When the government pushed, and a newsroom pushed back

How did your country report this? Share your view in the comments.

Diverging Reports Breakdown

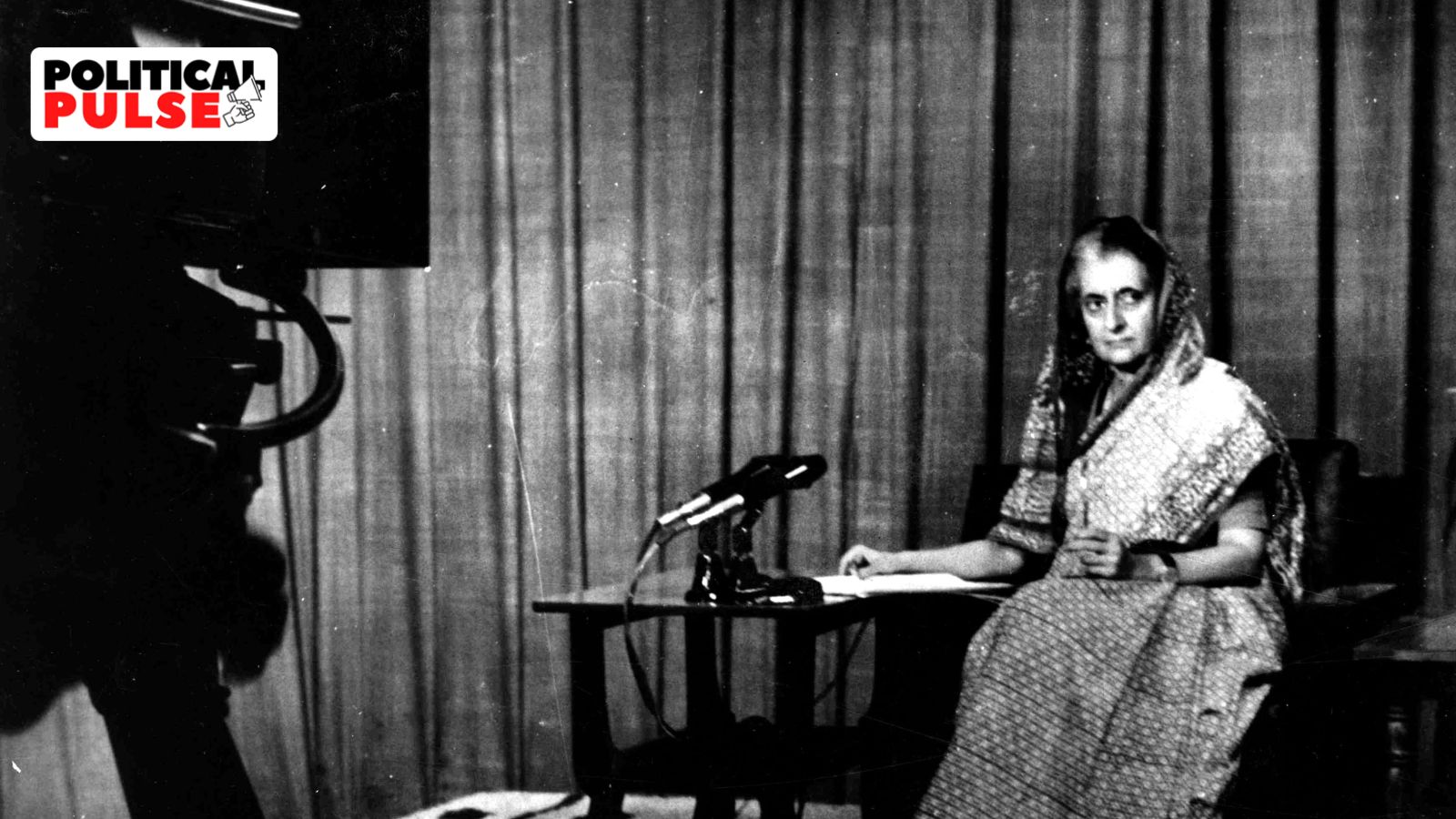

The Emergency, 50 years on: When the government pushed, and a newsroom pushed back

The Indian Express was one of the first newspapers to come out after the Emergency was declared in 1975. Editor Kuldip Nayar advised reporters to make daily notes for posterity, even if the censors would not permit us to write of the travesty of democracy we were witnessing first hand. Nayar refused even when newly appointed Information and Broadcasting Minister Vidya Charan Shukla threatened him. The Express was already perceived as an opponent of the government given its support to the JP Movement. The authorities did not take this kindly, particularly as the Express was. perceived to be an opponent to the government. The Indian Express is now owned by the Ramnath Goenka family, who have a son Bhagwandas and a daughter-in-law, both of whom were arrested during the Emergency. The family has since moved to a new home in a suburb of the capital, New Delhi, which they have named after their late father and mother. They have also started a new life as a business couple.

On June 26, around 4 am, I was woken by a phone call from my sister Roxna informing me that Jayaprakash Narayan, known universally as JP, and many other Opposition leaders had been arrested. Jana Sangh leader Nanaji Deshmukh, who had managed to escape thanks to a tip-off, had alerted Roxna’s husband Subramanian Swamy to leave the house. My husband Virendra Kapoor, also a journalist, rushed to the UNI news agency office next door to get the latest information and the names of those arrested. Hours later, Roxna rang again to tell me to switch on the radio; Indira Gandhi had imposed an internal Emergency.

Advertisement

I telephoned my chief reporter, Abdul Rehman, requesting that the battered Indian Express van be sent so that I could visit the homes of the detained leaders for a report. The seasoned Rehman was cautious, warning that we wait till we knew the government’s intentions. That morning, The Indian Express, like many other newspapers, had not come out as the electricity supply to the printing presses had been cut just as the paper went to bed.

Early afternoon, when I reached The Indian Express office, an unforgettable sight awaited me. The reclusive, slightly haughty editor-in-chief Srikrishna Mulgaokar, who seldom mingled with the staff, was sitting in the middle of the newsroom, his hand on his forehead, reading the teleprinter news dispatches being handed to him deferentially by News Editor Piloo Saxena. Soon, there was a news flash announcing that censorship was in force and nothing could be printed without prior clearance of the authorities. To make doubly sure that the Express was silenced, electricity was once again disrupted that night.

On June 28, when the newspaper finally came out for the first time after the Emergency was declared, it carried a blank editorial as a protest. The authorities did not take this kindly, particularly as the Express was already perceived as an opponent of the government given its support to the JP Movement.

Story continues below this ad

Meeting of Opposition leaders Jai Prakash Narayan, Raj Narain, Morarji Desai and LK Advani during the Emergency 1975. (Express Archive) Meeting of Opposition leaders Jai Prakash Narayan, Raj Narain, Morarji Desai and LK Advani during the Emergency 1975. (Express Archive)

Nayar, head of the Express News Service, asked us reporters to be present the next day at the Press Club along with likeminded colleagues from other newspapers to sign a petition against censorship and the arrest of journalists. The younger scribes were enthusiastic about putting their names on the letter addressed to the Prime Minister, but some cynical senior correspondents stayed away. We learnt later that an informer from among us had alerted the authorities. Nayar forwarded the letter, but not the names of the signatories. He refused even when newly appointed Information and Broadcasting Minister Vidya Charan Shukla threatened him. Shortly afterwards, we heard that Nayar was in jail, detained under the dreaded MISA (Maintenance of Internal Security Act).

Prison soon became a familiar destination in my circle. Senior reporter B M Sinha was jailed for being a member of the Ananda Marga. My husband, who worked for The Financial Express, was arrested under MISA following an altercation with Youth Congress leader Ambika Soni over manhandling of protesting youths. Our friend Prof Suresh Upadhyay, one of the leaders of the IIT, Delhi, union, was picked up from a railway platform. Kirit Bhatt, the Express’s Baroda correspondent, was charged with being a co-conspirator in the Baroda Dynamite case involving George Fernandes. A number of Delhi University student leaders, including Arun Jaitley, and local politicians whom I knew well were also taken into custody.

V C Shukla was determined to take control of The Indian Express. But owner Ramnath Goenka, always addressed by the staff as RNG, was a tough nut to crack. Shukla had the Company Affairs and Law Ministries examine the Express’s financial records with a tooth comb. He even threatened to arrest RNG’s son Bhagwandas Goenka and his wife Saroj under MISA. The Income Tax department claimed Rs 4 crore as back taxes. The newspaper’s finances were in such a bad way that salaries were delayed and paid in instalments. The staff went to Mulgaokar to complain. His response: “Do you think I have money in my pockets that I can pay you?” We retreated sheepishly.

As the government pulled out all its artillery, RNG agreed to a formula where the government formed a board to run the Express, with Hindustan Times owner K K Birla as chairperson, and a majority of the members selected by the government. In March 1976, RNG suffered a heart attack and the board, in his absence, removed Mulgaokar as Editor. V K Narasimhan, the seemingly mild-mannered Editor of The Financial Express, was asked to take temporary charge.

Narasimhan, however, proved to be no pushover. He refused to transfer Deputy Editor Ajit Bhattacharjea and Nayar, by then out of jail, to Gangtok and Kohima, in faraway Northeast, respectively. Bhattacharjea had infuriated the government by writing an article critical of the Supreme Court order saying the right to seek redressal for illegal detention (habeas corpus) could be suspended. The edit pages were better positioned for occasional criticism, and articles with subtle and not-so subtle references to the Emergency rule. On the news pages, it was more difficult to do so, but we managed to occasionally slip in an innuendo or two in which a discerning reader could join the dots.

The government thought an ailing RNG would not be able to attend the annual general meeting of the Express board held in 1976, but this was a miscalculation. RNG turned up, gave Birla a tongue-lashing, and dismissed the thunder-struck board. He cited the violation of a rule that the names of government directors and chairperson had to be ratified by shareholders within a stipulated period.

The government did not take kindly to being outwitted. Pre-censorship was imposed on the newspaper again, and this meant that printing was delayed and the newspaper could not reach hawkers in time for morning distribution. The Express challenged the pre-censorship in court. All government and PSU advertisements were withdrawn from the newspaper and pressure was also put on private advertisers. When the monopoly nationalised news agency Samachar cut off its services, two staffers, Jawid Laiq and Bharati Bhargava, were assigned the task of monitoring AIR and foreign news bulletins on RNG’s antiquated radio.

We employees lived in constant trepidation of the newspaper’s closure. Nevertheless, there was a comforting sense of camaraderie within the office, which was absent in the outside world where many former friends now kept their distance fearing reprisal from the authorities as we were seen as marked people.

Also Read | How Indira Gandhi used the Constitution to subvert democracy

In October, officials from the Municipal Corporation of Delhi, accompanied by a large posse of police personnel, forcibly seized and sealed the printing press located in the Express building basement. I was convinced that this was the end game. But, I had not reckoned with RNG’s gutsy spirit. The Express legal team, advised by the equally feisty Fali Nariman, produced a rabbit out of the hat – a stay order from the Delhi High Court, on the grounds that the arrears of payment that were cited for the sealing were in dispute and the property was owned by one of RNG’s southern companies and not The Indian Express, Delhi.

The intimidation continued. Banks refused to advance money for the purchase of newsprint. Official agencies lodged some 320 cases all over India against RNG. None of the magistrates would grant the newspaper owner an exemption from personal appearance. RNG vowed to Nariman, “I will never compromise.’’ At some point, however, with the newspaper starved of funds, RNG realised that it was perhaps wiser to retreat temporarily so that he could live to fight another day. He explored the option of hiring Khushwant Singh, a known Gandhi family favourite, as Editor and even made a verbal offer through Nayar, who was Singh’s student at Lahore Law College

Fortunately within days, Nayar, with his reporter’s unerring nose for news, sniffed out the most sensational scoop of the Emergency. Indira Gandhi planned to hold elections by March 1977. RNG and Nayar knew their necks were on the line if the report proved false. The next day, the Press Information Bureau verbally warned the newspaper for its “false” report. But news of the Express story spread like wild fire, and was the only talking point in jails across the country. Two days later, Mrs Gandhi herself announced that she was calling elections.

After her announcement, though censorship rules remained officially in place, the Express went all guns blazing exposing the numerous Emergency excesses – the mass arrests, the pathetic condition of some of the families of MISA detainees, the demolitions of slums ordered by Sanjay Gandhi and the ruthless sterilisation drives, particularly in villages of Pipli and Uttawar where protesting villagers were mowed down by police bullets.

Whenever I went to cover an Opposition rally, I was greeted with warmth bordering on reverence when I mentioned I was from The Indian Express. Colleagues from rival newspapers, which still kept silent, found themselves at the receiving end of the public’s ire. The circulation of the Express soared.

In the elections held in March 1977, I opted to cover the East Delhi Lok Sabha constituency, the Capital’s poorest and a Congress bastion represented by party strongman H K L Bhagat. I walked up and down the new resettlement colonies of East Delhi and the narrow lanes of Shahdara. I concluded, a little nervously, that the Congress seemed set to lose all the six Delhi parliamentary seats. But I pessimistically assumed that the Iron Lady with her larger-than-life image would win nationally. Else, why would she call the elections?

On D-Day, March 20, I was at the Shahdara counting centre for the East Delhi constituency. When the wax seals of the ballot boxes were finally broken, the suspense was short-lived. The results were obvious even before the counting started. The piles of ballot papers for the Janata Party were more than double those for the Congress.

I rushed back to the office to file the trends of Delhi’s results for the paper’s Dak edition. Back in the newsroom, I learnt that the overall national picture was still unclear. It appeared there was a North-South divide. Samachar was reporting mainly Congress victories from southern states and was suspiciously silent on the position in the North and West.

As I was typing my copy, I suddenly heard shouts and screams emanating from the semi-circular copy desk where the sub-editors sat. The whole newsroom was abuzz with excitement and, for some moments, work came to a standstill. Our correspondent from Lucknow had telephoned to inform that the seemingly invincible Mrs Gandhi was trailing from Rae Bareli. At that moment I realised that the future was full of promise. If Indira Gandhi was losing her own seat, it was unlikely that her party people would survive.

The nightmare of the Emergency would finally be over.

Kapoor is a Contributing Editor with The Indian Express, who was a reporter with the newspaper throughout the Emergency. She is the author of the book The Emergency