Sled dog genetic history sheds light on human migration patterns into Greenland

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Sled dog genetic history sheds light on human migration patterns into Greenland

The Greenland sled dog, or Qimmeq (plural Qimmit), is one of the few breeds that can still be found pulling a sled. They have been much more isolated genetically than other traditional sled dogs and are now facing a decline in population. Their numbers have been halved since 2002, going from a population of around 25,000 to about 13,000 in 2020. Researchers sequenced 92 Qim meq genomes from the past 800 years and compared them with 1,998 genomes from ancient and modern dogs and wolves. The genomes were separated into three groups from different periods: pre-European contact from when the Inuit arrived in Greenland until the Danish-Norwegian colonization (between 1721 and 1884), post-Europeancontact (from 1885 to 1998) and present-day (after 1998) These separations helped to determine the impact and extent of European contact in Greenland. The results of the study, recently published in Science, showed two distinct migrations into Greenland.

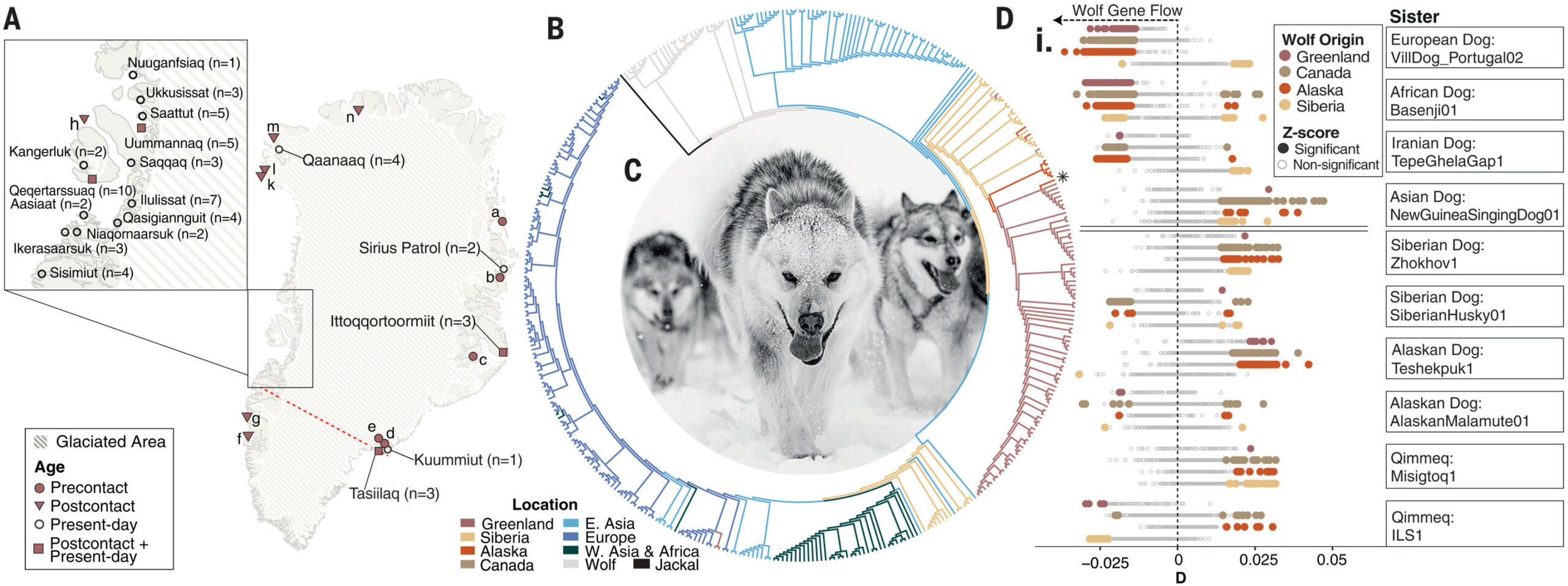

Relationship of Greenland dogs to global dogs. Credit: Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adu1990

The histories of sled dogs and humans in the Arctic have been intricately linked for thousands of years, so it is no surprise that the migration patterns of these dogs mirror those of humans through the Arctic. Sled dogs have assisted humans with the difficult tasks of traversing through harsh environments and transporting heavy materials and food, ultimately playing an important role in survival. However, many breeds of sled dog, like the Siberian husky, Alaskan malamute and Samoyed, have now mostly transitioned out of their traditional roles and into the role of pets and are often mixed with other breeds.

The Greenland sled dog, or Qimmeq (plural Qimmit), is one of the few breeds that can still be found pulling a sled. They have been much more isolated genetically than other traditional sled dogs and are now facing a decline in population, due to reduced Arctic ice, urbanization, competition from snowmobiles and general changes in the lifestyle of Arctic people. Their numbers have been halved since 2002, going from a population of around 25,000 to about 13,000 in 2020.

This dramatic decline, along with the fact that the Qimmit have been working alongside humans for so long, prompted researchers at the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes for Health to take a deep dive into their origins and genetic diversity to shed light on their history and the history of the people around them.

The researchers sequenced 92 Qimmeq genomes from the past 800 years and compared them with 1,998 genomes from ancient and modern dogs and wolves. The genomes were separated into three groups from different periods: pre-European contact from when the Inuit arrived in Greenland until the Danish-Norwegian colonization (between 1721 and 1884), post-European contact (from 1885 to 1998) and present-day (after 1998). These separations helped to determine the impact and extent of European contact in Greenland.

The results of the study, recently published in Science, showed two distinct migrations into Greenland. Genetic markers found in the Qimmit place their arrival in Greenland around 1000 years ago—earlier than previously thought. A close relationship between the Qimmit and an Alaskan breed, dating back to around 3,700 years ago, suggests that the Inuit left this region and migrated across the Arctic Circle relatively rapidly.

Population structure of Greenland dogs. Credit: Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adu1990

Interestingly, the study indicates the possibility that the Inuit arrived in Greenland before the Norse people—although they may not have interacted much. The study authors write, “After 985 CE, it is known that Norse settlements were established in southwestern Greenland, but the degree of interaction between the Norse and their Inuit contemporaries remains unclear.”

The Inuit people and their sled dogs also seemed to have remained genetically isolated from the Danish and Norwegian people after their colonization, as the study found minimal European ancestry in present-day Qimmeq genomes. However, the study did reveal changes in the regional diversity of the Qimmit after the Danish-Norwegian colonization. A divergence of Qimmeq populations into distinct regional groups occurred in the same manner that the indigenous peoples of Greenland split up into more distinct subcultures in different parts of Greenland.

Overall, this new evidence displays the close relationship between the Inuit and their sled dogs, as well as their cultural importance. It also provides valuable insight for conservation strategies to preserve the Qimmit populations in the face of climate change and globalization.

Written for you by our author Krystal Kasal, edited by Gaby Clark, and fact-checked and reviewed by Andrew Zinin—this article is the result of careful human work. We rely on readers like you to keep independent science journalism alive. If this reporting matters to you, please consider a donation (especially monthly). You’ll get an ad-free account as a thank-you.

More information: T. R. Feuerborn et al, Origins and diversity of Greenland’s Qimmit revealed with genomes of ancient and modern sled dogs, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adu1990 Journal information: Science

© 2025 Science X Network

Source: https://phys.org/news/2025-07-sled-dog-genetic-history-human.html