Triumph of Mariner 4

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

‘Triumph of Mariner 4’

Sixty years ago, NASA’s Mariner 4 became the first spacecraft to fly by Mars. Its pictures of a barren, cratered surface snuffed out notions of little green men and alien civilizations. Speculation about what might be happening on Mars flooded popular culture from the 1800s into the late 20th century. Some visitors from the Red Planet appeared benevolent, architects of advanced civilizations. Another view posed Mars as a threat — a war-like expansion, like that of H.G. Wells’ “The War of the Worlds’ (1898). In the end, the Martians’ own planet was dying up, so they “regarded this planet as their own, so dying up so they didn’t want to share their technology with it’ . In the public imagination, canals meant industry and civilization. American astronomer Percival Lowell championed the belief in canals, telling the New York Times in 1907 that Mars is “at present the abode of intelligent, constructive life.”

For as long as humans have looked up, Mars has beckoned.

A pale orange point of light, unlike anything else in the night sky. A glowing cinder, floating above the campfire. Tantalizing, but out of reach. What’s up there? What does it look like — up close?

No one could know for sure, even using the finest instruments and telescopes on Earth, when peering from 35 million miles away (at its closest).

But we kept trying, even for just a glimpse.

How we used to see Mars:

1610: Galileo Brings Mars Closer

1888: Canals on Mars?

1908: Mars, Abode of Life

1900s: Mars, Bringer of War

Mars 1956 1610: Galileo, Cassini Bring Mars Closer Galileo was the first to view Mars through a telescope, in 1610. Italian astronomer Giovanni Cassini observed the southern polar ice cap, and measured the length of the Martian day accurately to within three minutes, in 1666. In the centuries that followed, others sketched what they saw through ever-improving optics, and according to the Globe Museum of the Austrian National Library, the surface of Mars had been completely mapped by 1841.

Completely — perhaps. Accuracy was still a work in progress. View Image An 1897 Mars globe by French astronomer Camille Flammarion, in cooperation with Eugène Michel Antoniadi, a Greek-French astronomer, displayed at the Globe Museum of the Austrian National Library in Vienna. The globe shows canals, but Antoniadi later became a canal skeptic, after observing Mars in 1909 with the then-largest telescope in Europe. 1888: Canali on Mars Giovanni Schiaparelli, another Italian astronomer, drew long, linear features he spied on the surface, calling them canali — Italian for channels, or gullies. They were later determined to be optical illusions, but not before mis-translations branded them canals. The Suez Canal had opened in 1869, and work on the Panama Canal began in 1881 — in the public imagination, canals meant industry and civilization. View a vintage map of Mars from 1888 A map of Mars made by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1888. Objects appear inverted when seen through a telescope, so the South Pole is on top. (Schiaparelli called the linear features he observed canali, which is Italian for “channel,” and he made no inferences about their origin; the word was mistranslated into English as canals, which was then misinterpreted as evidence of intelligent life. Later observations showed the lines were optical illusions.) Giovanni Schiaparelli, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Mars, the Abode of Life American astronomer Percival Lowell enthusiastically championed the belief in canals, telling the New York Times in 1907 that Mars is “at present the abode of intelligent, constructive life. …No other supposition is consonant with all the facts here.” In addition to bankrolling a world-class observatory so he could study Mars — his namesake facility in Arizona — Lowell wrote three popular books on the Red Planet: Mars (1895), Mars and Its Canals (1906), and Mars as the Abode of Life (1908). He reasoned that Martians were peaceful, given the cooperation required to build a worldwide canal network.

What if they weren’t peaceful? What would that be like? Writers such as Edgar Rice Burroughs and H.G. Wells had some ideas. Read More Percival Lowell with the Lowell Observatory staff at the Clark Telescope in 1905. Left to right: Harry Hussey, Wrexie Louise Leonard, Vesto M. Slipher, Percival Lowell, Carl Lampland, and John C. Duncan. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Mars, Bringer of War Speculation about what might be happening on Mars fueled public imagination, so Martians flooded popular culture from the late 1800s into the 20th century — in books, movies, radio plays, music, advertising.

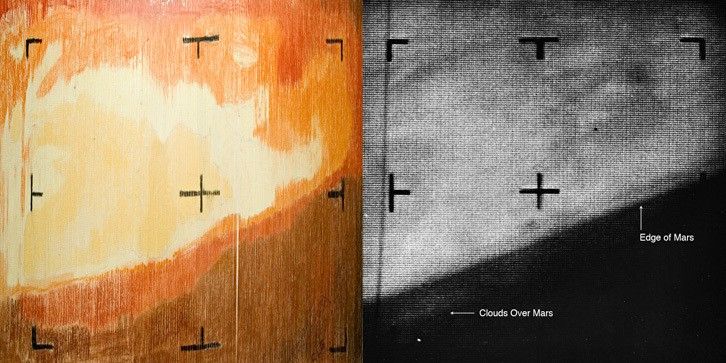

Some visitors from the Red Planet appeared benevolent, architects of advanced civilizations, even willing to share their utopian ideals and advanced technology. Another view posed Mars as a threat — warlike, expansionist, inhuman — a theme spawned by H.G. Wells’ “The War of the Worlds” (1898). In that, the Martians’ own planet was drying up and dying, so they “regarded this Earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.” See Image Martian fighting machine in the Thames Valley, from “The War of the Worlds” by H.G. Wells. Illustration by Henrique Alvim Corrêa, from the 1906 Belgium (French language) edition. Henrique Alvim Corrêa, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Our Best View of Mars, 1956 Before Mariner 4 visited Mars, even the best telescopes on Earth gave us only faint glimpses of the Red Planet Alien-invasion movies of the 1950s had more to do with a different Red Scare than any fear of Mars. But yearning for canals, or any other details we could see, persisted. Our own turbulent atmosphere gets in the way, though.

In September 1956, Mars made its closest approach to Earth since 1924, passing only 35.1 million miles away (about 56.49 million kilometers). For this “opposition,” when Mars and the Sun would be on opposite sides of Earth, and the Red Planet would be at its closest and brightest, Earth-bound astronomers trained their telescopes on Mars. Among the best: the 100-inch telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory in Southern California; it’s the instrument Edwin Hubble used to prove that our Milky Way galaxy is not the extent of the universe, but merely one of millions of galaxies in a vast, ever-expanding cosmos.

At right, the best view it offered of Mars, the planet next door. See Image Astronomers took these images of planet Mars through the 100-inch telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California,1956. The Carnegie Institution for Science

Then, one image changed everything:

Picture No. 11 of the Mariner sequence must surely rank as one of the most remarkable scientific photographs of this age. Robert B. Leighton Mariner 4 Principal Investigator, Caltech, speaking at the White House July 29, 1965

Mariner 4: Image No. 11, Mariner Crater This photo clearly showed craters upon craters, and nothing else — a “scientifically startling fact,” according to the Mariner imaging team. They saw a desolate landscape that had scarcely changed in 2 to 5 billion years, an environment more like the lifeless Moon than any place on Earth.

They called the revelation “profound,” not just for what it suggested about Mars’ past and present, but because it “further enhances the uniqueness of Earth within the solar system.” Mariner 4: Image No. 11, Mariner Crater

No canals, but a path forward

Mariner flew above areas where canals had been drawn, and saw none. If the cratered, barren, untouched surface disappointed some observers, many scientists saw an opportunity. If these areas had gone undisturbed for 2 billion years, they could one day reveal what rocky planets such as Earth were like, in their first couple billion years of existence — clues that had long since been wiped from Earth’s surface by plate tectonics and other processes.

And even if Mariner revealed no signs of life on Mars, they believed Mars could one day serve as a time capsule, showing how life arose on Earth. “If the Martian surface is truly in its primitive form,” the Mariner team said, “that surface may prove to be the best — perhaps the only — place in the solar system still preserving clues to original organic development, traces of which have long since disappeared from Earth.”

Those are the same clues the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers are searching Mars for right now — signs of past life.

Success, even before the photos

Two days after the flyby, when only one of 21 complete images from Mars had arrived, the New York Times published an editorial, “Triumph of Mariner 4,” which said, “it is already clear that Mariner 4’s historic journey to Mars is the most successful and most important experiment man has yet conducted in space, as well as one of the most brilliant engineering and scientific achievements of all time.”

Mariner 4 was not just there for snapshots. Its other instruments revealed that the atmospheric pressure on Mars was less than 1% that on Earth’s surface — too low for liquid water to exist. And Mars had no discernable magnetic field, unlike Earth, so no protection from a deadly barrage of solar and cosmic radiation. Mars was proven to be hostile — but to life on its own surface, not to anyone on Earth.

‘Color-by-Numbers’ Mars The first digital image from space was a handmade craft project Mariner 4 began capturing its images of Mars at 8:18:49 p.m. EDT on July 14, 1965. It finished about 25 minutes later, but the mission team still had many more hours to wait before seeing the finished product. Too eager to wait, some of them decided to skip ahead. What’s taking so long? Every image that Mariner captured took about eight hours to reach Earth, faint signals beamed 134 million miles to the enormous radio dish antennas of NASA’s Deep Space Network, in South Africa, Australia, and Goldstone, California. Those stations relayed the data to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. For each image that Mariner’s camera captured, 200 pixels wide and 200 lines deep, the spacecraft assigned a number to every one of those 40,000 pixels based on its shade of gray — a scale from 0 (white) to 63 (black). When that string of numbers reached JPL, teletype machines printed page after page of the figures. Meanwhile computers processed the data, converting the digits back to shades of gray, and piecing together the full images. From the numbers coming over the teletype, the mission team at least knew Mariner was sending data. But some engineers couldn’t wait for that first image. They wanted to make sure all the equipment had worked properly, and that the numbers coming from Mariner 4 were correct, and would translate to actual images. Plus, they were just eager to see Mars. They took the teletype printouts of the numbers representing the first image — row upon row of digits — and cut those into strips. They stapled the strips to a wall, lining them up in the correct order to recreate the 200×200 pixel image. Engineer Richard Grumm bought a set of pastels from a local art store to shade the ranges of numbers on their printouts; they hoped to emulate what the first image would look like, when the computers finally finished their processing. The team also created a color chart, to get their shading right. “We created an image that way on paper, faster than they could reconstruct a picture in the computer,” said JPL’s John Casani, then Mariner 4 spacecraft systems manager. With each image taking more than eight hours to download and process, for all of the images Mariner 4 captured (21 complete and one partial), it took 10 days to transmit the data to Earth and convert it into the black-and-white pictures. By then, only the first three were made public. The remainder were released at a White House ceremony on July 29. Finished artwork, and the real thing In their haste to see data translated into a usable image, the engineers inadvertently created a work of art. So they cut it from the wall and presented it to JPL Director William Pickering. Today — properly framed and preserved — it hangs outside the visitors’ gallery at JPL’s historic High Bay 1, the cavernous clean room where Mariner 4 had been assembled, as were all five of NASA’s Mars rovers, and numerous other historic spacecraft.

photo sharing, across 134 million miles The First Mars Close-Up Photo This documentary clip shows the Mariner 4 team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, waiting for computers to process the data sent from the spacecraft back to Earth, turning that into an image, and then the moment they see the picture they had been waiting for. Watch the Full Documentary, ‘JPL and the Space Age: The Changing Face of Mars’ To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

The 21 full images from Mariner 4 were historic, a view of Mars that humans had been straining to see for centuries, if not longer. But the images covered only 1% of the planet’s surface — a fleeting glimpse.

We needed to see more. We needed to go back. So we did.

back to mars The Missions that Followed Mariner 4, and What They Showed Us The NASA missions that succeeded Mariner 4 — making their own history in Red Planet exploration — have delivered images and insights only dreamed of in 1965. Since then, and through today, orbiters, landers, five different rovers, and even a tiny helicopter have traversed Mars — continually teaching us more about the Red Planet, about the origins of our solar system and our world, and whether life has ever existed someplace other than Earth. Read: ‘Advances in NASA Imaging Changed How World Sees Mars’ The global mosaic of Mars was created using Viking 1 Orbiter images taken in February 1980. The mosaic shows the entire Valles Marineris canyon system stretching across the center of Mars. It’s more than 2,000 miles (3,000 kilometers) long, 370 miles (600 kilometers) wide and 5 miles (8 kilometers) deep. NASA/USGS

Source: https://science.nasa.gov/mars/triumph-of-mariner-4/