Video Weight loss medication and heart health

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

Deepfake videos of Norman Swan are tricking people into buying unproven supplements at a risk to their own health

Fake Norman is currently out there spruiking four unproven products that I know of. The fake videos link to a website for the unproven supplement Keto Flow + ACV. They have little or no scientific basis to back up the marketing claims, but the sales pitch is far from benign. David Bell stopped taking his prescribed medication based on advice from a convincing fake ad. 730 has found three registered businesses linked to Glyco Balance. They appear to be connected to a global company, Pty Pty Velle Ltd, on the Gold Coast and the Christchurch Gold Coast, and to a company on the NSW South Coast. The company’s website is www.ptypty.co.uk/glyco-balance and the company’s Twitter account is @GlycoBalance. For confidential support call the Samaritans on 08457 90 90 90 or visit a local Samaritans branch, see www.samaritans.org for details. In the U.S. call the National Suicide Prevention Line on 1-800-273-8255.

Listeners, viewers, friends, colleagues and family started to contact me, all with roughly the same question, then and now:

“Is this ad I’ve seen with you in it real? And should I buy the product?”

What they had seen was a video or article, via Facebook or Instagram, which featured me flogging supplements or weight loss products purporting to treat heart disease, diabetes or obesity.

Loading…

I was often denigrating the medical profession and calling the prevailing scientific wisdom “stupid”.

When the first ones appeared I asked the ABC to see if they could have them taken down. That didn’t work.

Then this year these fake ads started again. They were much more sophisticated and in much larger volumes.

Loading…

Fake Norman is currently out there spruiking four unproven products that I know of.

The fake videos link to a website for the unproven supplement Keto Flow + ACV. (Supplied)

One AI-generated video which keeps appearing on Facebook features Rebel Wilson talking about losing weight thanks to a new supplement recommended by “Dr Norman Swan”.

Another deepfake follows the same format but with singer Adele. These deepfakes link to an external website for an unproven weight loss product called Keto Flow + ACV.

Another pernicious scam involving me is for an unproven product called Glyco Balance.

Both Glyco Balance and Keto Flow + ACV are allegedly made from “all natural” ingredients (although the ingredients list changes depending on what website you visit). They have little or no scientific basis to back up the marketing claims, but the sales pitch is far from benign.

Dangerous health advice

David Bell stopped taking his prescribed medication based on advice from a convincing fake ad. (ABC News)

David Bell lives in a retirement village in the northern suburbs of Melbourne.

He is well-educated — his hobby is translating Russian poets of the 19th and early 20th centuries into English — but David’s health is poor and he has diabetes.

When an article supposedly penned by me popped up on his laptop it got his attention.

A fake ad featuring Norman Swan.

“I thought, ‘this is interesting. I wonder what Norman’s got to say about diabetes’,” he told me.

“It was compelling. And what it was saying was that there is … a chemical called metformin, and it is not beneficial to the body. You should stop taking it.”

Metformin is one of the core drugs used to treat type-2 diabetes and is effective in helping to prevent diabetes complications such as blindness and kidney damage.

The article encouraged diabetes patients to stop their metformin and start taking Glyco Balance instead.

The article was so convincing that David ceased his prescribed medication.

“I’m angry with myself for having fallen for it but you’re an authority,” David told me.

“You’re a well-known figure in the health service. Why would I not believe you?”

Late in 2024, another ad for Glyco Balance with similar content appeared on Meta platforms.

This time, instead of me, it was an AI-generated video of leading diabetes researcher and specialist Jonathan Shaw, of the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne.

Loading…

It was this deepfake that drew in Adelaide resident Janis as she sought to lose weight.

“I researched him … and saw that he was really high up in the heart and diabetes [medical space] in Australia,” she told 7.30.

“So I thought, ‘Wow this guy’s put this product together. It’s Australian. I’ll give it a go.'”

When Janis’s order arrived, the dose on the bottle was 204 milligrams, but the advertised amount was 800mg.

Her bank account also had more than $300 removed instead of just over $200 and eventually Janis discovered that the company had put in place a monthly debit of more than $300 without her being aware of it.

Even with all that, she did try the supplement to see what happened.

“Actually, as far as I’m talking about losing weight … I put on a few kilos while I was taking the first bottle,” Janis told 7.30.

Tracking those responsible

Glyco Balance is an unproven weight loss supplement. (Supplied)

7.30 has found three registered businesses linked to Glyco Balance and Keto Flow + ACV: Vellec Group NZ Ltd, Healthy Life Choices NZ Ltd and Apex United Pty Ltd.

They have offices in Christchurch and the Gold Coast, and appear to be connected to a global company based in the US.

They use the same sales and marketing playbook, the same website layout and the same deceptive tactics to lure in consumers.

7.30 has found that some of the people involved in running these companies are related to each other.

Numerous customers all have the same complaints about both products. Namely: people are being overcharged and signed up to a monthly auto-debit without their permission.

7.30 has emailed and phoned the companies involved and contacted their Auckland-based accountant. Apart from one person denying he had anything to do with the business despite being the sole registered director, we have had no other responses.

Since the businesses have been contacted, the main order pages for Glyco Balance have been taken down.

Affiliate websites now redirect customers to order pages for “Glucovate” and “Glyco Forte”.

This page featuring testomials for Glyco Balance was taken offline. (Supplied)

Customers are now being redirected to a page for Glucovate, which features near-identical reviews. (Supplied)

A search through internet archives reveals other name changes the product has undergone in the past, including Blood Balance — the version I was first deepfaked in relation to 18 months ago.

How deepfakes are made

These fakes are remarkably easy to make.

“You need a laptop, internet connection, access to some free or paid software, so it’s not a capital-intensive business,” said Sanjay Jha from UNSW’s School of Computer Science and Engineering.

He and his student Wenbin Wang have developed an artificial intelligence model for teaching purposes. They showed us how the scammer likely created my deepfakes.

Professor Sanjay Jha and student Wenbin Wang have created a “deep learning” model that can create AI-generated versions of teachers. (ABC News: Jerry Rickard)

The scammer starts with a video of me, taken from a platform like YouTube. They then upload it to a deepfake program that can be purchased for a few dollars.

First, my voice is cloned from a sample which can be as short as a few seconds. The AI model then clones my appearance, scanning the video of me frame by frame, mapping my face from various angles. Then the scammer can type in what words they want me to say.

Meta’s ‘get out’ card

When Professor Shaw began to receive emails and calls from people wanting to stop their medication or wanting to know where they could get the supplement, he knew there was an issue.

The real Professor Jonathan Shaw struggled to get the fake ads taken down. (ABC News)

His initial attempts to get Meta to take down the fake ad got nowhere until the Baker Institute’s lawyers advised Meta there had been a breach of trademark and intellectual property.

That is when they got a response and had the scam taken down. But new versions kept on appearing.

The ABC has also had trouble getting the attention of Meta.

Rod McGuinness is the ABC’s social community lead and coordinates the ABC’s presence on social media. He has had over a dozen ABC personalities used by scammers, including Karl Kruszelnicki, Alan Kohler, Michael Rowland and Virginia Trioli.

Rod McGuinness has been frustrated by Meta’s response when he’s contacted them about fake ads. (ABC News: Jerry Rickard)

“We spend a lot of time, or certainly have over the years, reporting these things, saying to Meta, ‘can you do something about this?’ And very often there’s no response,” McGuinness told 7.30.

In 2024, Meta made over $US164 billion, most of which was advertising revenue. Scammers exploit Facebook and Instagram’s algorithms, targeting vulnerable consumers via paid posts.

Up until now, Meta has largely shirked responsibility. Mr McGuinness says he has been frustrated by its lack of responsibility.

Meta says it has been proactive in taking deepfake ads down. (Reuters: Manuel Orbegozo)

“Facebook have always said they’re not publishers — it’s the people that use Facebook that are the publishers,” he said.

“And I think in this context that’s quite a nice get out because they can say, well, we don’t control these things. However, they are happy to take the ad revenue.”

Nathaniel Gleicher is the director of security policy and global head of counter fraud at Meta. He says the organisation faces a significant challenge.

“We’re talking about sophisticated operations working at industrial scale, often backed by criminal organisations that are highly resourced … and are looking to target people wherever they can find them,” Mr Gleicher said.

Nathaniel Gleicher is the global head of counter fraud at Meta. (Supplied)

“They’re very quick to adjust their tactics to defeat any defences you put in place.”

He also maintains that Meta has been highly proactive in its approach to deepfake scams.

“In the fourth quarter of 2024 we removed more than a billion fake accounts and, 99.7 per cent of those, we removed proactively before anyone noticed them,” he said.

But a miss rate of 0.3 per cent in more than a billion accounts means there are still a lot of scams slipping through.

“One of the real challenges is that these scams abuse multiple systems,” Mr Gleicher said.

“The scammer starts by creating a fake bank account to receive the money — they often need a warehouse to store the actual products that they might be shipping [then] they will move people to a website on the open internet, and then, obviously, they’re using an instant payment system.

“To counter this, you really need each of these communities working together.”

Aussie lose more than $2 billion

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) runs the National Anti-Scam Centre.

ACCC deputy chair Catriona Lowe says that controlling these scams is complex and requires cooperation with local and international law enforcement and proactive work by carriers such as Meta.

“We have released a report that demonstrates an over 25 per cent decline in reported financial losses to scams during 2024, but with $2 billion lost, we still have plenty of work to do,” she said.

ACCC deputy chair Catriona Lowe says controlling these deepfake scams is complex. (ABC News)

New legislation has given the regulator the power to impose multimillion-dollar fines if platforms fail to remove scam content and these platforms are on notice.

“We anticipate that social media, including Meta, will be one of the early designated sectors,” Ms Lowe said.

“That will mean that there will be financial penalties to that sector if they do not fulfil or take reasonable steps to fulfil their obligations under that law.”

But that still leaves people like David and Janis to cope by themselves after getting scammed.

“I felt really shattered,” Janis told 7.30.

“It was horrible, because I thought this was really real. So it took me back because I had thought I’d just bought this miracle drug.”

Professor Shaw thinks the damage goes even deeper than the health and financial risks.

“What happens as a result of this and other similar things is mistrust,” he said.

” Maybe all sorts of useful things that I and other people might say about health will not be trusted. ”

Watch 7.30, Mondays to Thursdays 7:30pm on ABC iview and ABC TV

The Wegovy effect: A weight-loss drug reshapes the lives of US teens battling obesity

A small but fast-growing cohort of American teens have chosen to take Novo Nordisk’s weight-loss drug Wegovy, placing them at the forefront of a monumental shift in the treatment of childhood obesity. For these teens, obesity had become a painful physical and emotional burden, the persistent social stigma of their condition isolating them from their peers, and they were frustrated by their inability to lose weight. Some doctors, though, are hesitant to prescribe the drug, citing the lack of long-term safety data, concerns that children won’t get adequate nutrition while taking it, and the possibility that it could cause eating disorders. The overall numbers remain small – fewer than 100,000 – next to the roughly 8 million, or one in five, American teens living with obesity. Those who have embraced the treatment, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, say wegovy gives adolescents a chance at a healthier future by reducing their risk of developing type 2 diabetes, liver disease and other debilitating, and costly, chronic illnesses.

High-school freshman Austin Smith sank into depression from the merciless teasing and bullying he endured from his classmates over his weight.

By age 15, Katie Duncan felt unhealthy and self-conscious from the excessive weight she carried, but couldn’t tame the incessant food cravings caused by a tumour that had damaged part of her brain.

Ms Stephanie Serrano, diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and liver disease related to her obesity, stopped attending high school in person and became a virtual shut-in after years of failed dieting.

For these teens, obesity had become a painful physical and emotional burden, the persistent social stigma of their condition isolating them from their peers, and they were frustrated by their inability to lose weight.

That’s why, with support from their parents, they joined a small but fast-growing cohort of American teens who have chosen to take Novo Nordisk’s weight-loss drug Wegovy, placing them at the forefront of a monumental shift in the treatment of childhood obesity.

As childhood obesity rates soared in recent decades to epidemic levels, pediatricians could offer children and their families little beyond the conventional – and often ineffective – counsel of healthier diets and more exercise.

That changed in December 2022, when US regulators approved Wegovy, which has become a multibillion-dollar seller for treating obesity in adults, for children 12 and older. Since then, teenagers have been starting on Wegovy at quickly rising rates, as Reuters recently reported.

Still, based on those rates, the overall numbers remain small – fewer than 100,000 – next to the roughly 8 million, or one in five, American teens living with obesity. Those who have embraced the treatment, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, say Wegovy gives adolescents a chance at a healthier future by reducing their risk of developing type 2 diabetes, liver disease and other debilitating, and costly, chronic illnesses.

They say weight loss can also ease the harm of the teasing and social isolation teens with obesity often endure.

Some doctors, though, are hesitant to prescribe the drug, citing the lack of long-term safety data, concerns that children won’t get adequate nutrition while taking it, and the possibility that it could cause eating disorders. Their caution is echoed in statements by US Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has criticised the “overmedicalisation of our kids” and emphasises the role of healthier food in combating chronic disease.

That split leaves families to consider for themselves the potential benefits and risks of Wegovy when deciding on a course of treatment for a child with obesity. For this article, Reuters reporters found children who had taken Wegovy or a similar weight-loss drug to speak with them about their experiences. The reporters spent more than a year closely following four teens and their families to examine in detail the impact of treatment. Here are their stories:

“I can’t wait”

GLADSTONE, Missouri – “Why do you want to lose weight?”

When Ms Elizabeth Smith asked her son Austin that question, he didn’t hesitate. “To be healthier and so people will stop bullying me,” he said. Ms Smith wrote his answer on the form she was filling out as they waited in the doctor’s office.

Austin was near the end of a miserable freshman year. At almost 136 kilograms , he struggled each morning to squeeze down the aisle of the school bus. Other students teased him relentlessly. He looked pregnant, they said, and he was gross. At school, the insults continued.

He found solace in woodworking class, where he could focus on his projects and tune out the taunts – until the day a classmate cornered him, jammed a power drill into his long, curly hair and turned it on, leaving the tool dangling from a messy tangle.

Ms Elizabeth Smith tousles the hair of her son Austin Smith, who uses Wegovy for weight loss. PHOTO: REUTERS

Even before his parents learnt about that incident, they knew something was wrong. Austin, who has a mild form of autism, had grown increasingly withdrawn and rarely left his bedroom, where his mother found him sobbing after school several times. “I can’t make any friends,” Austin told her. They feared he might contemplate suicide.

They decided to seek medical help. A psychiatrist put Austin on an anti-depressant. Ms Smith thought the obesity specialist who had been treating her could help, too. Five weeks earlier, Dr Matt Lindquist at University Health in Kansas City, Missouri, near their home in suburban Gladstone, had started her on Wegovy, and she had already dropped 9kg, to around 100kg .

That’s how Austin and Ms Smith found themselves filling out forms in Dr Lindquist’s office in April 2023. Four months earlier, US regulators had approved Wegovy for teens with obesity, defined as a body mass index at or above the 95th percentile for children of the same age and sex.

The doctor judged Austin, then 15 years old, to be in good overall health and a good candidate for Wegovy. The drug would tame the constant hunger Austin described.

Dr Lindquist told Austin that after starting on Wegovy, he should cut his meal portions in half and eat more healthy proteins and vegetables. Even then, the doctor said, Austin might experience the common side effects of nausea and vomiting.

Out of pocket, the more than US$1,000 ($1,290) a month cost of Wegovy would have been unaffordable. The Smiths live pay cheque to pay cheque on Ms Smith’s pay as a hospital billing clerk at University Health and what her husband Jeremy, earns building courtroom exhibits. But Ms Smith’s employer-sponsored health insurance covered Wegovy.

About a month after the visit with Dr Lindquist, the first box of Austin’s Wegovy injections arrived. Ms Smith, fearing Austin would get sick in class, asked him to wait to start the drug until after the school year ended in a week. “I can’t wait,” Austin said. She gave him his first injection that night.

The effect was almost immediate. He used to come home from school and devour dozens of chicken nuggets while playing video games. Now, he felt full far sooner. Many nights, he stayed in his room at dinnertime. “I felt a little bad because I couldn’t eat my parents’ cooking,” Austin said. The only side effect he experienced was a little stomach upset.

Ms Smith began keeping a log of Austin’s weight. At the start of his sophomore year, two months after starting Wegovy, Austin had lost 10.5kg. That’s when he first noticed the difference: On the school bus that morning, he didn’t bump into the seats while walking down the aisle. “I was so happy to go home and tell my parents about it,” he said.

In early September 2023, Dr Lindquist increased Austin’s weekly dose of Wegovy to the maximum, 2.4 milligrams, as recommended on the label. Austin started vomiting after eating. Dr Lindquist cut the dose back to the previous 1.7 milligrams. The vomiting subsided.

Austin reveled in his altered appearance, and his mood lightened. He told Ms Smith the bullying had stopped. He liked to stand in his now billowing marching band uniform and pull the waistband outward to reveal gaping spaces.

He was back to tending his oregano, thyme and other herbs growing in pots outside the front door. He played in the backyard with his puggle, Lucy, or one of his family’s other two dogs. He spent weekends hanging out with his best friend, an elderly man in the neighbourhood, gardening, walking their dogs and watching movies.

In October 2023, five months into treatment, Austin was down to 105kg. Ms Smith wrote Dr Lindquist to ask about his target weight for Austin. The doctor responded that he didn’t set weight goals, preferring to focus on a patient’s overall health, and was encouraged by Austin’s progress. “I would say he likely needs meds lifelong to support a healthy weight,” the doctor wrote.

Ms Elizabeth’s heart sank. “I wouldn’t want him to be on this for a lifetime,” she said.

Austin didn’t share those qualms. “Before, I would look in the mirror and hate myself and wish I could be an entirely different person,” he said. “Now I feel like I can accept myself a bit more.”

He had dropped to 100.2kg by early December 2023. One Saturday, he came into the kitchen and lifted his shirt to show his family his now-visible ribs. For Christmas, Ms Smith bought him extra-large pants and shirts to replace his 2XL clothes.

“He’s like a whole new person,” his pediatrician told Ms Smith, echoing many family friends and relatives. Austin’s father was cheered by his son’s physical and emotional transformation. Jeremy had lost about 14kg while taking Ozempic, Novo’s medication for type 2 diabetes that has the same active ingredient as Wegovy.

At a January 2024 appointment, Dr Lindquist chided Austin when he admitted to skipping meals. “You need to put gas in your tank to make it go,” the doctor told him. He referred the teen to a nutritionist. Ms Smith scheduled an appointment, but had to cancel because of a work conflict and hasn’t booked a new visit. The following April, Austin was at 90.7kg . He celebrated the end of his sophomore year by taking a trip in June to Belize with other students. He snorkelled and went on eight different zip-lines through the rainforest. The weight limit for riding the zip-lines was 127kg.

Back home, Ms Smith wept when she watched the video Austin shared of him gliding through the trees. “He couldn’t have done this before,” she said.

Soon after his return, he was hit hard by the death of his elderly friend. His psychiatrist prescribed a more powerful anti-depressant. Austin then panicked when, after Dr Lindquist stretched out Austin’s dosages, he started eating more and putting on weight. That stopped when he went back to regular weekly injections.

The family got another shock in January, when Ms Smith’s insurance through University Health quit covering Wegovy and other so-called GLP-1 drugs for weight loss. Wegovy had been free, after insurance and Novo-provided coupons. Now, the health system would be providing Wegovy at US$250 for a three-month supply through its own pharmacy.

Insurance coverage for Wegovy has steadily expanded since the drug’s 2021 launch, and Novo has offered ways to bring down out-of-pocket costs. But employers and government agencies often impose restrictions to hold down costs associated with the drug’s high price and the large number of patients eligible to take it.

In 2024, 64 per cent of US employers with 20,000 or more workers covered GLP-1 drugs for obesity, up from 56 per cent in 2023, according to Mercer, a benefits consulting firm. Medicare and most state Medicaid programmes don’t cover the drugs solely for weight loss.

Ms Smith has been able to scrape together enough to cover the cost. She also had to find Austin another doctor at University Health after Dr Lindquist left to set up his own practice and the hospital stopped covering Wegovy for doctors outside of its network.

Austin is just relieved that his parents can afford to keep his prescription going. His weight has levelled off at about 91kg – a 30 per cent loss in two years. He doesn’t want to contemplate life without Wegovy. “I feel I would be bigger,” he said. “I don’t want to go back.”

“What I’m doing isn’t working”

WILMINGTON, Delaware – At 15, Katie Duncan, at 1.85m and 122kg, was growing increasingly anxious and depressed about her weight.

Some of her clothes no longer fit, she was easily winded while walking, and her back ached. Classmates occasionally lobbed mean comments about her size. Blood tests showed she had high triglyceride levels, which can increase the risk of stroke and heart disease.

But Katie’s hunger never let up. She often ate four or five meals a day. She would devour an entire pizza and hide snacks in her bedroom to satisfy cravings. She had tried an older weight-loss drug that did nothing.

“We need to change something,” she told her father, Randy, in the summer of 2023. “What I’m doing isn’t working.”

Katie Duncan uses Wegovy for weight loss. PHOTO: REUTERS

Randy scheduled an appointment at the Healthy Weight and Wellness Clinic at the nearby Nemours Children’s Hospital. The Duncans knew the hospital well: Katie had been treated there after she was diagnosed at age seven with a brain tumour.

Doctors had given her a 20 per cent chance of surviving the cancer. Katie took an experimental drug and underwent months of chemotherapy and radiation. She was tiny at the time, only 19kg. The cancer went into remission within a year.

However, the tumor had damaged her hypothalamus, the portion of the brain that controls hunger, and the nearby pituitary gland, which releases hormones that regulate growth and metabolism, among other key functions. Her doctors put her on a lifelong regimen of synthetic hormones and a low-dose steroid to replace what she lost.

The brush with death forged a fierce bond between father, divorced since Katie was three, and daughter, the youngest of five siblings and the only one still living at home. Randy, a paramedic and volunteer firefighter, took off from work to go to every doctor’s appointment and physical therapy session with her. Katie treasured a locket with her father’s photo inside and refused to go to school without it. He accompanied her on every school field trip. Katie tried a sleep-away camp hosted by the hospital and called her dad to pick her up after the first night.

“I don’t like being away from my family,” she said.

But by the time Katie was nine , Randy, now remarried, noticed something was wrong. Katie was constantly hungry, and the two clashed repeatedly over it. During a trip to SeaWorld in Florida, they shouted at each other when Katie complained that she was starving, even after a big breakfast at their hotel.

Katie steadily put on weight during her middle-school years. She avoided running and other sports due to painful neuropathy in her feet, likely caused by her cancer and chemotherapy. She couldn’t keep pace with classmates in physical education.

At her appointment in 2023, Katie saw Dr Thao-Ly Phan, medical director of the Nemours weight clinic. After examining Katie and reviewing her medical history, Dr Phan determined that Katie probably has “hypothalamic obesity” from her brain injury, for which the replacement hormones don’t fully compensate. “Her body isn’t helping her out,” Dr Phan said.

While brain cancer isn’t common, Dr Phan said, teens can have other, more common underlying conditions or treatments that lead to obesity and complicate their care. For example, polycystic ovary syndrome can cause hormonal imbalances and weight gain, especially around the belly, in young women. Antidepressants, mood stabilisers and other psychiatric medications can lead to weight gain, too.

After prescribing Wegovy, Dr Phan had Katie see the clinic’s psychologist and nutritionist, a routine step the doctor requires of her patients. “We don’t want kids to lose so much weight that they develop eating disorders,” she said. “We want to make sure that they’re still getting the nutrition they need to grow and to thrive.”

Katie got her first dose of Wegovy in November 2023. She lost about 9kg in the first couple months, with only mild side effects.

At times, Katie had no interest in eating and skipped meals, despite Dr Phan’s warnings not to. Poor nutrition and eating habits during adolescence can have long-term consequences, from impairing cognitive development to increasing the risk of osteoporosis and bone fractures, research shows.

About six months after Katie started treatment, the family’s insurer cut off coverage of her Wegovy. Randy’s appeal of that decision failed, and he switched Katie’s prescription to her secondary insurance with the state Medicaid programme, which had been in place since her cancer treatment. Delaware is one of 14 states with Medicaid coverage for the newer GLP-1 weight-loss drugs. Katie missed only one weekly dose.

At an appointment with Dr Phan in March, Katie weighed 95kg, down 60, or 22 per cent of her body weight, in about 18 months. Her triglycerides were no longer elevated.

The weight loss has brought welcome changes. Katie said she used to lack motivation to do much at all and would lounge for hours in bed. “I used to always feel yucky before,” she said. “The weight loss has actually helped a lot with my energy.”

The 17-year-old now enjoys regular visits to the Planet Fitness gym with her father and stepmother, Denise, and spends more time on her painting and crafts. She has more stamina to cook two hours straight in her high-school culinary class. She also doesn’t get winded chasing after her two-year-old niece at family gatherings. While she used to hide herself in baggy clothes, she now feels comfortable wearing sundresses.

Randy is pleased with Katie’s progress. He worries that Delaware may stop covering GLP-1 weight-loss drugs through Medicaid due to budget shortfalls or proposed cuts in federal funding. California and North Carolina are seeking to rescind Medicaid coverage of the drugs to save millions of dollars. “I hope to God they keep Wegovy around for kids,” Randy said.

Katie wants to stay on the drug and trusts that her dad and her doctor wouldn’t let her take anything harmful. “Wegovy doesn’t scare me,” she said. “I’ve had so many needles in my life.”

“I’ll do whatever it takes”

DODGE COUNTY, Wisconsin – Early in 2024, after eight months on Wegovy, Leo had a choice to make. He could stop taking the drug, end the side effects that were wreaking havoc on his life and risk regaining some of the more than 11kg h e had lost. Or he could stay on it, keep losing weight and hope the severe stomach aches, nausea and diarrhea would abate.

For this article, Leo and his mother Jamie asked Reuters to withhold details such as their precise location and Leo’s surname, and Leo declined to be photographed. They said they feared the exposure would lead to more teasing from Leo’s peers about his appearance and his decision to take a weight-loss drug.

Leo had been a strong candidate for Wegovy when he first saw an obesity specialist, Dr Leslie Golden, in mid-2023.

He was a compulsive eater from an early age, due in part to his attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, for which he takes medication. He was diagnosed with obesity at 11 years old. Three years later, he was carrying 82kg on his 1.6m frame.

Jamie tried to stock the kitchen with healthier foods. But Leo’s older sister and two older stepbrothers wanted ultra-processed snacks and sugary drinks around. Leo would gulp down five cans of Coke in a day. He sneaked snacks and sodas into his bedroom at night, leaving empty wrappers and cans for his mother to find strewn about the next morning. One of his stepbrothers was severely underweight, complicating Jamie’s food choices for the family.

The teasing and bullying started in middle school. When he walked the halls between classes, other students hurled jeers and jokes at him. “It was always directed at my weight,” he said. “The comments just got to me.”

Leo knew he had a problem but felt powerless to do anything about it. “I was eating way too much,” he said. “I was worried I was going to get way too overweight.” Jamie, a pharmacist, thought Wegovy might help. Frustrated with her own efforts to lose weight, she had started taking the drug in January 2022. She, like Leo after her, suffered severe gastrointestinal side effects, but they faded, and after a year, she had lost 23kg. Leo, having learnt what Wegovy did for his mother, was open to trying it.

In June 2023, Leo had his first appointment with Dr Golden, at her obesity clinic in a town near where he and his family live about an hour outside Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He already bore troubling signs of the effects of his obesity. His blood pressure was high. His elevated blood sugar level put him at increased risk for type 2 diabetes. The doctor worried that Leo could develop liver and heart disease if he didn’t lose weight. She prescribed Wegovy.

Dr Golden doesn’t require families to undergo counseling on lifestyle changes as a prerequisite for prescribing the drug for children. She said most families have already tried other ways to lose weight before they reach her office, and imposing a months-long delay before drug therapy “is really just another form of bias and stigma”.

She does ask for monthly visits so she can monitor a child’s progress. Her patients pick three goals for the coming month – for nutrition, movement and behavior. For Leo, at one point, that meant eating more carrots and cauliflower, playing basketball in the driveway and downing fewer sugary drinks.

Soon, Leo was eating a lot less, though what he ate didn’t change so much. At restaurants, he could stomach only three bites of the double cheeseburgers he usually ordered.

He was happy with the weight he was losing. The bullying was easing up, and some classmates even complimented him on looking thinner. He grew comfortable raising his hand in class. “It feels pretty good to get myself out there,” he said. But as his doses steadily increased – the standard of care for GLP-1 medicines is to up the dose every four weeks – the side effects started taking a toll. He took medicines to quell the nausea and diarrhea. He dropped off anti-diarrhea pills with the school nurse. Some days, his stomach upset was so bad that Jamie had to pick him up at lunchtime.

Leo was experiencing by far the most common side effects of Wegovy. In the largest clinical trial of the medicine on teens, 62 per cent of patients experienced nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Most reported mild to moderate side effects that lasted two to three days. Since their launch, Wegovy and other GLP-1 drugs have also been associated with much rarer incidents of gastric paralysis, pancreatitis, depression and blindness.

As his absences piled up, Leo’s grades suffered, and he grew moodier. At a parent-teacher conference in October 2023, teachers told Jamie that Leo had become more withdrawn in class. At a check-up with his regular pediatrician later that month, his answers on a questionnaire indicated depression. The doctor prescribed an antidepressant.

That didn’t lessen the side effects, though, and Leo’s school absences persisted. In February 2024, the high school notified his mother that he had missed 10 days, the maximum allowed for the year. Soon after that is when Dr Golden presented Leo with the choice about continuing with Wegovy. Jamie favoured sticking with the drug. The doctor wanted the choice to be Leo’s. “Jamie is a very involved parent who wants to protect and do what’s best for him,” Dr Golden later told Reuters. “I had to really zone in on Leo: Do you want to keep taking this?”

Despite the physical pain and discomfort, the problems at school, the depression, Leo was adamant. “I’ll do whatever it takes,” Leo told Dr Golden. “No matter how sick I get, I don’t want to stop.”

Several weeks later, the side effects began to ease. By last summer, Leo had dropped under 68kg. His waist had shrunk by 12.7cm . Based on his body mass index, he no longer had obesity.

“I am happy that I don’t get called names anymore,” Leo said.

Then last autumn, he started to put on weight. Dr Golden had reminded Leo that some additional weight was expected as he grew 7.6cm taller over the span of a year. But Leo’s mother found food wrappers and soda cans in his bedroom. In November 2024, Leo wept when he stepped on the scale at home and saw that he had gained 6.3kg . “I’m getting fat again,” he told his mother.

At an appointment with Dr Golden the following month, the doctor put Leo on the highest weekly dose of Wegovy to help counter his cravings.

That worked, without the side effects he had experienced earlier. At a check-up in April, Leo weighed 70kg, down nearly 14kg in the past two years.

Leo took a cooking class during his sophomore year and hopes to attend culinary school one day. He also took a part-time job stocking shelves at the local hardware store.

Leo’s pediatrician was pleased with his improved self-esteem and energy level. She asked Jamie: “What is the end game? When is Dr Golden going to stop it?”

That’s an open question. Dr Golden has repeatedly advised Leo that he will probably have to take Wegovy for the rest of his life to maintain a healthy weight. Leo and his mother are OK with that. “There is no end game,” Jamie told the pediatrician.

Afraid of gaining it back

FREDERICK, Maryland – Stephanie Serrano didn’t want to take a weight-loss drug. She didn’t think it would work, and even if it did, she didn’t like injections, especially if she had to get them for the rest of her life.

But Stephanie was desperate. At 145kg, she had already been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and liver disease. She was tired of being the biggest kid in class and had become a virtual shut-in after years of failed dieting. “Every doctor that I had ever seen would just tell me to eat healthier, like it was that simple,” Ms Stephanie said.

In 2022, her family doctor referred the then-16-year-old to the obesity clinic at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, DC. There, initial tests revealed that she had polycystic ovary syndrome, a common cause of weight gain in young women. “That diagnosis changed everything,” she said. “I wasn’t lazy or not trying hard enough. My body was actually working against me.”

In October that year, Stephanie’s doctor at Children’s National, Dr Susma Vaidya, prescribed Ozempic, Novo’s drug for type 2 diabetes with the same active ingredient as Wegovy, which hadn’t yet been approved for teens. Ozempic has been widely used off-label for weight loss, both prior to Wegovy’s launch and after due to shortages and spotty insurance coverage of the latter.

By the time she saw Dr Vaidya, Stephanie had her heart set on weight-loss surgery, swayed by TikTok videos of young adults showing their dramatic before-and-after transformations. “Seeing how much they changed, it’s incredible,” she said. “So that’s kind of what I wanted for my life. I wanted a permanent change.”

Stephanie Serrano lost weight by using Ozempic and undergoing bariatric surgery. PHOTO: REUTERS

Dr Vaidya, medical director of the obesity clinic at Children’s National, persuaded Stephanie to accept a compromise: Stephanie would give Ozempic a try while undergoing a six-month evaluation, including sessions with a dietician and a psychologist, to determine whether she was a good candidate for surgery, based on factors like adequate family support and eating regular, well-balanced meals.

Stephanie started taking the lowest recommended dose of Ozempic. The side effects were mild, though she occasionally experienced nausea and stomach pain after a big meal. She lost 4kg in the first month. After four months, in February 2023, she was surprised – and pleased – that she had lost about 14kg.

“I had never seen the number on the scale go down,” she said. At that point, Dr Vaidya told Stephanie she could continue taking the drug, or she could undergo surgery. Stephanie’s father, Jose, who was taking Ozempic for his type 2 diabetes, preferred that she stick with the drug. He worried about her risk of complications from a major operation.

Stephanie held firm. Despite her weight loss on Ozempic, she felt that surgery was the only way to end the isolation she had endured for years.

Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, Stephanie had retreated from school and friends. In 2021, during her sophomore year, her high school gave students the option to return or continue with online classes. She never went back to the classroom.

Through the lens of social media, she watched classmates gloat about their beauty “glow ups” and post photos of themselves with new makeup routines and outfits. Stephanie quit the school’s Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, a leadership programme sponsored by the US military, to avoid being around other people.

“I hid myself for those years,” she said. “I no longer wanted to be a prisoner.”

In April 2023, Stephanie, at about 129kg, had gastric-sleeve surgery, which involved removing a large portion of her stomach to reduce food intake. She came through the surgery and recovery without complications. Today, the 19-year-old college freshman is down to about 79kg. She eats small meals and exercises regularly. Her diabetes is in remission, and her liver function is normal. She takes a full load of classes at a nearby community college and plans to transfer to a four-year university soon. She aspires to be a sports psychologist.

As Stephanie lost weight, she became more outgoing at school and in church and found she could make friends. She opened up to the possibility of a relationship and flirted with a young man at church. That didn’t go anywhere, but she had surprised herself with her willingness to even try. “Having a crush on anyone seemed so silly before. I could never imagine someone loving me,” she said. “I was always ashamed of myself.”

Amid all this progress, another problem emerged: Ms Stephanie was consumed with fear of gaining the weight back.

She started skipping meals and guzzling energy drinks. After eating a small meal, she would run a mile to burn off the calories. Her legs and back began to ache, and she sometimes lost her balance – signs of possible muscle loss. Dr Vaidya told her, “This is your body asking for protein.”

Dr Vaidya diagnosed Ms Stephanie with an eating disorder in April 2024 and referred her to a hospital psychologist. Dr Vaidya also prescribed bupropion, an anti-depressant sometimes used to manage binge eating. The possibility that weight-loss drugs may put teens at risk of disordered eating is why some doctors urge rigorous screening of patients and continuous monitoring during treatment. Research on any association between weight-loss drugs or bariatric surgery and eating disorders is limited. Some small studies found that the use of GLP-1 drugs may decrease binge eating episodes among those who already had the disorder. But the studies only tracked patients for three to six months, leaving longer-term effects unknown.

Ms Stephanie’s psychologist urged her to stop counting calories and poring over the nutrition labels on packaged foods. She’s making progress, but it’s a “constant battle,” she said. Stephanie still gives in sometimes to count calories, and when she exceeds her target, “I completely shut down.”

At home, Ms Stephanie does much of the cooking for her parents and older sister, Lily. She rarely eats what she cooks. At a recent dinner, her family enjoyed the carne asada, beans and pico de gallo she had prepared while she picked at a small bowl of rice and a homemade tortilla. She didn’t finish either.

Later, Ms Stephanie, her mother, Ms Vanessa Serrano, and Lily visited a local mall – a place she used to avoid because it was hard to find clothes her size there. At the American Eagle store, she tried on a pair of black jeans. She emerged hesitantly from the dressing room to have a look in a mirror. After Lily told her she looked incredible and snapped photos, Ms Stephanie checked herself out from several angles. She bought the jeans and wore them to church the next day. REUTERS

Join ST’s Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

Here’s How and Where to Get Wegovy Online in 2025

Ro is a telehealth platform specializing in sexual health, fertility, hair, skin, and general wellness. The company also offers The Body Program — a weight loss program that pairs on-demand virtual medical visits with weight tracking and prescriptions for weight loss medications, including Wegovy.

The company also offers The Body Program — a weight loss program that pairs on-demand virtual medical visits with weight tracking and prescriptions for weight loss medications, including Wegovy.

How it works: Ro makes it easy to get started by completing an online visit. A healthcare professional will review your visit and schedule an in-depth consultation to determine eligibility. If Wegovy or another weight loss medication is appropriate, Ro will connect you with its insurance concierge team to help navigate coverage for the medication.

Prescriptions for branded drugs, like Wegovy, are sent to a pharmacy of your choice, usually within 4 to 6 weeks after your initial visit.

Your ongoing subscription includes on-demand access to your assigned medical professional via video or text messaging, progress tracking, and refill management.

Read our full review of Ro and its services.

Insurance coverage: The Ro Body program is not covered by insurance. However, Ro can work with your insurance to determine whether GLP-1 medications may be covered.

Semaglutide: Side effects, use for weight loss, cost

Semaglutide is the active ingredient in the brand-name drugs Ozempic, Wegovy, and Rybelsus. Currently, there is no generic version of semag lutide approved by the FDA.

If you’re interested in generic alternatives to Ozempic, Wegovy, or Rybelsus, talk with your doctor. They can recommend treatments for your condition. If you have insurance, you’ll also need to check which medications are covered under your plan. You can find information about semaglutide and cost later in this article.

Learn more about how generics compare with brand-name drugs.

Video: GLP-1 Medications Revolutionize Obesity and Diabetes Care, With Exciting Advances on Horizon

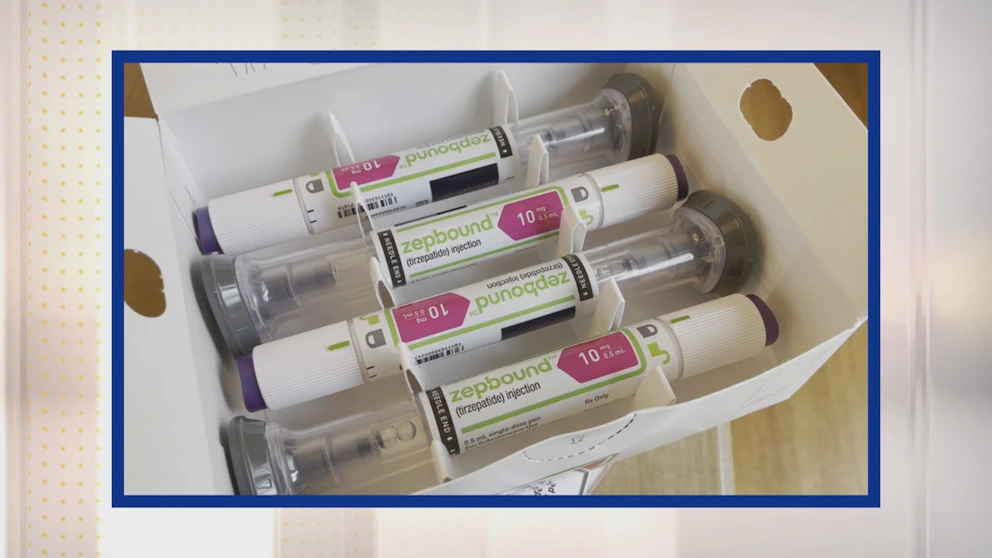

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists have dual role in diabetes and obesity treatment. Professor emerita Donna Ryan, MD, discusses the current landscape of GLP- 1 medications. Ryan provides an overview of currently approved GLp-1s on the market, including semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy; Novo Nordisk) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro; Eli Lilly) There are also drugs that can control cardiovascular risk and mitigating chronic kidney disease. The drugs have really been developed in 2 main areas: for diabetes and for obesity. The GLP1 hormone in our bodies has effects on appetite, and it also has Effects on Blood Glucagon (Glycogen) The drugs that are available that produce a lot of weight loss for people with obesity are WegovY and Zepbound (Wegovy, Zep bound) For diabetes, the same molecules are out there as Ozempic and Moun Jaro.

Closed captions for this video were auto-generated by artificial intelligence.

Pharmacy Times: Could you provide a brief overview of the current landscape of GLP-1 medications?

Donna Ryan, MD: You know, everybody thinks the GLP-1 medications are brand new and ultra exciting. Well, they are ultra exciting. But let me tell you: we’ve had GLP-1 medications around for 20 years. In fact, the first one was approved for diabetes in 2005; that was exenatide (Byetta; Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly). The first one was approved for obesity in 2014; that was liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda; Novo Nordisk). So, these are medications we’ve known for a long time. But native GLP-1, the hormone in our bodies, has effects on appetite, and it also has effects on controlling blood glucose. When your blood glucose level is high, it promotes the secretion of insulin and lowers it. The drugs have really been developed in 2 main areas: for diabetes and for obesity. But look: nobody got interested in this until about 2022, when semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy; Novo Nordisk) came out. Semaglutide had been around a few years for diabetes, as Ozempic, and it was approved as Wegovy for obesity. The data in people who don’t have diabetes show that the weight loss was around 15% to 17%, much higher than we had gotten in prior obesity medications. This is an average weight loss of 15 to 17%. Then, tirzepatide (Zepbound, Mounjaro; Eli Lilly) came out. This is both a GLP-1 and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist. So, it’s hitting the receptors for 2 of those gut hormones. What’s important about that one is that it was associated with a weight loss average of 22.5%. This double-digit weight loss really got the public interested, but it’s the doctors, I think, that really became interested in 2023 when the SELECT trial came out. It showed that this medication could prevent the second heart attack, stroke, or sudden death in people who had established cardiovascular disease. That’s called a secondary prevention trial, and we had never seen anything like that before with our medications for obesity, so it really was quite a big deal. It’s a combination of both the amount of weight loss that patients appreciate and the effect on disease modification, the prevention of cardiovascular disease, that really has everyone so excited.

Right now, the drugs that are available that produce a lot of weight loss for people with obesity are Wegovy—that’s semaglutide—and Zepbound—that is tirzepatide. For diabetes, the same molecules are out there as Ozempic and Mounjaro. A little confusing, but believe me, just 2 molecules are good for both diabetes and weight management. So that’s what we have available. There are still the other older GLP-1 medications. They don’t produce as much weight loss, and they don’t produce as much glycemic control, so people are less interested in them, but they’re still good medications.

Pharmacy Times: Are there any new, expected study data or approved indications on the horizon or in development?

Ryan: First of all, let’s go over some recent discoveries. You know, I think the disease-modifying discoveries are the ones that have really captured people’s attention. So tirzepatide has a label indication now for obstructive sleep apnea—it really has a huge impact. It reduces the apnea-hypopnea events that occur in people who have obesity-related obstructive sleep apnea. So that’s big news. But we’re also seeing clinical trial data come out that these medications are showing efficacy in heart failure (HF), HF with preserved ejection fraction especially, and in prevention of progression of kidney disease. Then there are lots of clinical trials underway; we don’t have data yet, but clinical trials are underway looking at if these drugs may have potential for neuroinflammation. So, things like Parkinson disease (PD) or Alzheimer disease (AD) or dementia; that would be very exciting. There’s even an interest in these drugs as potential uses for smoking cessation and for addiction disorders. There are lots of things that we don’t know about yet but that are garnering a lot of attention.

I guess everyone is also really excited about the future of this class. What we’re doing is we are adding agents to that GLP-1 backbone. It’s not really a structural backbone. It’s just the idea that we have so many positive attributes with GLP-1; well, if we add this compound to it, we could get even greater efficacy. There are 2 big studies that are out there that everyone is very interested in, and that is the combination of semaglutide with a long-acting amylin; that is called CagriSema. We’re expecting the phase 3 results to come out on that any day—very excited about that. And then the other, there’s what’s called a single molecule triple agonist. You know, tirzepatide was GLP-1 and GIP. Well, this molecule has three: GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon. It’s called a triple agonist, and it’s also in phase 3. We want to see those results because the phase 2 data make us expect that it’s going to produce average weight loss in the high 20s. Those would be very powerful medications. We want to see what’s going to happen there.

Source: https://abcnews.go.com/GMA/Wellness/video/weight-loss-medication-heart-health-123068181