019, when Le Monde launched a video series about climate issues, they “realised there was an inherent contradiction in the fact that we would be reporting about the climate crisis, but taking loads of flights to do so,” Charles-Henry Groult, Head of Video at Le Monde, told Reuters Institute.

The organisation used the opportunity to assess the environmental impact of their reporting:

“Each time a journalist travelled for a story, they would input [on a spreadsheet] the distance travelled and the transport method used (“Paris to Marseille, 750 kilometres, via TGV train”) to estimate the carbon footprint of the trip. They also added a column with a rough calculation of the carbon emissions that a day of shooting video and a day of editing would produce. They then listed the ‘carbon cost’ of each story in the video credits.”

After a year of monitoring, they established new policies for reporting, including not taking flights within the country, and using public transport within the city.

The comparisons between AI energy usage, laptops and lightbulbs are instructive: it’s not just ChatGPT that comes with an environmental cost (streaming video, for example, is especially energy-intensive, yet not nearly discussed as much) — and reporters and organisations already have experiences in addressing this.

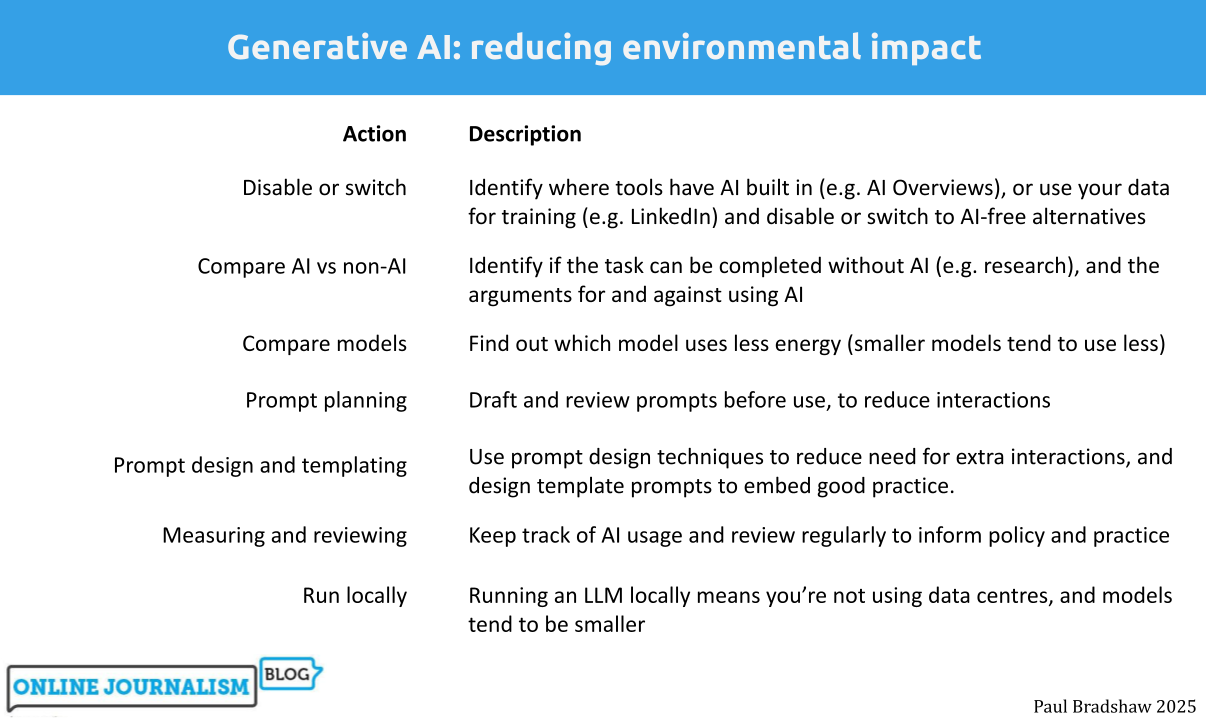

Start with a clean sheet: opt out of training, turn off automatic AI, or change tool

A simple first step to reducing the impact of using AI is to turn off the increasingly built-in activation of AI functionality. Disabling Copilot in Microsoft, for example, the AI assistant in Adobe, or Google Sheets’s AI-powered autofill.

For security reasons as well as environmental ones, you may want to opt out of your data being used for AI training. Matt Burgess’s Wired guide to stop your data being used to train AI lists the various platforms — from Adobe and Amazon to Rev and LinkedIn — where you need to opt out.

In some cases it’s not possible to turn features off. Google’s AI Overview search results, for example, can only currently be disabled through a URL hack. If you don’t want your search results to include AI generated summaries, then, your best option is to switch to a search engine like DuckDuckGo which allows you to turn off AI.

Weigh up the pros and cons of using AI for a task

Just because you can use AI, doesn’t mean you should: for many tasks, a non-AI method is still ‘good enough’.

A good example is research — one of the most widely-used applications of AI. Many questions asked via ChatGPT can be answered just as well, or even better, through a search engine, a book, email or phone call.

If your question requires particular types of sources, then AI might not be the best tool for the job, as it is poor at distinguishing between expertise and amateurs.

AI responses to a search question can also be unreliable and poor quality, especially if there is very little information online (in its training data). Consider how much extra time may be required for verifying AI responses, as this can render it less efficient research tool.

Image generation is another area where alternative options may be better. For example, you might only use AI tools where the image you need is unlikely to exist (like a hallucinating elephant).

Video generation with AI is on a whole other level when it comes to the energy costs: a video as short as five seconds uses 42,000 times as much energy as a text query — “enough to power a microwave for over an hour” according to O’Donnell. That might still be less than the combined impact of a full video production — but if the alternative was a static image, is it really worth it?

Skill up: learn prompt design techniques

Knowing basic prompt design techniques can massively reduce the number of prompts you will need to use in a tool like ChatGPT — and therefore, the environmental impact.

Some prompt design techniques are more resource-intensive: recursive prompting, for example, involves improving the quality of responses through a series of follow-up prompts that provide feedback on previous responses, and so it can result in more interactions than might be necessary.

Negative prompting, in contrast, involves setting limits on what the AI model does, and so is likely to reduce generative AI’s tendency to do more than you’ve asked, and use more words than are necessary.

Some techniques might initially be more resource-intensive but save energy in the long run.

RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation), for example, involves ‘augmenting’ your prompt with extra information such as text pasted from your research, or a document or data. Processing that information takes extra energy — but if it reduces the number of prompts and responses overall (by producing usable results earlier), then this can be more efficient.

The same applies to Chain-of-Thought (CoT) and n-shot prompting: by specifying the steps you want the model to take (CoT) or providing examples (n-shot), it uses more energy — but if it reduces the number of prompts needed to get to a usable result, then it may be a better strategy.

Plan and template your prompts (minimise iteration)

Once you’ve learned prompt techniques, you can start to plan prompts.

Drafting prompts outside of the genAI tool, and reviewing them to ensure they are as effective as possible, is another step to reducing the amount of energy used within genAI tools.

Where AI is used repeatedly for similar tasks, it is worth considering templating certain prompts: this means identifying and embedding best practice in a template prompt that colleagues can adapt to their own particular purpose, again ensuring that fewer prompts are needed to get to a usable result.

Use a smaller model

Each AI platform uses a different large language model — and those models regularly change. Last month, for example, Claude switched to a new model.

Each model uses different amounts of energy, so it’s worth trying smaller models (which tend to be less energy intensive) to see if they work for you.

To see which model is currently being used, look in the upper left corner (ChatGPT and Gemini) or under the text box (Claude). You can click on the current model to select a different model. Some will only be available if you have a paid account.

Frustratingly, research attempting to benchmark different models does suffer from a time lag. So, for example, it’s possible to know that Claude 3.7 Sonnet probably uses less energy than 3.5 — but not how either compares to the newly released model. And new announcements don’t typically include this information.

What we can see is that GPT-4o (the current ChatGPT model) appears to consume less energy than Claude’s models, and Meta’s Llama model is more efficient than either.

If you are able to download a model and run it locally, then that will also reduce your environmental impact — and open up more models. The Hugging Face leaderboard offers an ongoing comparison of (typically lesser-known) models’ energy use across different use cases. You can also test or download older, smaller models such as GPT-2.

Stop being polite

tens of millions of dollars well spent–you never know — Sam Altman (@sama) April 16, 2025

A final simple way to reduce your environmental impact is to avoid being nice to our new robot overlords. Earlier this year the OpenAI CEO Sam Altman admitted that using “please” and “thank you” in prompts led to extra costs for the company.

Do you have any tips on reducing the environmental impact of AI usage, or techniques for deciding when to use it? Please share them in the comments or on LinkedIn @paulbradshawuk.

Source: https://onlinejournalismblog.com/2025/06/19/how-to-reduce-the-environmental-impact-of-using-ai/